Greece Crowns Pentagram Devouring Whole Universe, Says Times (Subtly!)

Moderators: Elvis, DrVolin, Jeff

seemslikeadream posted in the other thread wrote:The Greeks Get It

By Chris Hedges

Here’s to the Greeks. They know what to do when corporations pillage and loot their country. They know what to do when Goldman Sachs and international bankers collude with their power elite to falsify economic data and then make billions betting that the Greek economy will collapse. They know what to do when they are told their pensions, benefits and jobs have to be cut to pay corporate banks, which screwed them in the first place. Call a general strike. Riot. Shut down the city centers. Toss the bastards out. Do not be afraid of the language of class warfare—the rich versus the poor, the oligarchs versus the citizens, the capitalists versus the proletariat. The Greeks, unlike most of us, get it.

The former right-wing government of Greece lied about the size of the country’s budget deficit. It was not 3.7 percent of gross domestic product but 13.6 percent. And it now looks like the economies of Spain, Ireland, Italy and Portugal are as bad as Greece’s, which is why the euro has lost 20 percent of its value in the last few months. The few hundred billion in bailouts for other faltering European states, like our own bailouts, have only forestalled disaster. This is why the U.S. stock exchange is in free fall and gold is rocketing upward. American banks do not have heavy exposure in Greece, but Greece, as most economists concede, is only the start. Wall Street is deeply invested in other European states, and when the unraveling begins the foundations of our own economy will rumble and crack as loudly as the collapse in Athens. The corporate overlords will demand that we too impose draconian controls and cuts or see credit evaporate. They have the money and the power to hurt us. There will be more unemployment, more personal and commercial bankruptcies, more foreclosures and more human misery. And the corporate state, despite this suffering, will continue to plunge us deeper into debt to make war. It will use fear to keep us passive. We are being consumed from the inside out. Our economy is as rotten as the economy in Greece. We too borrow billions a day to stay afloat. We too have staggering deficits, which can never be repaid. Heed the dire rhetoric of European leaders.

“The euro is in danger,” German Chancellor Angela Merkel

told lawmakers last week as she called on them to approve Germany’s portion of the bailout plan. “If we do not avert this danger, then the consequences for Europe are incalculable, and then the consequences beyond Europe are incalculable.”

Beyond Europe means us. The right-wing government of Kostas Karamanlis, which preceded the current government of George Papandreou, did what the Republicans did under George W. Bush. They looted taxpayer funds to enrich their corporate masters and bankrupt the country. They stole hundreds of millions of dollars from individual retirement and pension accounts slowly built up over years by citizens who had been honest and industrious. They used mass propaganda to make the population afraid of terrorists and surrender civil liberties, including habeas corpus. And while Bush and Karamanlis, along with the corporate criminal class they abetted, live in unparalleled luxury, ordinary working men and women are told they must endure even more pain and suffering to make amends. It is feudal rape. And there has to be a point when even the American public—which still believes the fairy tale that personal will power and positive thinking will lead to success—will realize it has been had.

We have seen these austerity measures before. Latin Americans, like the Russians, were forced by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to gut social services, end subsidies on basic goods and food, and decimate the income levels of the middle class—the foundation of democracy—in the name of fiscal responsibility. Small entrepreneurs, especially farmers, were wiped out. State industries were sold off by corrupt government officials to capitalists for a fraction of their value. Utilities and state services were privatized.

Advertisement

What is happening in Greece, what will happen in Spain and Portugal, what is starting to happen here in states such as California, is the work of a global, white-collar criminal class. No government, including our own, will defy them. It is up to us. Barack Obama is simply the latest face that masks the corporate state. His administration serves corporate interests, not ours. Obama, like Goldman Sachs or Citibank, does not want the public to see how the Federal Reserve Bank acts as a private account and ATM machine for Wall Street at our expense. He, too, has helped orchestrate the largest transference of wealth upward in American history. He serves our imperial wars, refuses to restore civil liberties, and has not tamed our crippling deficits. His administration gutted regulatory agencies that permitted BP to turn the Gulf of Mexico into a toxic swamp. The refusal of Obama to intervene in a meaningful way to save the gulf’s ecosystem and curtail the abuses of the natural gas and oil corporations is not an accident. He knows where power lies. BP and its employees handed more than $3.5 million to federal candidates over the past 20 years, with the largest chunk of their money going to Obama, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

We are facing the collapse of the world’s financial system. It is the end of globalization. And in these final moments the rich are trying to get all they can while there is still time. The fusion of corporatism, militarism and internal and external intelligence agencies—much of their work done by private contractors—has given these corporations terrifying mechanisms of control. Think of it, as the Greeks do, as a species of foreign occupation. Think of the Greek riots as a struggle for liberation.

Dwight Macdonald laid out the consequences of a culture such as ours, where the waging of war was “the normal mode of existence.” The concept of perpetual war, which eluded the theorists behind the 19th and early 20th century reform and social movements, including Karl Marx, has left social reformers unable to deal with this effective mechanism of mass control. The old reformists had limited their focus to internal class struggle and, as Macdonald noted, never worked out “an adequate theory of the political significance of war.” Until that gap is filled, Macdonald warned, “modern socialism will continue to have a somewhat academic flavor.”

Macdonald detailed in his 1946 essay “The Root Is Man” the marriage between capitalism and permanent war. He despaired of an effective resistance until the permanent war economy, and the mentality that went with it, was defeated. Macdonald, who was an anarchist, saw that the Marxists and the liberal class in Western democracies had both mistakenly placed their faith for human progress in the goodness of the state. This faith, he noted, was a huge error. The state, whether in the capitalist United States or the communist Soviet Union, eventually devoured its children. And it did this by using the organs of mass propaganda to keep its populations afraid and in a state of endless war. It did this by insisting that human beings be sacrificed before the sacred idol of the market or the utopian worker’s paradise. The war state provides a constant stream of enemies, whether the German Hun, the Bolshevik, the Nazi, the Soviet agent or the Islamic terrorist. Fear and war, Macdonald understood, was the mechanism that let oligarchs pillage in the name of national security.

