http://www.wesjones.com/kesey.htmThe Prince of Possibility*

Robert Stone**When Ken Kesey seemed capable of making anything happen.In a cabin in 1964, Ken Kesey was working in so deep in the redwoods south of San Francisco that its indifferently painted interior walls seemed to grow seaweed instead of mold. Despite its glass doors, the cabin held the winter light for little more than a midday hour, and the place had the cast of an old-fashioned ale bottle. It smelled of ale, too, or, at least, of beer, and dope. Those were the days of seeded marijuana: castaway seeds sprouted in the spongy rot of what had been the carpet, and plants thrived in the lamplight and the green air. Witchy fingers of morning-glory vine wound through every shelf and corner of that cabin like illuminations in some hoary manuscript.

Across the highway, on the far bank of La Honda Creek, there were more morning-glory vines. They were there, Kesey said, because he had filled the magazines of his shotgun with morning-glory seeds and fired them into the hillside. The morning glory, as few then understood, is a close relative of the magical ololiuqui vine, which was said to be used by Chibcha shamans in necromancy and augury. Once ingested, the morning glory's poisonous-tasting seeds produced hours of startling visions and insights. The commercial distributors of the seeds, officially unaware of this, gave the varieties names like Heavenly Blue and Pearly Gates. (A warning: Don't try this at home! The morning-glory seeds sold these days are advertised as being toxic to the point of deadliness.)

La Honda was a strange place, a spot on the road that descended from the western slope of the Santa Cruz Mountains toward the artichoke fields on the coast. Situated mostly within the redwood forest, it had the quality of a raw Northwestern logging town, transported to suburban San Francisco. In spirit, it was a world away from the woodsy gentility of the other Peninsula towns nearby. Its winters were like Seattle's, and its summers pretty much the same. Kesey and his wife, Faye, had moved there in 1963, after their house on Perry Lane, in Menlo Park, was torn down by developers. Perry Lane was one of the small leafy streets that meandered around the Stanford campus then, lined with inexpensive bungalows and inhabited by junior faculty and graduate students. (The Keseys had lived there while Ken did his graduate work at the university and afterward.) The area had a bohemian tradition that extended back to the time of the economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen, who lived there at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Kesey, as master of the revels sixty years later, did a great deal to advance that tradition. There were stoned poetry readings and lion hunts in the midnight-dark on the golf course, where chanting hunters danced to bogus veldt rhythms pounded out on kitchenware. One party on Perry Lane involved the construction of a human cat's cradle. Drugs played a role, including the then legal LSD and other substances in experimental use at the V.A. hospital in Menlo Park, where Ken worked as an orderly. The night before the houses on the lane were to be demolished, the residents threw a demented block party at which they trashed one another's houses with sledgehammers and axes in weird psychedelic light. Terrified townies watched from the shadows.

I first met Kesey at one of his world-historical tableaux- a reenactment of. the battle of Lake Peipus with broom lances and saucepan helmets. (The Keseys' kitchenware often took a beating in those days, though I can't say I remember ever eating much on Perry Lane.) I was a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford's Writing Program and a Teutonic Knight. Ken, who was Alexander Nevsky, was working on his second novel, "Sometimes a Great Notion."

When the Keseys moved to La Honda, it became necessary to drive about fifteen miles up the hill to see them. Somehow the sun-starved, fern-and-moss-covered quality of their new place affected the mood of the partying. There was the main house, where Ken and Faye lived with their three children, Shannon, Zane, and Jed, and several outbuildings, including the studio cabin where Kesey worked. There were also several acres of dark redwood, which Kesey and his friends transformed little by little, placing sculptures and stringing batteries of colored lights. Speakers broadcast Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Ravi Shankar, and the late Beethoven quartets. The house in the redwoods increasingly became a kind of auxiliary residence, clubhouse, cookout- a semi-permanent encampment of people passing through, sleeping off the previous night's party, hoping for more of whatever there had been or might be. It was a halfway house on the edge of possibility, or so it appeared at the time. Between novels, Ken had forged a cadre in search of itself the core of which- in addition to Kesey's close friend Ken Babbs, who had just returned from Vietnam, where he had flown a helicopter as one of the few thousand uniformed Americans there- consisted at first of people who had lived in a school on or near Perry Lane. Many of them had some connection with Stanford. Others were friends from Ken's youth in Oregon. Old beatniks, like Neal Cassady, the model for Jack Kerouac's Dean Moriarty, in "On the Road," also came around. Some of the locals, less used to deconstructed living than the academic sophisticates in the valley below, saw and heard things that troubled them. As the poet wrote, it was good to be alive and to be young was even better.

More than the inhabitants of any other decade before us, we believed ourselves in a time of our own making. The dim winter day in 1964 when I first drove up to the La Honda house, truant from my attempts at writing a novel, I knew that the future lay before us and I was certain that we owned it. When Kesey came out, we sat on the little bridge over the creek in the last of the light and smoked what was left of the day's clean weed. Ken said something runic about books never being finished and tales remaining forever untold, a Keseyesque ramble for fiddle and banjo, and I realized that he was trying to tell me that he had now finished "Sometimes a Great Notion." Christ, I thought, there is no competing with this guy.

