Peter Thiel on The Future of Legal Technology - Notes Essayblakemasters.tumblr.comHere is an essay version of my notes from Peter Thiel’s recent guest lecture in Stanford Law’s Legal Technology course. As usual, this is not a verbatim transcript. Errors and omissions are my own. Credit for good stuff is Peter’s.

When thinking about the future of the computer age, we can think of many distant futures where computers do vastly more than humans can do. Whether there will eventually be some sort of superhuman-capable AI remains an open question. Generally speaking, people are probably too skeptical about advances in this area. There’s probably much more potential here than people assume.

It’s worth distinguishing thinking about the distant future—that is, what could happen in, say, 1,000 years—from thinking about the near future of the next 20 to 50 years. When talking about legal technology, it may be useful to talk first about the distant future, and then rewind to evaluate how our legal system is working and whether there are any changes on the horizon.

I. The Distant Future

The one thing that seems safe to say about the very distant future is that people are pretty limited in their thinking about it. There are all sorts of literary references, of course, ranging from 2001: A Space Odyssey to Futurama. But in truth, all the familiar sci-fi probably has much too narrow an intuition about what advanced AI would actually look like.

This follows directly from how we think about computers and people. We tend to think of all computers as more or less identical. Maybe some features are different, but the systems are mostly homogeneous. People, by contrast, are very different from one another. We look at the wide range of human characteristics—from empathy to cruelty, kindness to sociopathy—and perceive people to be quite diverse. Since people run our legal system, this heterogeneity translates into a wide range of outcomes in disputes. After all, if people are all different, it may matter a great deal who is the judge, jury, or prosecutor in your case. The converse of this super naive intuition is that, since all computers are the same, an automized legal system would be one in which you get the same answer in all sorts of different contexts.

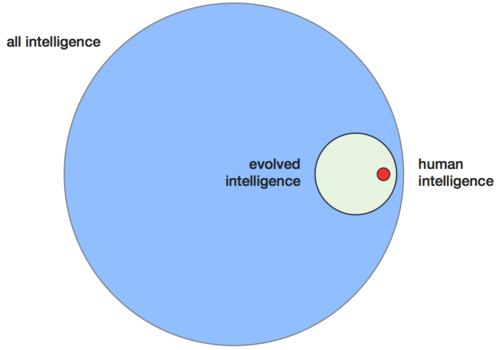

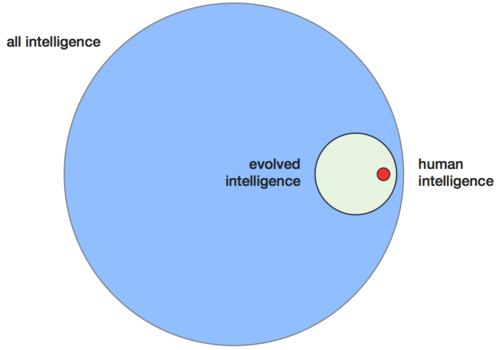

This is probably backwards. Suppose you draw 3 concentric circles on a whiteboard: one dot, a ring around that dot, and a larger circle around that ring. The range of all possible humans best corresponds with the dot. The ring around the dot corresponds to all intelligent life forms; it’s a bigger range comprised of the superset of all humans, plus Martians, Alpha Centaurians, Andromedans, and so on. But the diversity of intelligent life is still constrained by evolution, chemistry, and biology. Computers aren’t. So the set of all intelligent machines would be the superset of all aliens. The range and diversity of possible computers is actually much bigger than the range of possible life forms under known rules.

What Hal will be like is thus a much harder question than knowing what would happen if Martians took control of the legal system.

The point is simply this: we have all sorts of these intuitions about computers and the future, and they are very incomplete at best. Implementation of all these diverse machines and AIs might produce better, worse, or totally incomprehensible systems. Certainly we hope for the former as we work toward building this technology. But the tremendous range these systems could occupy is always worth underscoring.