“Modern totalitarianism can integrate the masses so completely into the political structure, through terror and propaganda, that they become the architects of their own enslavement,” he wrote. “This does not make the slavery less, but on the contrary more— a paradox there is no space to unravel here. Bureaucratic collectivism, not capitalism, is the most dangerous future enemy of socialism.”

Advertisement

Macdonald argued that democratic states had to dismantle the permanent war economy and the propaganda that came with it. They had to act and govern according to the non-historical and more esoteric values of truth, justice, equality and empathy. Our liberal class, from the church and the university to the press and the Democratic Party, by paying homage to the practical dictates required by hollow statecraft and legislation, has lost its moral voice. Liberals serve false gods. The belief in progress through war, science, technology and consumption has been used to justify the trampling of these non-historical values. And the blind acceptance of the dictates of globalization, the tragic and false belief that globalization is a form of inevitable progress, is perhaps the quintessential illustration of Macdonald’s point. The choice is not between the needs of the market and human beings. There should be no choice. And until we break free from serving the fiction of human progress, whether that comes in the form of corporate capitalism or any other utopian vision, we will continue to emasculate ourselves and perpetuate needless human misery. As the crowds of strikers in Athens understand, it is not the banks that are important but the people who raise children, build communities and sustain life. And when a government forgets whom it serves and why it exists, it must be replaced.

“The Progressive makes History the center of his ideology,” Macdonald wrote in “The Root Is Man.” “The Radical puts Man there. The Progressive’s attitude is optimistic both about human nature (which he thinks is good, hence all that is needed is to change institutions so as to give this goodness a chance to work) and about the possibility of understanding history through scientific method. The Radical is, if not exactly pessimistic, at least more sensitive to the dual nature; he is skeptical about the ability of science to explain things beyond a certain point; he is aware of the tragic element in man’s fate not only today but in any collective terms (the interests of Society or the Working Class); the Radical stresses the individual conscience and sensibility. The Progressive starts off from what is actually happening; the Radical starts off from what he wants to happen. The former must have the feeling that History is ‘on his side.’ The latter goes along the road pointed out by his own individual conscience; if History is going his way, too, he is pleased; but he is quite stubborn about following ‘what ought to be’ rather than ‘what is.’

“The claim made in the IMF documents is that the “program” (including the inhuman austerity conditions and targets) is “achievable”, “feasible” and “sustainable”. On this point, however, the IMF of course has not been able to convince some of the most prominent economists and commentators (Krugman, Feldstein, Stiglitz, Rogoff, Eichengreen, Johnson, Roubini, Rodnik, Buiter, Reinhart, Fitoussi, Wyplosz, Wolf, Munchau, among others, mentioned here in no particular order.) All are saying in one way or another that the numbers do not add up. In other words, the arithmetic shows that even with this IMF/EU package, the Greek debt is not sustainable. (See in particular Buiter’s latest 65-page research report ‘Sovereign Debt Problems in Advanced Industrial Countries’.)”

SPIEGEL: The German government has said that there was no alternative to the rescue package for Greece, nor to that for other debt-laden countries.

Pöhl: I don't believe that. Of course there were alternatives. For instance, never having allowed Greece to become part of the euro zone in the first place.

SPIEGEL: That may be true. But that was a mistake made years ago.

Pöhl: All the same, it was a mistake. That much is completely clear. I would also have expected the (European) Commission and the ECB to intervene far earlier. They must have realized that a small, indeed a tiny, country like Greece, one with no industrial base, would never be in a position to pay back €300 billion worth of debt.

SPIEGEL: According to the rescue plan, it's actually €350 billion ...

Pöhl: ... which that country has even less chance of paying back. Without a "haircut," a partial debt waiver, it cannot and will not ever happen. So why not immediately? That would have been one alternative. The European Union should have declared half a year ago -- or even earlier -- that Greek debt needed restructuring.

SPIEGEL: But according to Chancellor Angela Merkel, that would have led to a domino effect, with repercussions for other European states facing debt crises of their own.

Pöhl: I do not believe that. I think it was about something altogether different.

SPIEGEL: Such as?

Pöhl: It was about protecting German banks, but especially the French banks, from debt write offs. On the day that the rescue package was agreed on, shares of French banks rose by up to 24 percent. Looking at that, you can see what this was really about -- namely, rescuing the banks and the rich Greeks.

SPIEGEL: In the current crisis situation, and with all the turbulence in the markets, has there really been any opportunity to share the costs of the rescue plan with creditors?

Pöhl: I believe so. They could have slashed the debts by one-third. The banks would then have had to write off a third of their securities.

SPIEGEL: There was fear that investors would not have touched Greek government bonds for years, nor would they have touched the bonds of any other southern European countries.

Pöhl: I believe the opposite would have happened. Investors would quickly have seen that Greece could get a handle on its debt problems. And for that reason, trust would quickly have been restored. But that moment has passed. Now we have this mess.

Truths and Myths about the "Greek Crisis"

18 May

The following is a guest post by Polyvios Petropoulos, a former university professor of economics and management in the US.

Petropoulos contends that the austerity package drawn up by the IMF is not credible and that everyone knows Greece cannot meet its commitments. He ends the post with a four-step scenario he deems actually plausible.

Petropoulos’ view differs considerably from the usual fare at Credit Writedowns. However, his is a good alternate view of the Greek situation from a Greek perspective. Pay particular note to his assertions about government salaries and the credibility of government finances in Greece and elsewhere.

Zeus (Dias), the Greek god, gave Europe the name of his beloved woman (Europa), hoping that she would be immortal. The question now is: Will the European dream end where it began, in Greece, or will it end in catharsis, as all Greek tragedies do?