In 1962, he had published "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," a libertarian fable to suit the changing times. It had been a best-seller on publication, and has never been out of print. The book had also been adapted for a Broadway stage production starring Kirk Douglas, who then proposed to do it as a movie. Ken and Faye had gone to the opening night, in that era of formal first nights, with gowns and black tie. Now, a few months later, he had another thicket of epic novel clutched in his mitt, and for all I knew there'd be another one after that.

He really seemed capable of making anything happen. It was beyond writing- although, to me, writing was just about all there was. We sat and smoked and possibility came down on us.

Kesey was, more than anyone I knew, the grip of all that the sixties seemed to promise. Born in 1935 in a town called La Junta, Colorado, on the road west from the Dust Bowl, he had grown up in Oregon, where his father became a successful dairyman. At school, Kesey was a wrestling champion, and champion was still the word for him; it was impossible for his friends to imagine him losing, at wrestling or anything else. Leaving the dairy business to his brother Chuck, Kesey had become an academic champion as well, a Woodrow Wilson Fellow at Stanford.

Ken's endorsement, at the age of twenty-six, by Malcolm Cowley, who oversaw his publication at Viking Press, seemed to connect him to a line of "heavyweight" novelists, the hitters, as Norman Mailer put it, of long balls, the wearers of mantles that by then seemed ready to be passed along to the next heroic generation. If American literature ever had a favorite son, distilled from the native grain, it was Kesey. In a way, he personally embodied the winning side in every historical struggle that had served to create the colossus that was nineteen-sixties America; an Anglo-Saxon Protestant Western white male, an Olympic-calibre athlete with an advanced academic degree, he had inherited the progressive empowerment of centuries. There was not an effective migration or social improvement of which he was not, in some near or remote sense, the beneficiary. That he had been born to a family of sodbusters only served to complete the legend. It gave him the extra advantage of not being bound to privilege.

Some years before "Cuckoo's Nest," Ken had written an unpublished Nathanael West-like Hollywood story based on Kesey's unsuccessful attempt to break into the picture business as an actor. All his life, Ken had a certain fascination with Hollywood, as any American fabulist might. He saw it in semi-mythological terms- as almost an autonomous natural phenomenon rather than as a billion-dollar industry. (This touch of naive fascination embittered his later conflicts over the adaptation of his novels into films.) However, it was as a rising novelist and not as an actor or screenwriter that he faced the spring of 1964. There was no question of his limitless energy. But in the long run, some people thought, the practice of novel-writing would prove to be too sedentary an occupation for so quick an athlete- lonely, and incorporating long silent periods between strokes. Most writers who were not Hemingway spent more time staying awake in quiet rooms than shooting lions in Arusha.

Kesey was listening for some inner voice to tell him precisely what role history and fortune were offering him. Like his old teacher Wallace Stegner, like his friend Larry McMurtry, he had the Western artist's respect for legend. He felt his own power and he knew that others did, too. Certainly his work cast its spell. But, beyond the world of words, he possessed the thing itself, in its ancient mysterious sense. "His charisma was transactional," Vic Lovell, the psychologist to whom Kesey dedicated "Cuckoo's Nest," said to me when we spoke after Ken's death. He meant that Kesey's extraordinary energy did not exist in isolation- it acted on and changed those who experienced it. His ability to offer other people a variety of satisfactions ranging from fun to transcendence was not especially verbal, which is why it remained independent of Kesey's fiction, and it was ineffable, impossible to describe exactly or to encapsulate in a quotation. I imagine that Fitzgerald endowed Jay Gatsby with a similar charisma- enigmatic and elusive, exciting the dreams, envy, and frustration of those who were drawn to him. Charisma is a gift of the gods, the Greeks believed, but, like all divine gifts, it has its cost. (Kesey once composed an insightful bit of doggerel about his own promise to the seekers around him. "Of offering more than what I can deliver," it went, "I have a bad habit, it is true. But I have to offer more than I can deliver to be able to deliver what I do.")

Kesey felt that the world was his own creature and, at the same time- paradoxically, inevitably- that he was an outsider in it, in danger of being cheated out of his own achievement. His forebears had feared and hated the railroads and the Eastern banks. In their place, Kesey saw New York, the academic establishment, Hollywood. When he was growing up in Oregon, I imagine, all power must have seemed to come from somewhere else. Big paper companies and unions, the F.B.I. and the local sheriff's department- he distrusted them all.