II. The Near Future

Let’s telescope this back to the narrower question of the near future. Forget about 1,000 years from now. Think instead what the world will look like 20 to 50 years from now. It’s conceivable, if not probable, that large parts of the legal system will be automated. Today we have automatic cameras that give speeding tickets if you drive too fast. Maybe in 20 years there will be a similarly automated determination of whether you’re paying your taxes or not. There are many interesting, unanswered questions about what these systems would be like. But our standard intuition is that it’s all pretty scary.

This bias is worth thinking really hard about. Why do we think that a more automated legal future is scary? Of course there may be problems with it. Those merit discussion. But the baseline fear of computers in the near term may actually tells us quite a bit about our current system.

A. Status Quo Bias

Let’s look at our current legal system de novo. Arguably, it’s actually quite scary itself. There are lots of crimes and laws on the books—so many, in fact, that it’s pretty obvious that the system simply wouldn’t work if everybody were actually held accountable for every technical violation. You can guess the thesis of Silverglate’s book Three Felonies A Day. Is that exaggerated? Maybe. But one suspects there’s a lot to it.

The drive for regulation and enforcement by inspection isn’t new or unique to America, of course. In 1945, the English playwright J.B. Priestley wrote a play called An Inspector Calls. The plot involves the mysterious death of a nanny who was working for an upper middle class family. The family insists it was just suicide, but an inspector investigates and finds that the family actually did all these bad things to drive the girl to suicide. The subtext is all of society is like this. The play opened in 1945 at the Bolshevik Theatre in Stalinist Russia. The last line was: “We must have more inspectors!” And the curtains closed to thunderous applause.

B. Fear of the Unknown

Despite firsthand knowledge of what bureaucracy can do, we tend to think that it is a computerized legal system that would be incredibly draconian and totalitarian. For some reason, there is a big fear of automatic implementation and it gets amplified as people extrapolate into the future.

The main pushback to this view is that it ignores the fact that the status quo is actually quite bad. Very often, justice isn’t done. Too often, things are largely arbitrary. Incredibly random events shape legal outcomes. Do people get caught? Given wide discretion, what do prosecutors decide to do? What goes on during jury selection? It seems inarguable that, to a large extent, random and uncertain processes determine guilt or liability. This version isn’t totalitarian, but it’s arbitrary all the same. We just tend not to notice because most of the time we get off the hook for stuff we do. So it sort of works.

C. Deviation from Certainty

But what is the nature of the randomness? That our legal system deviates from algorithmic determinism isn’t necessarily bad. The question is whether the deviation is subrational or superrational. Subrational deviation involves things that don’t make sense, but rather just happen for no reason at all. Maybe a cop is upset about something from earlier in the day and he takes it out on you. Or maybe the people on the jury don’t like how you look. People don’t like to focus on these subrational elements. Instead they prefer to talk as if all deviation were superrational: what’s arbitrary is not in fact arbitrary, but rather is perfect justice. Things are infinitely complex and nuanced. And our current system—but not predictable computers—appropriately factors all that in.

That narrative sounds good, but it probably isn’t true. Most deviation from predictability in our legal system is probably subrational deviation. In many contexts, this doesn’t matter all that much. Take speeding tickets, for example. Everyone gets caught occasionally, with roughly the same frequency. Maybe a system with better enforcement and lesser penalties would be slightly better, but one gets the sense that this isn’t such a big deal.

But there are more serious cases where the sub- vs. superrational nature of the deviation matters more. Drug laws are one example. This past election, Colorado voters just voted to legalize marijuana there. California has done something functionally similar by declaring that simple possession is not an enforcement priority. But that’s only at the state level; possession remains illegal and enforced under federal law. Violation of the federal statute can and does mean big jail time for people who get caught. But the flipside is that there aren’t many federal enforcers, and these states aren’t inclined to enforce the federal law themselves. So people wind up having to do a bunch of probabilistic math. Maybe a regime in which you have a 1 in 1,000 chance of going to jail for a term of 1,000 days works reasonably well. But arguably it’s quite arbitrary; getting caught can feel like getting hit with a lightening bolt. Much better would be to have 1,000 offenders each go to jail for a day.