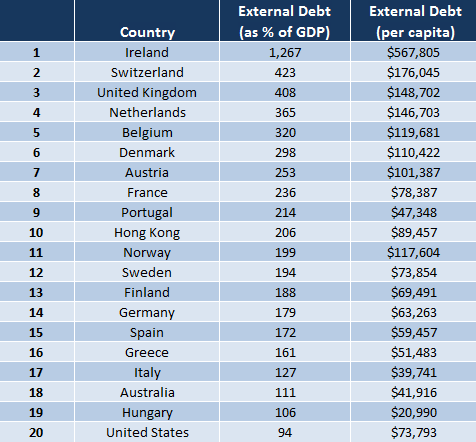

It is only in the last few months that most commentators realized that this crisis is not about Greece only, that it is a European and, eventually, a global sovereign debt crisis, and that Greece is not even the worst case. Anyone who still thinks that this is only a Greek (or a GIPS) crisis should take a look at this table,

http://seekingalpha.com/article/188776- ... ook-so-bad

published three months ago, which shows that Greece is only 16th in external debt as % of GDP among developed countries, whereas Germany is 14th, with a slightly higher figure, believe it or not, France is 8th, and the UK is 3rd . As to structural deficit-to-GDP, it is higher in the US (7.8%) and the UK (7.6%) than it is in Greece (6.1%). See here.

https://ems.gluskinsheff.net/Articles/B ... 030410.pdf

Have the Greeks been “fiddling” with their statistics? Maybe they did. But we should also realize that no budget figures of any country can be dependable, credible, or comparable, and furthermore figures are easy to play with, as there are no standard, uniform, accounting rules for country budgets, and no surveillance whatsoever. Let me elaborate: Do the figures of any country include off-budget items, unfunded and contingent liabilities, future or deferred commitments, government guarantees, bank-insurance schemes, the debt/liabilities of public corporations, pension schemes and health systems? What about leasing and lease-backs? Are “top secret” expenditures for defence and intelligence activities included and shown in government budgets? Are expenditures presented when contracts are signed or when they will be paid for? Are revenues brought forward by factoring etc.?

What about swaps, securitisation and other gimmicks used to fiddle with the figures? Let’s look at the allegation that Greece used cross currency swaps to reduce its debt, and whether it is the only country that has used them. First of all, “swaps” and other “instruments of mass destruction” were not invented in Greece or promoted by Greeks. Secondly, the GS swap deal was not done before but after Greece had joined the EMU (in 2002). Thirdly, such swaps were at the time acceptable by the EU commission and the Eurostat, as the EU commission spokesman Amadeu Altafa declared in Brussels on Feb. 15th. Which other countries have used or were involved in swaps? Too many to even list them here, let alone to describe the boring details of the exact deals of each: Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, Belgium, UK, and Germany (yes), among others. Even Mr. Bernanke, in his testimony before the Committee on Financial Services on Feb. 10th, says that the Fed “entered into temporary currency swap agreements” and has used “reverse repos”.

A lot has been written about corruption in Greece. And surely there is corruption in Greece, as there is everywhere. I tried the Google search engine a few days ago, and typed “corruption in…(country)”. I got 28,600,000 links for the US, 8,930,000 for France, 8,490,000 for the UK, 6,910,000 for Germany, 4,720,000 for Italy and 2,680,000 for Greece. You may say that this is not necessary indicative and dependable about the amount of corruption in the different countries, but neither are the rankings of “Transparency International”. According to an opinion survey conducted in Nov. 2009 by the Eurobarometer, 78% of Europeans say that “corruption is a major problem in the EU”. A “fakelaki” in Greece is a sort of a tip in most cases. Like the “tip” you may give to the traffic policeman in some countries…(you know which one I mean) to avoid getting a traffic ticket (don’t ever try it in Greece by the way). Now, other more serious types of corruption, such as bribing, are also prevalent in Greece, primarily in tax revenue depts. Many foreign companies (particularly German) bribe Greek officials to get contracts. And I‘ll remind my German friends that it takes two to tango. A lot has been written about other types of corruption in major countries of the western world, such as campaign contributions, sponsoring, lobbying and regulatory agencies staffed by ex-managers of the organizations they are supposed to regulate. Does it remind you of anything?

Who is to blame? “Everyone is a sinner”, according to J. Stark, the ECB chief economist. I have also elaborated who some of the sinners are in this article. But the main sinners of course are the successive Greek governments. It is true that fiscal discipline has been lax. Steps to reduce the budget deficit should have been taken in the “good times”, i.e. in the years before the beginning of the Great Recession. Then, when the recession hit the country in 2007-8, stimulus measures were needed to prop up the economy, but they were not taken, perhaps because the country could not afford them. And now, in 2010, fiscal stabilization has to be carried out. Unfortunately, populist politicians did not realize what was happening or what they should be doing all these years, and they didn’t understand what the correct timing of each phase of economic policy should have been, and they did nothing to increase competitiveness, which is at the root of the problems. It was an unnecessary extravagance for Greece to organize the Olympic Games in 2004, at a cost that exceeded 10 b. euros. And Greece has a defense budget which is roughly one third of its deficit, primarily due to Turkish provocations in the Aegean Sea. One word to the supporters of speculators and naked CDSs: Nobody is saying that they have created the crisis, as most of them are trying to disprove. What sensible people are saying is that they are exacerbating the crisis.

Have the Greeks been living beyond their means? Here is the answer:

Average salaries in Greece are about 73% of the average eurozone salary. According to Eurostat and GSEE data, 60% of Greek pensioners receive less than 600 euros per mo. And 85% receive below 1050 euros per mo. Greek pensions are about 55% of the average eurozone pension, despite inaccurate claims about pensions made in the international media. The usual age for retirement of most people in Greece has been 65 yrs, except for some very special cases in the public sector, which are now being revised upwards –and rightly so- with a new pensions law.