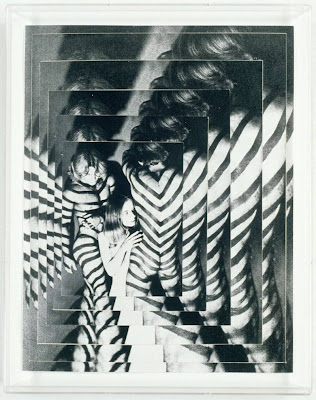

While in New York for the opening night of "Cuckoo's Nest," Kesey had caught a glimpse of the preparations for the 1964 World's Fair. It didn't take him long to dream up the idea of riding a bus to the fair, arriving sometime before the scheduled publication date for "Sometimes a Great Notion." Somehow, he and his friends the sports-car driver George Walker and the photographer Mike Hagen managed to buy a 1939 International Harvester school bus and refashion it into a kind of disarmed personnel carrier, with welded compartments inside and an observation platform that looked like a U-boat's conning tower on top. It was wired to play and record tapes, capable of belching forth a cacophony of psychic disconnects and registering the reactions at the same time. There were movie cameras everywhere. Everyone had a hand in the painting of the bus, principally the San Francisco artist Roy Sebern. A sign above the windshield, where the destination would normally be announced, proclaimed, "FURTHUR."

By then, there were a number of footloose wanderers loitering around Kesey's spread in La Honda, ready to ride as soon as the paint was dry- just waiting, really, for Kesey to tell them what to do next. It was said later that one was either on the bus or off the bus- no vain remark, mind you, but an insight of staggering profundity It meant, perhaps, that some who were physically on the bus were not actually on the bus in spirit. It meant that millions were off the bus, but the bus was coming for them. If you were willing to entertain Kerouac's notion that the blind jazz pianist George Shearing was God, that bus was coming for you.

I was going to New York, too- off the bus, though I expected to encounter it again. My wife, Janice, was attending City College, in Manhattan, and home was where she was. And I was at a strange point in my life. I had gone to the hospital for the treatment of what, in the days before CAT scans, was thought to be a brain tumor. The doctors, after shaving my head and pumping air into my cranium, playing my head like a calliope with their monstrous instruments, had decided that there was no tumor. Or, rather, there was a condition called pseudo-tumor, something that happens sometimes. I was conscious during the operation, on some kind of skull-deadener, so I remember snatches of medical conversation. "When you cut, cut away from the brain," one of the surgeons suggested. Another asked me if he could sing while he worked. Anyway, they sent me home alive and cured, and I was happy, albeit bald and with crashing headaches. I would forgo the bus trip.

California, the Menlo Park area around Stanford, was no longer home, but it had once been just short of paradise for me. In the cottages clustered among the live oaks, along the quiet streams that watered Herefords grazing on the yellow tule grass, the happiest time of my life had come and gone. Moving there from the wintry Lower East Side of New York, circa 1960, was like switching from black-and-white to color. One evening, Janice and I went to the Jazz Workshop, in San Francisco, to hear John Coltrane with some friends. We had boiled down peyote, poured the extract into pharmaceutical capsules, and ingested as much of the stuff as we could bear. I swallowed twelve. After sixty seconds of 'Trane, the percussion was undulating in great white waves of jagged frost, the serrated edges as symmetrical as if they had been drawn by an artist's hand. The brass erupted in bands of bright color, streaming out of the brazen instruments like a magicians silk. The entire Jazz Workshop was taken up by a wind from the edge of the earth. Synesthesia, I believe it's called, and I fled it. Janice and a friend of ours came after me. Outside was Chinatown. Its exotic effects were never as potent as they were for me that night.

Like everything that was essential to the sixties, the Kesey cross-country trip has been mythologized. If you can remember it, the old saw goes, you weren't there. But the ride in Ken's multicolored International Harvester school bus was a journey of such holiness that being there- mere vulgar location- was instantly beside the point. From the moment the first demented teenager waved a naked farewell as Neal Cassady threw the clutch, everything entered the numinous.

Who rode the bus, who rode it all the way to the World's Fair and all the way back, has become a matter of conjecture. The number has expanded like the opening-night audience for "Le Sacre du Printemps," a memorial multiplication in which a theatre seating eight hundred has come, over time, to accommodate several thousand eyewitnesses.

Who was actually on the bus? I, who waited, with the wine-stained manuscript of my first novel, for the rendezvous in New York, have a count. Tom Wolfe, who did not see the bus back then at all but is extremely accurate with facts, has a similar one. Cassady drove- the world's greatest driver, who could roll a joint while backing a 1937 Packard onto the lip of the Grand Canyon. Kesey went, of course. And Ken Babbs, fresh from Nam, full of radio nomenclature and with a command voice that put cops to flight. Jane Burton, a pregnant young philosophy professor who declined no challenges. Also George Walker; Sandy Lehmann-Haupt, whose electronic genius was responsible for the sound system. There was Mike Hagen, who shot most of the expedition's film footage. A former infantry officer, Ron Bevirt, whom everybody called Hassler, a clean-cut guy from Missouri, took photographs. There were two relatives of Kesey's- his brother Chuck and his cousin Dale- and Ken Babbs's brother John. Kesey's lawyer's brother-in-law Steve Lambrecht was along as well. And the beautiful Paula Sundsten.