III. A (More) Transparent Future

It may be that the usual intuition is precisely backwards. Computerizing the legal system could make it much less arbitrary while still avoiding totalitarianism. There is no reason to think that automization is inherently draconian.

Of course, automating systems has consequences. Perhaps the biggest impact that computer tech and the information revolution have had over last few decades has been increased transparency. More things today are brought to the surface than ever before in history. A fully transparent world is one where everyone gets arrested for the same crimes. As a purely descriptive matter, our trajectory certainly points in that direction. Normatively, there’s always the question of whether this trajectory is good or bad.

It’s hard to get a handle on the normative aspect. What does it mean to say that “transparency is good”? One might say that transparency is good because its opposite is criminality, which we know is bad. If people are illegally hiding money in Swiss bank accounts, maybe we should make all that transparent. But it’s just as easy to claim that opposite transparency is privacy, which we also tend to believe is good. Few would argue that the right to privacy is the same thing as the right to commit crimes in total secrecy.

One way to these questions is to first distinguish the descriptive and the normative and then hedge. Yes, the shift toward transparency has its problems. But it’s probably not reversible. Given that it’s happening, and given that it can be good or bad depending on how we adjust, we should probably focus on adjusting well. We’ll have to rethink these systems.

A. Transparency and Procedure

In some sense, Computers are inherently transparent. Almost invariably, codifying and automating things makes them more transparent. From the computer revolution perspective, transparency involves more than simply making people aware of more information. Things become more transparent in a deeper, structural sense if and when code determines how they must happen.

One considerable benefit of this kind of transparency is that it can bring to light the injustices of existing legal or quasi-legal systems. Consider the torture scandals of the last decade. This got a lot of attention when information about what kinds of abuse were going on was published. This, in turn, led to a lot of changes in process, with the end result being a rather creepy formalization under which you can sort of dunk prisoners in water… but don’t you dare shock them.

Why the drive toward transparency? One theory is that lower level people were getting pretty nervous. They understandably wanted the protection of clear guidelines to follow. They didn’t have those guidelines because the higher ups in the Bush administration didn’t really understand how the world was changing around them. So it all came to a head. In an increasingly transparent world, torture gets bureaucratized. And once you formalize and codify something, you can bring it to the surface and have a discussion about whatever injustice you may see.

If you’re skeptical, ask yourself which is safer: being a prisoner at Guantanamo or being a suspected cop killer in New York City. Authorities in the latter case are pretty careful not to formalize rules of procedure. It seems reasonable to assume that’s intentional.

B. Would Transparency Break The Law?

The overarching, more philosophical question is how well a more transparent legal system would work. Transparency makes some systems work better, but it can also make some systems worse.

So which kind of system is the legal system? Maybe it’s like the stock market, which automation generally makes more efficient. Instead of only being able to trade to an eighth of a share, you can now trade to the penny. Traders now have access to all sorts of metrics like bidder volume. Things have become less arbitrary, more precise, and more efficient. If the law is mostly rational, and just slightly off, it may be the case that you can tweak things and make it right with a little automation.

Other systems aren’t like this at all. Many things only work when they are done in the dark, when no one knows exactly what’s going on. The phenomenon of scapegoating is a good example. It only works when people aren’t aware of it. If you were to say “We have a serious problem in the community. No one is happy. We need psychosocial process whereby we can designate someone as a witch and then burn them in order to resolve all this tension,” the idea would be ruined. The whole thing only works if people remain ignorant about it.

The question can thus be reduced to this: is the legal system pretty just already, and perfectible like a market? Or is it more arbitrary and unjust, like a psychosocial phenomenon that breaks down when illuminated?

The standard view is the former, but the better view is the latter. Our legal system is probably more parts crazed psychosocial phenomenon. The naïve rationalistic view of transparency is the market view; small changes move things toward perfectibility. But transparency can be stronger and more destructive than that. Consider the tendency to want to become vegan if you watch a bunch of foie gras videos on YouTube. Afterwards, you’re not terribly concerned about small differences in production techniques or the particulars of the sourcing of the geese. Rather, you have seen the light, and have a big shift in perspective. Truly understanding our legal system probably has this same effect; once you throw more light on it, you’re able to fully appreciate just how bad things are underneath the surface.