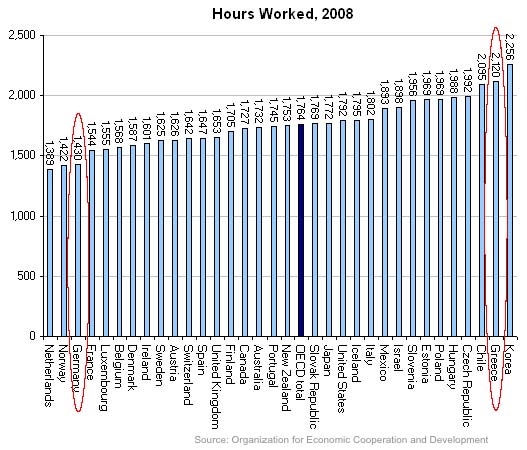

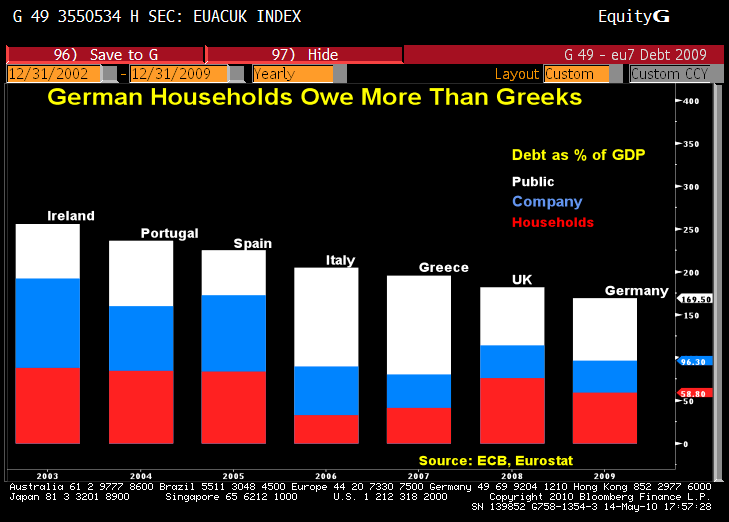

Do Greek households spend more than they earn by borrowing a lot? No. In fact, German households owe more than Greeks. See here. Are Greeks not as hard-working as Germans, or others, as some are saying? Here are the facts. As you can see, Greeks are the most hard-working people in the OECD countries (with the exception of Koreans). The average Greek worker works 2120 hours per year – 690 more than a German worker. (Source: OECD).

Now let me turn to the IMF/EU package concluded with Greece recently. In a press conference published on the IMF website on May 9th, you may read (all bolds are mine):

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sur ... 50910a.htm“Today, the IMF has demonstrated its commitment to doing what it can to help Greece and its people,” Strauss-Kahn said. “The road ahead will be difficult, but the government has designed a credible program that is economically well-balanced, socially well-balanced—with protection for the most vulnerable groups—and achievable. Implementation is now the key.”

Let me consider these claims one by one and be absolutely clear and precise:

First of all, the IMF/EU program (particularly the EU portion) is no “help” or “aid” or “rescue”, or even “bailout”, as the IMF, the EU and various commentators are saying. It consists of a series of loans, in fact non-concessional loans, as it is clearly stated in the Q&A session of the IMF here, with unprecedented draconian conditionality and the normal interest rate which is charged by the IMF in all cases. As to the EU portion, it is given at an even higher interest rate, which should be turned down by the Greek government. Paying 5-6% interest rate, when the country’s GDP growth is -4% p.a., clearly makes the country’s debt problem unsustainable, as has been shown by several economists. In judging interest rates, it should also be remembered that these loans are senior to all other Greek debt.

Second, it was not offered to help the “Greek people”. It was offered to help the bondholders, the bankers, the euro, and to avoid contagion with its nasty consequences for the EU and the global economy, as it is clearly stated elsewhere in the Q&A session mentioned above.

Third, there is absolutely no “protection for the most vulnerable”, as one would have expected from the “socialist” (or “ex-socialist”?) head of the IMF, or the “socialist” Greek government for that matter, and this claim is made several times in both of the documents mentioned above. The opposite is true. A mere listing of some of the austerity measures will suffice to prove my assertion:

-A meager so-called “social solidarity allowance” for destitute people was abolished, despite assurances in the IMF Q&A session that “the targeting of social expenditures will be revised to strengthen the social safety net for the most vulnerable”.

-Despite assurances in the Q&A session that “minimum pensions and family support instruments will not be cut”,all public and private-sector pensions and allowances have been cut, all the way down to meager pensions of 450, 500, 550 euros per month etc., which are well below the poverty line (making it impossible for old pensioners to survive), and this is what the majority of pensioners receive. This must be reversed for both human and economic reasons. On the other hand, nothing has been changed regarding the 300 Greek MPs, who receive a substantial pension after only 8 yrs in parliament!

-Reduction of the salaries of even the lowest-paid civil servants. The 13th and 14th bonuses, which are often mentioned as a sign of extravagance, should have been incorporated in the 12 monthly salaries, and Greek salaries would still be lower then the EU average. (See comparison of total Greek and EU salaries above.)

-Freezing of the lowest salaries and pensions for the next few years, although inflation is already galloping above 4% p.a., well above the EU average, and may go even higher, despite the IMF claim at the press conference that“inflation is expected to remain below the euro average.”

-VAT (value added tax), which was much higher in Greece than in Portugal and Spain, was raised by about 20% on all goods, including basic foodstuffs, which make up the majority of poor people’s purchases.

-Sales taxes were raised on –supposedly- luxury goods…such as gasoline (+50%), cigarettes, beer, wine etc. I say to the poor people of Greece: For heaven’s sake, don’t drive, and stay away from all these sinful products!

To be fair, according to an interview of Mr. Papaconstantinou, the Greek finance minister, a few days ago, the reduction of the pitiful pensions of the private sector was not imposed by the IMF officials in Athens, but by the EU officials. My guess is that it must have been decided at the insistence of an official appointed to the negotiating team by “Frau Nein”, who wants blood, sweat and tears imposed on the Greek people.