To Ken, to America in 1964, World's Fairs were still a hot number. As for polychrome buses, one loses perspective; the Day-Glo vehicle full of hipsters is now such a spectral archetype of the American road. I'm not sure what it looked like then. With Cassady at the throttle, the bus perfected an uncanny reverse homage to "On the Road," traveling east over Eisenhower's interstates. Like "On the Road," the bus trip exalted velocity. Similarly, it scorned limits: this land was your land, this land was my land- the bus could turn up anywhere. It celebrated sunsets in four time zones, music on the tinny radio, tears in the rain. If the roadside grub was not as tasty as it had been in Kerouac's day, at least the highway grades were better.

Ken had had an instinctive distaste for the metropolis and its pretensions. He was not the only out-of-town writer who thought it a shame that so many publishers were based in New York, and he looked forward to a time when the book business would regionally diversify, supposedly bringing our literature closer to its roots in American soil. But the raising of a World's Fair in the seething city was to Kesey both a breath of assurance and a challenge. Fairs and carnivals, exhibitional wonders of all sorts, were his very meat. He wondered whether the big town would trip over its own grandiose chic when faced with such a homespun concept. Millions were supposed to be coming, a horde of visitors foreign and domestic, all expecting the moon.

The bus set off sometime in June. Nineteen-sixty-four was an election year. To baffle the rubes along their route, Kesey and Cassady had painted a motto over the psychedelia on the side of the bus - "A Vote for Barry Is a Vote for Fun"- hoping to pass for psychotic Republicans hyping Goldwater. The country cops of the highways and byways, however, took them for gypsies and waved them through one town after another. Presumably, the vaguely troubled America that was subjected to this drive-by repressed its passing image as meaningless, a hallucination. Sometime around then, someone offered a lame joke in the tradition of Major Hoople, something about "merry pranksters." (Major Hoople- a droll comic-strip character at the time, the idler husband of a boarding-house proprietress- was one of Cassady's patron gods.) The witless remark was carried too far, along with everything else, and for forty years thereafter people checked for the clownish fringe at our cuffs or imagined us with red rubber noses.

Eventually, the bus pulled up in front of the apartment building on West Ninety-seventh Street, in New York, where Janice and I were living with our two children. Our apartment was notorious among our friends for its ugliness and brick-wall views. Suddenly, the place was tilled with people painted all colors. The bus waited outside, unguarded, broadcasting Ray Charles, attracting hostile attention with its demented Goldwater slogan. We and the kids took our places on top of the bus, ducking trees on our way through Central Park Downtown; a well-fed button man came out of Vincent's clam bar to study the bus and the tootling oddballs on its roof. He paused thoughtfully for a moment and finally said, "Get offa there!" That seemed to be the general sentiment. Other citizens offered the finger and limp-wristed "Heil Hitler"s. Later, the gang drove the bus to 125th Street. The street was going to burn in a few weeks, and, but for the mercy of time, some pranksters would have burned with it.

There was the after-bus party, where Kerouac, out of rage at our health and youth and mindlessness- but mainly out of jealousy at Kesey for hijacking his beloved sidekick, Cassady- despised us, and wouldn't speak to Cassady, who, with the trip behind him, looked about seventy years old. A man attended who claimed to be Terry Southern but wasn't. I asked Kerouac for a cigarette and was refused. If I hadn't seen him around in the past I would have thought that this Kerouac was an impostor, too- I couldn't believe how miserable he was, how much he hated all the people who were in awe of him. You should buy your own smokes, said drunk, angry Kerouac. He was still dramatically handsome then; the next time I saw him he would be a red-faced baby, sick and swollen. He was a published, admired writer, I thought. How could he be so unhappy? But we, the people he called "surfers," were happy. We left the party and drove to a bacchanal and snooze in Millbrook, New York, where death and transfiguration had replaced tournament polo as a ride on the edge.

The bus riders visited the fair in a spirit of decent out-of-town respect for the power and glory of plutocracy They filmed everything in sight and recorded everything in earshot. Like most young Americans in 1964, they were committed to the idea of a World's Fair as groovy, which in retrospect can only be called sweet. Sweet but just the least bit defiant. Also not a little ripped, since driver and passengers had consumed mind-altering drugs in a quantity and variety unrivalled until the prison pharmacy at the New Mexico state penitentiary fell to rioting cons.

And, of course, the fair was a mistake for everyone. Now we know that World's Fairs are always bad news. In 1939, the staff of a few national pavilions in New York had nothing to tell the world except that their countries no longer existed. The hardware of national gewgaws and exhibits went as scrap metal to the war effort. In 1964, the fair produced nothing but sinister urban legends in unsettling numbers, grisly stories of abduction, murder, and coverups. Children were said to have disappeared. Body parts were allegedly concealed in the sleek aluminum spheres and silos. It was the hottest summer in many years. Some of the passengers were so long at the fair that they went home without their souls. Jane, the philosophy professor, insists to this day that she made it to the fair only because she had lost her purse on the first day of the trip. Back in California, she became a mother and went to law school. Kesey and Cassady went home, too. Fame awaited them, along with the same fascinated loathing that Kerouac and Ginsberg had endured. We couldn't imagine it at the time, but we were on the losing side of the culture war.