C. Law and Order

Once you start to suspect that the status quo is quite bad, you can ask all sorts of interesting questions. Are judges and juries rational deliberating bodies? Are they weighing things in a careful, nuanced way? Or are they behaving irrationally, issuing judgments and verdicts that are more or less random? Are judges supernaturally smart people? The voice of the people? The voice of God? Exemplars of perfect justice? Or is the legal system really just a set of crazy processes?

A good rule of thumb in business is to never get entangled in the legal system in any way whatsoever. Invariably it’s an arbitrary and expensive distraction from what you’re actually trying to do. People underestimate the costs of engaging with plaintiff’s lawyers. It’s very easy to think: “Well, they’re just bringing a case. It will cost a little bit, but ultimately we will figure out the truth.” But that’s pretty idealized. If you’re dealing with a crazy arbitrary system and you never actually know what could happen to you, you end up negotiating with plaintiff’s lawyers just like the government negotiates with terrorists: not at all, except in every specific instance. When the machinery is too many parts random and insane, you always find a way to pay people off.

Looking forward, we can speculate about how things will turn out. The trend is toward automization, and things will probably look very different 20, 50, and 1000 years from now. We could end up with a much better or much worse system. But realizing that our baseline may not be as good as we tend to assume it is opens up new avenues for progress. For example, if uniformly enforcing current laws would land everyone in jail, and transparency is only increasing, we’ll pretty much have to become a more tolerant society. By placing the status quo in proper context, we will get better at adjusting to a changing world.

Questions from the Audience:

Question from the audience: Judge Posner recently opined in a blog post that humans don’t have free will. He argued that it is not objectionable to heavily tax wealthy people because, things being thoroughly deterministic, they made their fortunes through random chance and luck. If the free will point is true, there are also implications for criminal law, since there’s no point punishing people who are not morally culpable. How do you see technological advance interacting with the questions of free will, determinism, and predicting people’s behavior?

Peter Thiel: There are many different takes on this. For starters, it’s worth noting that any one big movement on this question might not shake things up too much. Maybe you don’t aim for retribution on people who aren’t morally culpable. But there are other arguments for jail even if you don’t believe in free will. Since there are several competing rationales for the criminal justice system, practically speaking it may not matter.

More abstractly, it seems clear that we are headed towards a more transparent system. But there are layers and layers of nuance on what that means and how that happens. There is no one day where some switch will be flipped and everything is illuminated. Theoretically, if you could flip that switch and determine all the precise causal connections between things, you would know how everything worked and could create that perfectly just system. But philosophically and neurobiologically, that is probably very far away. Much more likely is a rolling wave of transparency. More things are transparent today than in the past. But there’s a lot that is still hidden.

The order of operations—that is, the specific path the transparency wave takes—matters a great deal too. Take something like WikiLeaks. The basic idea was to make transparent the doings of various government agencies. One of the critical political/legal/social questions there was what became transparent first: all the bad things the US government was doing? Or the fact that Assange was assaulting various Swedish groupies? The sequence in which things become transparent is very important. Some version of this probably applies in all cases.

I agree with Posner that transparency often has a corrosive undermining effect. Existing institutions aren’t geared for it. I do suspect that people’s behavior still responds to incentives in some ways, even if there is no free will in the philosophical, counterfactual sense of the word. But I am sympathetic to part of the free will argument because, if you say that free will exists, you’re essentially saying two things:

1.the cause of your behavior came from within you, i.e. you were an unmoved mover, and;

2.that you could have done otherwise, in a counterfactual world.

But if you combine those two claims, the resulting world seems strange and implausible.

Practically, free will arguments are worth scrutiny. Ask yourself: in criminal law, which side makes arguments about free will? Invariably the answer is the prosecution. The line goes: “You killed this person. It was your decision to do that. You’re not even deformed; that’s an extrinsic factor. Rather, you are intrinsically evil.” Anyone who is skeptical about excessive prosecution should probably be skeptical about free will in law. But it makes sense to be less skeptical about it as a philosophical matter.