The agreement reached between the IMF, the EU and the Greek government says nothing about reducing the number of MPs and ministries, or the number of civil servants, says nothing about capital gains, about selling part of the real estate owned by the state and the church, and is vague about taxing the rich, reducing drastically the state’s expenses, making politicians accountable for corruption with strict laws, about privatizations, competitiveness and export-led growth. Greeks should be allowed to bring their deposits (over 200bn) back from abroad without the 5% penalty. Housing construction, which is the economy’s “steam engine”, was further penalized. Labor market reforms should have been more daring. For obvious reasons, nothing has been announced by the Greek government about the sensitive subject of military expenditures, although the IMF says that they will be reduced. I assume that Greeks will require proportional reductions from Turkey before actually implementing such reductions. Also Greece’s EU partners, from whom Greece buys most of the weapons, will not be thrilled about this. Nothing was said also about the great oil reserves waiting to be drawn from the Aegean Sea, worth several trillions. Implementation of the measures announced is also questionable. It’s indicative that dates by which income tax returns for 2009 must be submitted were again postponed recently until as late as May-June of this year. In the meantime the tax people are looking for swimming pools in the backyards of the Greeks, as if this were a sign of great wealth…

Regarding competitiveness, which is indeed of paramount importance, the IMF makes simplistic observations, as is the case with many other commentators. First of all, competitiveness is not only a question of unit labor costs, but depends on many other factors as well. Secondly, looking only at the comparative percentage increase of unit labor costs in Greece since 1999, as most do, is not enough, because absolute figures of wages and salaries, which are much lower compared to the EU average, as I have shown above, do matter as well, and are not mentioned in any of the IMF documents, or by the media. ULCs in absolute figures are lower in Greece than in any of the other GIIPS countries, as well as in the UK and Denmark.

Finally, nothing is said about the intra-EU imbalances, or about the divergences in competitiveness, trade balances and inflation, which were created in favor of the core EU countries of the north vis-à-vis the southern peripherals since 1999, as a result of the common market and pegged currency, as economic theory postulates that they are bound to.

Will the “program” work? The claim made in the IMF documents is that the “program” (including the inhuman austerity conditions and targets) is “achievable”, “feasible” and “sustainable”. On this point, however, the IMF of course has not been able to convince some of the most prominent economists and commentators (Krugman, Feldstein, Stiglitz, Rogoff, Eichengreen, Johnson, Roubini, Rodnik, Buiter, Reinhart, Fitoussi, Wyplosz, Wolf, Munchau, among others, mentioned here in no particular order.) All are saying in one way or another that the numbers do not add up. In other words, the arithmetic shows that even with this IMF/EU package, the Greek debt is not sustainable. (See in particular Buiter’s latest 65-page research report “Sovereign Debt Problems in Advanced Industrial Countries”.)

Nor did the IMF convince the markets with this package. In fact, I am beginning to believe that nothing will convince them.

Even though there was initially some improvement, not because of the IMF/EU package for Greece, but after the latest eurozone stabilization program of nearly one trillion, the latest ECB decision to in effect monetize the debt by buying government bonds (as all other central banks have been doing all along), the USD loan swaps, the laxity by the ECB with respect to accepting government bonds of a lower rating as collateral, and the plans to establish an EU rating agency, which were all announced very recently. Other factors which may, or may not, impress the markets are the imminent eurozone decisions regarding economic coordination and governance (see the EU commission proposals at http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/art ... 2-com(2010)250_final.pdf), and the impressive -40% reduction of the Greek deficit in the first quarter of this year.

Despite the theories of some ivory-tower economists, about the supposed “rationality”, “discipline” and “efficiency” of the markets, markets and speculators are not at all rational. Greece is not alone in the debt trap, not even the worst case, to be penalized by the markets so harshly. Recent EU figures show that total debt is 224pc of GDP in Greece, 272pc in Spain and 331pc in Portugal. Also the gross external debt of Greece is 168.2pc of GDP, Portugal’s is 232.7pc and Spain’s is the same as Greece’s (Ireland’s is a record 979.4pc). But the spreads on 10-yr debt were recently 7.75pc for Greece (after dropping from previous incredible heights), and only 3.92pc for Spain and 4.62pc for Portugal. Does this make any sense? And yet I do not wish to be overly suspicious or conspiratorial…

On “restructuring” or “rescheduling” of Greek debt, the IMF is adamant in both documents: No way. Again many of the economists previously mentioned are not at all convinced. The discussion which is now going on is whether to restructure with or without a haircut, or to do a “voluntary” rescheduling, as I have suggested as Option C here, and whether this should be done sooner or later, with or without IMF’s and eurozone’s consent, without a euro exit or with euro exit and drachma devaluation. Discussions of the Greek government with Lazard, the investment bank who are specialists in debt restructuring, make some people suspicious.

A plausible scenario could be as follows in this sequence of steps: (1) Start receiving IMF/EU funds in tranches, preferably after revising terms and EU interest rate, as I have suggested, and start selling bonds to ECB directly, or through Greek banks. (2) Evaluate progress of implementation and results every month, revising measures where needed. (3) If all goes according to plan, continue implementing. If not, reschedule debt with IMF/EU consent. (4) If no consent given, or, if still no progress is made, then exit eurozone and devalue the drachma.

Proposals for Greece - Let's Change the Discussion

April 29, 2010

Greece should not accept the part of the IMF/EU "package" which is being offered by the EU if the EU does not lower the interest rate to 3%, or at most 3.5%, as that is the maximum rate charged by the IMF. It is as if you can borrow from a stranger at 1.50%-3.50%, and your partner is asking you for 5%. Moreover, the calculations of several economists with respect to the so-called "snowball effect" indicate that if Greece borrows at a rate of 5% or more, her debt as a % of GDP becomes unsustainable. The interest rate, as has been shown by a number of economists, should be lower than the growth rate of GDP, and of course a Greek GDP growth above 5% is not very probable in the near future.