It was a war that got meaner as the world got smaller. Ginsberg and Kerouac, in the fifties, had been set upon by illiterate feature writers concocting insulting lies about their personal hygiene and reporting the clever wisecracks that famous people were supposed to have delivered at their expense. Now the drug thing was being used to make the wrongos feel the fire. At the end of the fifties, Cassady, who was not exactly the Napoleon of crime, had done two years in San Quentin for supposedly selling a few joints. Sometime after Kesey's return to California, in 1965, his house in La Honda was raided during a party. The native country he had just visited in such state was biting back. Ken and some friends were charged with possession of narcotics. Then, on a San Francisco rooftop one foggy night, while watching the Alcatraz searchlight probe the bay's radius, he was arrested again on the same charge. At this, he and his friends composed a giggly, overwrought suicide note addressed to the ocean. ("0 Ocean," it began, grimly omitting the "h" to indicate high seriousness and despair.) Fleeing south, Kesey made it to the same area in Mexico where Ram Dass and other prototypical acid cranks had conducted their early séances.

In New York, I got a telegram that declared "Everything Is Beginning Again," an Edenic prospect I had no power to resist. I had finally finished my novel, but it would not be published for months, and I was at the time employed by what our lawyers called "a weekly tabloid with a heavy emphasis on sex." I had not published anything much beyond "SKYDIVER DEVOURED BY STARVING BIRDS" and "WEDDING NIGHT TRICK BREAKS BRIDE'S BACK"- fables of misadventure and desperate desire for the distraction of the supermarket browser. Nevertheless, I was the only person Esquire could find who knew where Kesey was. By then, his work and his drug-laced adventures in a transforming San Francisco were well known. Esquire paid my way south.

It was the autumn of 1966, and Ken, Faye, their children, and some of their friends were staying near Manzanillo. In 1966, the Pacific Coast between Zihuatanejo and Puerto Vallarta did not look the way it looks today. The road ran for many miles along the foot of the Sierra Madre, bordering an enormous jungle crowned by the Colima volcano itself. The peak thrust its fires nearly four thousand metres into the clouds. At the edge of the mountains, the black-and-white sand beach was so empty that you could walk for hours without passing a town, or even the simplest dwelling. The waves were deafening, patrolled by laughing gulls and pelicans.

Today, Manzanillo is Mexico's biggest Pacific port and the center of an upscale tourist area. In those days, it seemed like the edge of the world, poor and beautiful beyond belief. One of the hotels in town advertised its elevator on a sandwich board outside. Manzanillo's commanding establishment was a naval base that supported a couple of gunboats.

The Keseys' home was a few miles beyond the bay in a complex of three concrete buildings with crumbling roofs, partly enclosed by a broken concrete wall. We called one of the buildings Casa Purina. Despite its chaste evocations, the name derived from the place's having once housed some operation of the Purina company, worldwide producers of animal feed and aids to husbandry. In the sheltered rooms, we stashed our gear and slung our hammocks. We occupied our time seeking oracular guidance in the I Ching and pursuing now vanished folk arts, like cleaning the seeds from our marijuana. (Older heads will remember how the seeds were removed from bud clusters by shaking them loose onto the inverted top of a shoebox. Since the introduction of seedless dope, this homely craft has gone the way of great-grandma's butter churn.)

Our landlord was a Chinese-Mexican grocer, who referred to us as existencialistas, which we thought was a good one. He provided electricity, which enabled us to take warm showers and listen to Wolfman Jack and the Texaco opera broadcasts on Saturday. No trace remained, fortunately, of whatever the Purina people had been up to between those whitewashed walls.

We were an unstable gathering, difficult to define. The California drug police, whatever they were called at that time, professed to believe that we were a gang of narcotics smugglers and criminals, our headquarters hard to locate, perhaps protected by the local crime lords. In fact, we were a cross between a Stanford fraternity party and an underfunded libertine writers' conference.

We had no nearby neighbors except the grocery store, and most people along the coast hardly knew we were there, at first. The Casa was far from town, and there was little traffic along the intermittently paved highway that wound over the Sierra toward Guadalajara. It consisted mainly of the local buses, whose passengers might spot our laundry hanging in the salt breeze or glimpse our puppy pack of golden-haired kiddies racing over black sand toward the breakers. Several times a day, the gleaming first-class coaches of the Flecha Amarilla company would hurtle past, a streak of bright silver and gold, all curves and tinted glass. With their crushed Air Corps caps and stylish sunglasses, the Flecha Amarilla drivers were gods, eyeball to eyeball with fate. Everything and everyone along the modest road gave way to them.