Question from the audience: There’s the AI joke that says that cars aren’t really autonomous until you order them to go to work and they go to the beach instead. What do you think about the future of encoding free will into computers? Can we imagine mens rea in a machine.

Peter Thiel: In practice it’s most useful to think of questions about free will as political questions. People bring up free will when they want to blame other people.

Theoretically, the nexus between free will and AI does raise interesting questions. If you turn the computer off, are you killing it? There are many different versions of this. My intuition is that we’re really bad at answering these questions. Common sense doesn’t really work; it’s likely to be so off that it’s just not helpful at all. This stuff may just be too weird to figure out in advance. Maybe the biggest lesson is that we should just be skeptical of our intuitions. So I’ll be skeptical of my intuitions, and will not answer your question.

Besides, the easier things are the near term things. Short of full-blown AI, we can automate certain processes and reap large efficiency gains while also avoiding qualms about about turning the computers off at night. We should not conflate super intelligent computers with very good, but still dumber-than-human computers that do things for us. In the near term, we should welcome transparency and automation in our political and legal structures because this will force us to confront present injustices. The fear that all this leads to a Kafkaesque future isn’t illegitimate, but it’s still very speculative.

Question from the audience: How could you ever design a system that responds unpredictably? A cat or gorilla responds to stimulus unpredictably. But computers respond predictably.

Peter Thiel: There are a lot of ways in which computers already respond unpredictably. Microsoft Windows crashes unpredictably. Chess computers make unpredictable moves. These systems are deterministic, of course, in that they’ve been programed. But often it’s not at all clear to their users what they’ll actually do. What move will Deep Blue make next? Practically speaking, we don know. What we do know is that the computer will play chess.

It’s harder if you have a computer that is smarter than humans. This becomes almost a theological question. If God always answers your prayers when you pray, maybe it’s not really God; maybe it’s a super intelligent computer that is working in a completely determinate way.

Question from the audience: One problem with transparency is that it can delegitimize otherwise legitimate authority. For instance, anyone can blog and post inaccurate or harmful information, and the noise drowns out more legitimate information. Couldn’t more transparency in the legal system actually be harmful because it would empower incorrect or illegitimate arguments?

Peter Thiel: This question gets at why it’s important to have an incremental process towards full transparency instead a radical shift. There are certainly various countercurrents that could emerge.

But generally speaking the information age has tended to result in more homogenization of thought, not less. It just doesn’t seem true that transparency has enabled more isolated communities of belief to disingenuously tap into various shreds of data and thereby maintain edifice where they couldn’t have before. It’s probably harder to start a cult today than it was in the ‘60s or ‘70s. Even though you have more data to piece together, your theory would get undermined and attacked from all angles. People wouldn’t buy it. So the big risk isn’t that excessively weird beliefs are sustained, but rather that we end up with one homogenized belief structure under which people mistakenly assume that all truth is known and there’s nothing left to figure out. This is hard to prove, of course. It’s perhaps the classic Internet debate. But generally the Internet probably makes people more alike than different. Think about the self-censorship angle. If everything you say is permanently archived forever, you’re likely to be more careful with your speech. My biggest worry about transparency is that it narrows the range of acceptable debate.

Question from the audience: How important is empathy in law? Human Rights Watch just released a report about fully autonomous robot military drones that actually make all the targeting decisions that humans are currently making. This seems like a pretty ominous development.

Peter Thiel: Briefly recapping my thesis here should help us approach this question. My general bias is pro-computer, pro-AI, and pro-transparency, with reservations here and there. In the main, our legal system deviates from a rational system not in a superrational way—i.e. empathy leading to otherwise unobtainable truth—but rather in subrational way, where people are angry and act unjustly.

If you could have a system with zero empathy but also zero hate, that would probably be a large improvement over the status quo.

Regarding your example of automated killing in war contexts—that’s certainly very jarring. One can see a lot of problems with it. But the fundamental problem is not the machines are killing people without feeling bad about it. The problem is simply that they’re killing people.