Apparently, the Greek government could have not waited to activate the so-called "bailout mechanism" (although “lending” is in my view a more precise description, rather than bailout) after the German elections on May 9th, which would have been preferable for obvious reasons. Greece should initially ask the IMF for its part of the lending (and anyone else who can lend her at the same rate as the IMF), and she should then ask Germany for its share (and other countries which must have the approval of their parliament) after May 9th. Greece should not give in easily to "Frau Nein" regarding the interest rate. This is a "poker" game played by this lady and her sympathizers (Axel Weber, Otmar Issing, etc.), but Greece also has a strong "hand": Somebody has said that if you owe a little bit of money, you have a problem. If you owe a lot, your lenders have the problem. One issue is of course the risk of contagion of the initial crisis, which will probably spread to other peripheral countries of the eurozone (I prefer calling them GISPIs), and then all across the eurozone, and eventually throughout the world, because –as it is now well understood- Greece is not the only country that has a large deficit and public debt. Another issue is the financial damage which will be suffered by German banks (among others) by a possible restructuring of Greek debt, and their bailout cost for the German government will be huge, much larger than the requested loan to Greece. Not to mention the threat of leaving the euro, returning to the drachma, currency depreciation, default, etc. The Greek Prime Minister should put these “guns” on the table, even if he does not intend to use them.

I do not wish to dwell at length on the responsibility of Germany (and the entire eurozone) for the rapid deterioration of the Greek crisis, the rise in spreads, the panic in the markets and the party of the speculators. Greece should remind her partners of the structural failures of the EU and the eurozone, the intra-European imbalances (for example, for Germany to export and to have a smaller deficit than Greece’s the Greeks should import their products and have a greater deficit as a result) and, finally, it is a well-established fact in economics that in a monetary-trade union most economic variables (such as exports, competitiveness, deficits, debt, etc.) of the countries in the union are bound to diverge over the years. Strong countries will get stronger and the weak weaker. Thus, the necessary solidarity is not a good-Christian-act, but an unavoidable necessity for maintaining the union. Nor should Greece let the Europeans forget that she has made two gifts to the eurozone: she has contributed to the depreciation of the euro, making eurozone exports cheaper, and she has helped EU leaders realize what leading economists have been saying for years, namely that a monetary union without common economic-fiscal policies and without solidarity cannot exist.

Those Greeks who demonize the IMF offer a poor service to their country. IMF is not a "bogeyman". And indeed, as proclaimed by well-known economists and former IMF officials (such as K. Rogoff, S. Johnson, etc.), the IMF has been offering loans on softer terms in recent years. See e.g. conditions imposed by the IMF on Romania and other countries. But one thing is certain: Greece should not accept the imposition of additional austerity measures for 2010, as “Frau Nein” has recently suggested. For 2011 and 2012, it’s a different story. It will depend on the results of the severe austerity measures already taken, which should be apparent by the end of 2010. Unfortunately, it is true that these harsh measures have not yet been applied with the rigor and speed they should have. And of course a deficit below 3% of GDP by 2012, when this threshold has now been exceeded even by Germany, is almost impossible for Greece to achieve, without strangling the economy of the country and its people, and should not have been promised.

However some steps to liberalize the labour market should not be taboo, particularly as the current restrictions are not being complied with in practice in most cases, nor can they be policed. On the contrary, such measures as freedom to fire employees with no restrictions and the abolition of a minimum wage-salary will improve the competitiveness of Greek firms and the economy (by reducing the average labour cost per unit of output), which is at the root of the Greek crisis, and will increase employment as well, as surely no government can possibly reduce wages in the private sector by decree, as some people are suggesting. But the government should indeed slash drastically expenditures of the sinful and bloated public sector. And Greece does not need more than 10 ministries at most. Also, if Greece sells half of the public properties (and I am not talking here about islands or monuments, as some Germans have suggested…), the country may pay off a third of its debt. Growth and economic export-oriented development should not be forgotten, because obviously it affects the denominator of the two fractions of deficit/GDP and debt/GDP. Regarding the numerator of the first fraction, which is revenue minus expenditures, the difficulty of course is to reduce those expenditures and to increase those revenues, which do not reduce private consumption and investment. Without going into a theoretical discussion here, this is related to the “negative multipliers” in some cases. And of course, people with low salaries and pensions should not be burdened further. Privatizations and other structural measures are also urgently needed. If the government does not watch out for these issues, then the economy will enter into the well-known vicious spiral. And I am afraid this is what the recent tax bill may do, which although it may well be in the right direction, some adjustments are needed (which of course I cannot deal with here).

Unfortunately, proposals such as the creation of a European Monetary Fund, or Insurance Fund, or the issuing of European bonds, etc. have not been adopted yet, due to indecision and lack of solidarity on the part of certain European leaders. However, there are other funding options that Greece could also consider:

Option A: The Greek government may issue bonds at a reasonable interest rate. They will be offered to Greek banks, and the banks will deposit them as collateral at the European Central Bank, withdrawing from the ECB inexpensive cash with which they will then pay the Greek government for the bonds.

Option B: The Greek government can issue bonds in Yen (which are of course convertible into any other currency) to be guaranteed by the JBIC (Japan Bank for International Cooperation), at a low interest rate, as dozens of countries have done, including Turkey.

Option C: As a last resort, there is the possibility of voluntary rescheduling of Greek debt, thus moving the loans, which expire in the short term, further away in time. This is NOT equivalent to default, as some commentators have suggested. In fact, a well-known UK bank has done this, without any problem.

Finally, the Greek government should deal with the vicious orchestrated attacks by certain international media and their paid commentators, the various lobbies and politicians, handsomely compensated by investment “banksters” who work together with some hedge funds, their blogs and think tanks, and those credit rating agencies that are being paid by companies and countries being evaluated by them. The lies and half-truths about Greece published daily are incredible, and they certainly add to the panic in the markets. “Country runs” (like what is now happening to Greece) are similar to “bank runs”. No bank or country can cope under these circumstances. All these inaccuracies should be answered on behalf of the government. (To be clear: I am not denying the responsibilities and mistakes of successive Greek governments, but Greece is not alone in this mess, and Truth should be respected above all.)

Moral deficit - not moral hazard - is at the root of the recent economic recession, which is now gradually becoming a severe sovereign credit crisis of global proportions.

(Old News Dept.)