In appreciation of the spectacle they offered, these buses sometimes drew a salute from Cassady. He would stand on a ruined wall and present arms to the bus with a hammer, which for some reason he carried everywhere in a leather holster on his hip. How the middle-class Mexican coach passengers reacted to the random instant of Neal against the landscape I can only imagine. Sometimes he brought his parrot, Rubiaco, in its cage, holding it up so that Rubiaco and the Flecha Amarilla passengers could inspect each other, as though he were offering the parrot for sale. Cassady in Manzanillo was extending his career as a character in other people's work- Kerouac had used him, as would Kesey, Tom Wolfe, and I. The persistent calling forth and reinventing of his existence was an exhausting process even for such an extraordinary mortal as Neal. Maybe it has earned him the immortality he yearned for. It certainly seems to have shortened his life.

People who live in the tropics sometimes claim to have seen a gorgeous green flash spreading out from the horizon just after sunset on certain clear evenings. Maybe they have. Not me. What I will never forget is the greening of the day at first light on the shores north of Manzanillo Bay. I imagine that color so vividly that I know, by ontology, that I must have seen it. In the moments after dawn, before the sun had reached the peaks of the Sierra, the slopes and valleys of the rain forest would explode in green light, erupting inside a silence that seemed barely to contain it. When the sun's rays spilled over the ridge, they discovered dozens of silvery waterspouts and dissolved them into smoky rainbows. Then the silence would give way and the jungle noises rose to blue Heaven. Those mornings, day after day, made nonsense of the examined life, but they made everyone smile. All of us, stoned or otherwise, caught in the vortex of dawn, would freeze in our tracks and stand to, squinting in the pain of the light, sweating, grinning. We called that light Prime Green; it was primal, primary, primo.

The high-intensity presence of Mexico was inescapable. Even in the barrancas of the wilderness, you felt the country's immanence. Poverty, formality, fatalism, and violence seemed to charge even uninhabited landscapes. I was young enough to rejoice in this. On certain mornings, when the tide was low and the wind came from the necessary quarter, you could stand on the beach and hear the bugle call from the naval base in the city. Although it had a brief section that suggested Tchaikovsky's "Capriccio Italien," the notes of the Mexican call to colors were pure heartbreak. They always suggested to me the triumphalism of the vanquished, the heroic, engaged in disastrous sacrifice. Those were the notes that had called thousands of lancers against the handful of Texans at the Alamo, that had called wave after wave of Juarez's soldiers against the few dozen Foreign Legionnaires at Camerone. Had the same strains echoed off the rock of Chapultepec when the young cadets wrapped themselves in the flag and leaped from the Halls of Montezuma to defy the Marines?

Does any other army figure so large in the romantic institutional memories of its enemies? All those peasant soldiers, underequipped in everything but the courage for Pyrrhic victories and gorgeous suicidal gestures. Naifs led by Quixotes against grim nameless professionals with nothing to lose, loyal to their masters' greed.

So our exile provided more than a hugely spectacular scenic backdrop. The human setting, never altogether out of view, was ongoing conflict. Quite selfishly, we loved the color of history there, the high drama-man at his fiercest. We imagined it all flat out, as presented by Rivera, Orozco, and the rest, the dark and light, La Adelita, El Grito, Malinche. Hard-riding rebeldes, leering calaveras, honor, betrayal, the songs of revolution. We had ourselves an opera. Or, as someone remarked, a Marvel comic. All this naturally gave our own lives a quality of fatefulness and melodrama. We were fugitives, after all- at least, Kesey was.

0ne thing we failed to grasp in 1966 was that Mexico was a nation at a turning point. Time and geography had caused it to require many things of the United States, but a band of pot-smoking, impoverished existencialistas who danced naked on the beach and frightened away the respectable tourists was simply not one of them. Gradually, as our presence made itself manifest, it drew crowds of the curious. Young people, especially, were fascinated by the anarchy, by the lights and the music. The local authorities became watchful. At that time, marijuana was disapproved of in Mexico, associated with a low element locally and with the kind of unnecessary gringos who lived on mangoes and whose antics encrimsoned the jowls of free-spending trophy fishermen from Orange County. From the start, I think, the authorities in the state of Colima understood that there was more hemp than Heidegger at the root of our cerebration, and that many of us had trouble distinguishing Being from Nothingness by three in the afternoon. At the same time, a sort of fix was in: Ken was paying mordida through his lawyers, enough to deter initiatives on the part of law enforcement.

We were bearing witness, unwittingly, to a worldwide development that had begun in the United States. The original laws forbidding classified substances had been conceived in the language of therapy, emphasizing the discouragement of such addictive nostrums as "temperance cola" and cocaine tonics. From the fright tabloid to the police blotter the matter went, providing the founding documents of a police underworld, featuring informers, jail time, and the third degree. The resulting damage to American and foreign jurisprudence, the outlaw fortunes made, the destroyed children, and the gangsterism are all well known. What had been a way for Indian workmen to reinforce the pulque they drank and sweated out by sundown, a disagreeable practice of the hoi polloi, became, once it was established as a police matter, Chicago-style prohibition on a global scale. Nothing on earth was more serious than people getting loaded, America was told. Nothing, travelers found, so preoccupied stone-faced cops from Mauretania to Luzon as the possibility of a joint in a sock, hash in a compact.