Question from the audience: But Human Rights Watch says that the more automated machines will kill more people, because human soldiers and operates sometimes hold back because of emotion and empathy.

Peter Thiel: This sort of opens up a counterfactual debate. Theory would seem to go the other way: more precision in war, such that you kill only actual combatants, results in fewer deaths because there is less collateral damage. Think of the carnage on the front in World War I. Suppose you have 1,000 people getting killed each day, and this continues for 3-4 years straight. Shouldn’t somebody have figured out that this was a bad idea? Why didn’t the people running things put an end to this? These questions suggest that our normal intuitions about war are completely wrong. If you heard that a child was being killed in an adjacent room, your instinct would be to run over and try to stop it. But in war, when many thousands are being killed… well, one sort of wonders how this is even possible. Clearly the normal intuitions don’t work.

One theory is that the politicians and generals who are running things are actually sociopaths who don’t care about the human costs. As we understand more neurobiology, it may come to light that we have a political system in which the people who want and manage to get power are, in fact, sociopaths. You can also get here with a simple syllogism: There’s not much empathy in war. That’s strange because most people have empathy. So it’s very possible that the people making war do not.

So, while it’s obvious that drones killing people in war is very disturbing, it may just be the war that is disturbing, and our intuitions are throwing us off.

Question from the audience: What is your take on building machines that work just like the human brain?

Peter Thiel: If you could model the human brain perfectly, you can probably build a machine version of it. There are all sorts of questions about whether this is possible.

The alternative path, especially in the short term, is smart but not AI-smart computers, like chess computers. We didn’t model the human brain to create these systems. They crunch moves. They play differently and better than humans. But they use the same processes. So most AI that we’ll see, at least first, is likely to be soft AI that’s decidedly non-human.

Question from the audience: But chess computers aren’t even soft AI, right? They are all programmed. If we could just have enough time to crunch the moves and look at the code, we’d know what/s going on, right? So their moves are perfectly predictable.

Peter Thiel: Theoretically, chess computers are predictable. In practice, they aren’t. Arguably it’s the same with humans. We’re all made of atoms. Per quantum mechanics and physics, all our behavior is theoretically predictable. That doesn’t mean you could ever really do it.

Comment from the audience: There’s the anecdote of Kasparov resigning when Deep Blue made a bizarre move that he fatalistically interpreted as a sign that the computer had worked dozens of moves ahead. In reality the move was caused by a bug.

Peter Thiel: Well… I know Kasparov pretty well. There are a lot of things that he’d say happened there…

Question from the audience: I’m concerned about increased transparency not leaving room for tolerable behavior that’s not illegal. What’s your take on that?

Peter Thiel: That we are generally heading toward more transparency on a somewhat unpredictable path is a descriptive claim, not a normative one. This probably can’t be reversed; it’s hard to stop the arc of history. So we have to manage as best we can.

Certain things become harder to do in a more transparent world. Government, for example, might generally work best behind closed doors. Consider the fiscal cliff negotiations. If you said that they had to take place in front of C-SPAN cameras, things might work less well. Of course, it’s possible that they’d work better. But the baseline question is how good or bad the current system is. My view is that it’s actually quite bad, which is why greater transparency is more likely to be good for it.

I spoke with high-ranking official fairly recently about how Facebook is making things more transparent. This person believed that government only works when it’s secret—a “conspiracy against the people, for the people”sort of narrative. His very sincerely held view was that our government essentially stopped working during the Nixon administration, and we haven’t had a functioning government in this country for 40 years. No one can have a strategy. No one can write notes. Everything is recorded and everything becomes a part of history. We can sympathize with this, in that it’s probably very frustrating for officials who are trying to govern. But normatively, perhaps it’s a good thing if we no longer have a functioning government. All it ever really did well was kill people.

If you believe the stories that most people tell—the government is doing public good, and there’s a sense of superhuman rationality to it—transparency will shatter your view. But if you think that our system is incredibly broken and dysfunctional in many ways, transparency forces discussion and retooling. It affords us a chance to end up with a much more tolerant, if very different, world.