Greece debt crisis deferred, not cured

Investors have good reason to think Greece's debt crisis has not been solved by the IMF bailout package

Nils Pratley

guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 4 May 2010 21.09 BST

A protester is seen behind a banner during a rally in Athens. Greece's debt crisis may return to haunt it. Photograph: Thanassis Stavrakis/AP

There's a pattern here. European politicians stand up on a Sunday and declare that they have found a solution to Greece's financial crisis. A day or two later, investors respond by shouting "no, you haven't". Today's performance of this drama was the most alarming to date. The €110bn three-year bailout for Greece was meant to be the final word on the matter from the eurozone members and the IMF. It was greeted with big falls in stock markets around the world while the euro hit a 12-month low against the dollar.

Unfortunately, investors have good reasons to think the Greek bailout will succeed only in deferring pain. Even if the Greeks are eventually strong-armed into accepting austerity measures, it is hard to believe the economy can revive sufficiently over the next two or three years to make the public sector debts manageable. Nothing of similar scale has been attempted by a country denied the option of devaluing its currency. The fear of eventual default is not going to go away.

It now looks as if the story of the summer has been laid out – the battle by EU officials to persuade the markets that Greece need not cause contagion in other corners of the eurozone.

Neither Portugal nor Spain has debt problems as deep as those of Greece. But investors, having witnessed the shambolic progress of the Greek talks, want to know if the EU has the stomach to bail out other countries if necessary. Once the question starts to be framed that way, the demand for an answer can prove overwhelming. Lehman Brothers was too big to fail until it wasn't.

It is not too late to believe the plot could take a gentler turn. Portugal and Spain could yet surprise the market by setting out more aggressive savings plans. But they would have more time to assemble their defences if investors were convinced that a belt-and-braces answer had been provided in Greece. When a €110bn emergency package can't even produce a 48-hour rally, events are moving too fast for comfort.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2010

Greece still has a choice

It could abandon the euro and default on the bulk of its debt. After all, it worked for Argentina

George Irvin

guardian.co.uk, Sunday 2 May 2010 20.00 BST

In truth, Greece does have an alternative. Instead of submitting to the ferocious and pro-cyclical conditionality imposed by Germany and the IMF – cutting its budget deficit by 11% over three years in return for a €120bn (£104bn) loan – it could follow Argentina's example in 2001-02, and default on the bulk of its sovereign debt. This would mean abandoning the euro, introducing a "new drachma" and probably devaluing by 50% or more.

Some weeks ago, I had a private exchange about this scenario with Mark Weisbrot of the Centre for Economic Policy Research in Washington. He favoured Argentinian-style default; I did not. But given Angela Merkel's politically motivated foot-dragging, the failure of the European Central Bank to deal with the problem at an earlier stage and the strongly pro-cyclical nature of the cuts required, I am having second thoughts.

Eight years ago, Argentina defaulted on the major part of its sovereign debt and survived quite well. Many economists predicted that Argentina's debt default would result in currency collapse, hyperinflation and even greater economic contraction than it had endured during its 1999-2002 recession. Instead, after the 2001-02 debt default and subsequent devaluation against the dollar (from 1:1 to 3:1), GDP grew at over 8% per annum over the period 2003-2007 and annual inflation fell from over 10% per month in early 2002 to less than 10% per annum. By 2005, Argentina had sufficient reserves to allow President Néstor Kirchner to pay off its remaining $9.8bn (£6.4bn) loan from the IMF in full and discontinue its programme with them.European leaders would do well to read up on the Asian, Russian and Latin American financial crises of 1997-2002. The Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz famously published an open letter citing his reasons for resigning from his post of chief economist at the World Bank. Among his criticisms of the bank and the IMF was the imposition of drastic deflationary measures on Thailand and Korea in 1997, and on Russia in 1998, mainly to protect the balance sheets of private western banks. The conditionality imposed was paid for dearly by cuts in economic and social expenditure thrust on ordinary citizens.

A central lesson of all this is that unless protective action is taken early, a country can rapidly be overpowered by the financial markets. Once traders start betting against a country's bonds or its currency, the herd instinct takes over. Greece's budget deficit is not particularly high by world standards – 13.6% versus 11% in the UK, and 12.3% in the US. But traders perceived its sovereign debt structure as too risky and prophecies of doom became self-fulfilling. There is a further problem. The spending cuts needed to meet the government's deficit target will undermine Greek government revenues. As an economist at London-based Capital Economics put it: "The key risk to its target is that deeper recession will lead to lower tax revenues, offsetting some of the savings that the government expects to make as a result of its fiscal tightening." In short, even though the bailout package has been agreed, the cuts may prove counterproductive and Greek recovery is far from assured.

The ECB could have nipped this crisis in the bud several months ago, both by continuing to accept Greek government bonds as collateral and by quantitative easing. Although the ECB had used quantitative easing to bailout the EU banking system, it refused to do so for Greece. There are clear signs that contagion is spreading to Portugal, and possibly to Spain and Italy. Can the ECB really be counted on in future to prevent the gradual unravelling of the euro?

As the French economist Jean-Paul Fitoussi argued in a recent interview in Libération, even if the Greek crisis is successfully contained for a time by an EU-IMF package, the financial markets will hope to profit by squeezing other European countries. Meanwhile, ordinary Greeks are taking to the streets to protest against further draconian austerity measures, while the EU's political class continues to focus entirely on its narrow domestic interests. Here in Britain, a bemused electorate apparently has not yet woken up to the nature and magnitude of the cuts we will almost certainly suffer as a result of the 2008 bank bailout. Most important, we have not begun to question seriously whether placating the financial markets by means of such cuts is unavoidable. Perhaps it's time to start thinking the unthinkable: namely, that financial markets should be our servants, not our masters.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2010

No, no, no! For growth to happen, the size of government must be cut. Countries with lower government spending have been proven to economically outperform those with higher public spending.

They will end up defaulting anyway. There is no appetite amongst the population to change their way of life. Unfortunately for them this will involve other European countries taking an almighty hit on the outstanding oans which may push their respective economies back down the tubes. The Greeks will be utterly reliant on the tourist industry with the bulk of its customers coming from the EU. If Greece sticks two fingers up to its 'friends' then I would have thought a boycott of Greece as a holiday destination will be one of severalinformal measures that will come to pass to pay them back.