In Mexico, we failed to interpret the developments on the drug front to such a degree that when a plainclothes Mexican policeman- Agent No. 1, as he described himself- appeared to make awkward probing conversation with us in the local cantina we were more amused by his stereotypical overbearing manner than alarmed. We should have seen the deadly future he represented.

Some twenty years earlier, Cassady had brought Kerouac down to Mexico and revealed it to him as the happy end of the rainbow. In "On the Road," Kerouac records the dreamy observations of Cassady's character, Dean Moriarty, as he provides his companero- Jack in the role of Sal Paradise- with lyrical insights into a Land That Care Forgot, Mexico as a garden without so much as the shadow of a snake. "Oh this is too great to be true," Dean exults, from the moment their jalopy clears Nuevo Laredo. "Damn" and "What kicks!" and "Oh, what a land!" Like his model, he goes on at length:

Sal, I am digging the interiors of these homes as we pass them- these gone doorways and you look inside and see beds of straw and little brown kids sleeping and stirring to wake, their thoughts congealing from the empty mind of sleep, their selves rising and the mothers cooking up breakfast in iron pots, and dig them shutters they have for windows and the old men, the old men are so cool and grand and not bothered by anything. There's no suspicion here, nothing like that. Everybody's cool, everybody looks at you with such straight brown eyes and they don't say anything, just look. and in that look all of the human qualities are soft and subdued and still there.

In 1957, I had sat in the radio shack of the U.S.S. Arneb, a young sailor with my earphones tuned to Johnson and Winding, reading all this in the copy of "On the Road" that my mother had sent me. If it seems strange that my copy of this hipster testament came from my mother, it would have seemed far more improbable- at least, to me- that I would one day be sharing the mercies of Mexico with some of the characters from the book. Nor would I have believed that anyone, anywhere, ever, talked like Dean Moriarty. I was twice wrong, and, as they say, be careful what you wish for.

As we sat in the cantina, watching Agent No. 1 grow more drunk and less convivial with every round, I began to see that Dean Moriarty and his author had been mistaken in some respects. In the bent brown eyes of the agent, I beheld grave suspicion, and my own thoughts began to congeal around the prospect of waking up to breakfast in a Mexican jail.

There are working-class taverns in Mexico (and some pretty fancy ones, too) where the drinking atmosphere seems to change over the course of a few hours in a manner that is somewhat the reverse of similar establishments in other countries. For example, a customer might arrive in the early evening to find the place loud with laughter and conversations about baseball or local politics and gossip, the jukebox blaring, the bartender all smiles. Then, as time progressed and the patrons advanced more deeply into their liquor, things would seem to quiet down. By a late hour, the joint, just as crowded, would grow so subdued that the rattle of a coin on the wooden bar might attract the attention of the whole room. Men who had been exchanging jokes a short time before would stand unsteadily and look around with an unfocussed caution, as though reassessing the place and their drinking buddies. These reassessments sometimes seemed unfavorable, at which point it was time to leave.

Thus it went with Agent No. 1. He showed us his badge and indeed it was embossed with the number 1 and he assured us that, as cops went, he was numero uno as well. He told stories about Elizabeth Taylor in Puerto Vallarta - how her stolen jewelry was returned at the very whisper of his name in the criminal hangouts of P.V. His mood kept deteriorating. He got drunker and would not go away. He told us that Mexico's attitude toward marijuana was very liberal. His private attitude was, too, though he never used drugs himself, no, no, no. Did we know that we were entitled to keep some marijuana for our own personal use? Quite a generous amount. I have come to recognize the phrase "your own personal use" employed in a tone of good-natured tolerance as a standard police trap around the world; whatever you admit to possessing is likely to get you put away.

While I let the federale buy me drinks, my two companions teased him as though we were all players in "A Touch of Evil." Ken Babbs's Vietnam post-traumatic stress took the form of a dreadful fearlessness, which, though terrifying to timid adventurers like myself, would come in handy more than once. George Walker had a similar spirit. For my part, I went for the persona of one polite but dumb, an attitude that annoyed the agent even more than Babbs's and Walker's transparent mockery. For some inexplicable reason, I thought I could mollify him by talking politics. The agent was an anti-Communist and excitable on the topic. I have come to realize that in the context of Mexico in 1966 this portended no good. Eventually, having bought every round and rather fumbled his exploratory probe, Agent No. 1 climbed into his Buick and drove off toward Guadalajara. His hateful parting glance told us that this was hasta luego, not adios.