Question from the audience: Can you explain what bringing more transparency to government or the legal system would look like? How, specifically, does automating legal system lead to transparency?

Peter Thiel: Transparency can mean lots of things. We must be careful how we use the term. But take the simple example of people taking cell phone pictures of cops arresting people. That would make police-civilian interactions more transparent, in the thinnest sense. Maybe you find out that there are shockingly few procedural violations and that police are really well behaved. If so, this will increase confidence and make a good system even better. Of course, the reality may be that this transparency will expose the violations and arbitrariness in a bad system.

Capital punishment is another example. DNA testing can be seen as adding another layer of transparency to the system. It turns out that something like 20% of people accused of committing a capital crime are wrongly accused. That figure seems extraordinarily high; you’d think that with capital crimes, investigations would be much more serious and thorough and consequently there would be a very low rate of nabbing the wrong person. Today we’re increasingly skeptical of the justice of capital punishment, and for good reason. If the DNA tests had shown that we’ve never ever made an ID mistake in a capital case, we’d probably think very differently about our system.

The general insight is that as you codify things, you tend to bring to the surface what’s actually going on. One of the virtues of a more automated system is that it’s easier to describe accurately. You can actually understand how it works. At least in theory, you bring injustice to light. In practice, you’d then have to change the injustice. And you can’t do that if you don’t know about it.

Question from the audience: Doesn’t transparency to whom matter more than just transparency? Transparency to the programmer re witch-hunting doesn’t expose the existence of witch-hunting to society, right? Should government software be open sourced?

Peter Thiel: I’ll push back on that question a little bit. Just because you have an algorithm doesn’t mean people will always know what it will do—this is the chess computer example again. It’s very possible that people wouldn’t understand some things even with transparency. We have transparency on the U.S. budget, but no one in Congress can actually read or understand it all.

It’s a big mistake to think that one system can be completely transparent to everybody. It’s better to think in terms of many hidden layers that only gradually get uncovered.

Question from the audience: Since there are different countries, there are obviously multiple legal systems that interact, not just one legal system. Is it problematic that we won’t see the same transparency in some systems that we will in others?

Peter Thiel: Again, the push back is that transparency isn’t a unitary concept. The sequencing path is really important. Does the government get more transparency into the people? The people into the government? Government into itself, and the machine just works more efficiently? Depending on just how you sequence it, you can end up with radically different versions.

Look at Twitter and Facebook as the related to the Arab Spring. Which way do these technologies cut in terms of transparency? In 2009, the Iranian government hacked Twitter and used it to identify and locate dissidents. But in Tunisia and Egypt, the numerous protest posts and tweets helped people realize that they weren’t the only ones who were unhappy. The exact same software plays out in extremely different ways depending on the sequencing.

Question from the audience: Is there a point in time where we just shift from current computers to future computers? Or does technological advance follow a gradual spectrum?

Peter Thiel: Maybe there’s a categorical difference at some point. Or maybe it’s just quantitative. It’s conceivable that as some point things are just really, really different. The 20-year story about greater transparency is one where you can make reasonable predictions as to what computers will likely do and what they’re likely to automate, even though the computers themselves will be a little different. But 1,000 years out is much more opaque. Will the computers be just or unjust? We have no good intuition about that. Maybe they’ll be more like God, or we’ll be dealing with something beyond good and evil.

Question from the audience: Traffic cameras are egalitarian. But cops might be racist. Do you think we run the risk of someday having racist or malicious computers?

Peter Thiel: In practice, we can still generally understand computers somewhat better than we can understand people. In the near term at least, more computer automation would produce systems that are more predictable and less arbitrary. There would be less empathy but also less hate.

In the longer term, of course, it could be just the opposite. There may be real problems there. But key to understand is that we’re experiencing an irreversible shift toward greater transparency. This is true whether your time horizon is long-term, where things are mysterious and opaque, or short-term, where things become automized and predictable. Naturally, you have to get to the short-term first. So we should first realize the gains there, and we can figure out any long-term problems later.