We reported out encounter to Kesey, who was philosophical; he had been brooding, wandering the beach at night. In the morning, he would come back to sleep, exhausted, looking for Faye to lead him to cool and darkness, shelter from the green blaze and the reenactment of creation that could explode at any moment. What was happening to Kesey? He didn't seem to be writing much. It was impossible to tell if we were witnessing a stage of literary development, a personal Gethsemane, or an apotheosis. Some fundamental change seemed to be taking place in the world, and as he smoked the good local herb on the slope of the Sierra and watched the lightning flashes and the fires of the volcano he pondered what his role in it might be. Before his flight to Mexico, he had attended a Unitarian conference at Asilomar, on the California coast, during the course of which a number of people had come to believe that he was God. He had spun their minds with unanswerable gnomic challenges and imaginary paradoxes. Still, it was an especially heady compliment, coming from the Unitarians. Kesey referred to the Unitarian elders, patrician world citizens in sailor caps and fishermen's sweaters, as "the pipes," because they took their tobacco in hawthorn- and maple-scented meerschaums and used the instruments to punctuate their thoughtful, humane fireside remarks. "If you've got it all together," Kesey asked one confounded elder, "what's that all around it?"

Local adolescents took to hanging out at the Casa. Some of them were musicians. On the anniversary of Mexican independence, we decided to hold what someone called an acid test. People appeared on the beach with rum and firecrackers. We put tricolor Mexican bunting up. By this point, Cassady had found it liberating to restrict his diet to methamphetamine. He went everywhere with Rubiaco, the parrot. So constant was their companionship, so exact was Rubiaco's rendering of Cassady's speech, that without looking it was impossible to tell which of them had come into a room. As for Cassady on amphetamine- he never ate, never slept, and never shut up. He also thought it a merry prank to slip several hundred micrograms of LSD into anything anyone happened to be ingesting. No one dared eat or drink without secure refuge from Neal. To cap off our Independence Day celebration, a number of us went into the village market and bought a suckling pig for roasting. Nothing roasted ever smelled lovelier to me than that substance-free pig as we settled under the palms with our paper plates and bottles of Pacifico. We were, unfortunately, deceived. Cassady had shot the creature in vivo with a hypo full of LSD, topped off with his choicest methedrine. After two forkfuls of lechón, we were bug-eyed, watching the Dance of the Diablitos, every one of us deep in delusion.

How the parrot survived its friendship with Cassady is beyond me; as far as I remember, neither he nor anyone else ever fed the bird. Twenty-five years later, on Kesey's farm, Janice and I woke to Neal's voice from the beyond. (The man himself had died by the railroad tracks outside San Miguel de Allende in 1968.) "Fuckin' Denver cops," he muttered bitterly. "They got a grand theft auto. I tell them that ain't my beef?" We rose bolt upright and found ourselves staring into Rubiaco's unkindly green eye. If, as some say, parrots live preternaturally long lives, it must be time for some literary zoologist to cop that bid for the University of Texas Library Zoo.

The expatriation had to come to an end, Kesey would have to go back and answer to the State of California. In fact, his spell on the lam had been excellently timed. In 1966, the world, and especially California, was changing fast. The change was actually visible on the streets of San Francisco, at places like the Fillmore and the Avalon Ballroom. Political and social institutions were so lacking in humor and self-confidence that they crumbled at a wisecrack. The Esquire consciousness, however, held firm- they declined my copy. "For Christ's sake," an editor kept telling me, "tell it to a neutral reader." They thought I had gone native on the story, and of course I had been pretty native to begin with.

A few months later, Kesey crossed the border and went home. He was able to make a deal for six months at the San Mateo County sheriff's honor farm. No man can call another's prison time easy, but Kesey's was less bitter medicine than Cassady's two years at San Quentin. It was also an improvement on five years to life, a standard sentence on the books for a high-profile defendant at the time of Kesey's arrest.

Over the years, my friend Ken became a libertarian shaman. Above all, he loved performing; he loved preaching and teaching. He was a wonderful father, a fearless and generous friend, who always took back far less than he gave. All his life, he was searching for the philosopher's stone that could return the world to the pure story from which it was made, bypassing syntax and those damn New York publishers. He kept trying to find the message beyond the words, to see the words that God had written in fire. He traveled around sometimes, in successors to the old bus, telling stories and putting on improvised shows for crowds of children and adults. If he had chosen to work through his progressively revealed mythology in novels, rather than trying to live it out all at once, he might have become a writer for the age.

Life had given Americans so much by the mid-sixties that we were all a little drunk on possibility. Things were speeding out of control before we could define them. Those who cared most deeply about the changes, those who gave their lives to them, were, I think, the most deceived. While we were playing shadow tag in the San Francisco suburbs, other revolutions were counting their chips. Curved, finned, corporate Tomorrowland, as presented at the 1964 World's Fair, was over before it began, and we were borne along with it into a future that no one would have recognized, a world that no one could have wanted. Sex, drugs, and death were demystified. The LSD we took as a tonic of psychic liberation turned out to have been developed by C.I.A. researchers as a weapon of the Cold War. We had gone to a party in La Honda in 1963 that followed us out the door and into the street and filled the world with funny colors. But the prank was on us.

*06/14/2004 The New Yorker.

**Robert Stone