Yes, the monster Greek bailout has arrived. Now what are the Greeks giving/giving up in turn? Not much I'm afraid... Timid measures, they do not even give up on their (in)famous 13th and 14th salaries, there's only a cap on them. A bit of VAT increase on booze/fags, that is all about it. I can hear the Germans mumbling: the Greeks have conned the EU yet again...

There have been one or two articles on CiF painting Germany as the bad guys over the last couple of days but the truth is that it is Germany bailing Greece out and the Germans are the ones with the choice, they could kick Greece out of the Euro and watch as it defaulted on its debts and slid into economic chaos. Germans are perfectly entitled to ask for concessions in return for their help.

[[The above is clueless. Under the treaty terms a country cannot be kicked out of the euro, certainly not by German fiat.]]

Shameful. Defaulting sets an extremely bad example to the people of Europe. If the Guardian "defaulted" on the authors wages at the end of the month I'm sure he wouldn't be so sympathetic towards such actions. There was a time when people were expected to live up to their obligations, obviously that time is over in the Guardian.

Financial markets will always be our masters...your willingness to admit it notwithstanding. It's the same as saying oxygen will always be our master because we need it to live.

The third article by George Irivn, in which Germany is to blame for all this Greek mess. Seriously George, what's the bit you don't understand? If the Greeks defaulted, then the ordinary folk would pack their bags and go and stay with their relatives ... in Germany. Those that stayed behind, would set the rest of the Greek seaside forests on fire to build more luxury homes for the rich. Those nice German tax payer i.e. me, are actually saving the Greeks from a future of doom and gloom ... and yet somehow you continue to believe its all our fault. [sigh] And now, go and write an article about the flight of all the wealthy Greeks to London, where they are buying expensive properties. Go on, I dare you.

[[The problem is that the wealthy Greeks started going to London already somewhere around the time of the Greek Civil War.]]

What a marvellous solution!!!!! No-one has ever thought of it before???? OK, so they defaulkt on debt, drop the Euro, and make enemies hand over fist. In the meantime they carry on retiring at 53. Then they issue bits of paper with the picture of some famous Greek on it, write a nice big number on the bits of paper, and then they try to start trading. So they want to import some foreign goods, say a Japanese car shipment, and they send a big wad of this paper to the supplier in the belief that they share George Irvin's vision of solvency, or charity, or forgiveness. Let me ask you George Irvin, DO YOU TAKE THE JAPANESE FOR COMPLETE IDIOITS???? DO YOU REALLY THINK THAT GREEK TRADING PARTNERS ARE THAT STUPID???

[[And here comes the capper!]]

Proof - were any more needed - that the Greeks will never be suitable custodians for Britain's Elgin Marbles.

PhilipD

2 May 2010, 8:46PM

The problem - which you don't mention - is that any attempt to leave the euro will lead to massive capital flight and the collapse of the Greek banking system. Nobody will keep their money in any Greek institution if they think the Euro will be abandoned. Maybe there would be some way to engineer it (doing it overnight without an announcement?), but I doubt it very much. And if Greece did do so, it could well provoke a similar flight of capital from Portugal and Spain.

While I'm sympathetic to the argument that Greece is being held to completely unrealistic and counterproductive counter cyclical and deflationary policies by the EU and Germany (notable of course that when they needed it, the Germans were quite happy to borrow money to protect their jobs and industries, the painful reality is that there are fundamental structural issues in the Greek economy that will not be cured by leaving the Euro and devaluing. I posted it in Ilana Il Bets article below, but this very detailed analysis of post war Greek economic history by George Alogoskofis is well worth reading. It makes a convincing argument that while Greece grew very well up to the 1970's (ironically, under an authoritarian government), there has been a gradual loss of competitiveness and growth under both left and right wing governments for the last 30 years - this predates the Euro and can't be blamed on it, although it probably exacerbated existing problems. Greece will not recover until it creates a proper tax system (i.e. one in which people actually pay), and improves domestic productivity. It may be that this crisis will force the government into doing the right thing - just as the Asian crisis persuaded most Asian governments to abandon the Washington Consensus and adopt more mercantilist policies to their benefit.

The answer to the problem is neither the economically illiterate approach of forcing extreme cutbacks onto the Greeks, which seems to be favoured by the Germans and many commentators, nor a highly risky Euro exit and devaluation which might work in the short to medium term, but will just store up long term problems - it is a recognition that it is in all Europes mutual benefit to drive off the speculators, support the Greeks financially, but with external pressure (which many Greeks would welcome) to finally get to grips with the endemic structural problems within the economy.

German roots of Greek crisis remain

The rescue deal may have stopped the financial markets bankrupting Greece but the underlying problem stays unresolved

George Irvin

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 14 April 2010 10.53 BST

On the face of it, the 16 finance ministers of the eurozone countries meeting on 11 April finally put a strong enough aid package on the table to stop the financial markets bankrupting Greece – and apparently to stop contagion from spreading to other indebted Club Med countries. Admittedly, the €30bn deal was done in such a way as to avoid both breaching European Central Bank's (ECB) anti-bailout statutes and burdening German taxpayers; the important thing though is that as a result of the eurozone agreement brokered by the Spanish presidency, Greece has seems to have been saved. Or has it?

Three things are important about the Greek saga. First, the conventional account of the crisis – that a spendthrift Greek government has taken the country to the edge of bankruptcy – is only a small part of the story. Secondly, while the deal buys time, it does not ensure the Club-Med countries against further speculative attack. And thirdly, the true lesson of the story is that it is the Eurozone in general – and Germany in particular – which must put its house in order.

Is Greece broke?

While stories of Greek government nepotism, ludicrously high pensions and the like abound, let us be clear that Greece is not broke. From the mid-1990s until 2009, Greek GDP per head grew faster than the EU average. Its government debt-to-GDP ratio is 113%, yes, but that is not much higher than the OECD debt ratio of 100% projected for 2011 and much less than Japan's 192%.

In essence, what has happened to Greece has happened to most other OECD countries; deep recession has caused a rise in government current transfer expenditure and a precipitous decline in tax receipts. Greece is too small to borrow much domestically, so funding the budgetary gap has meant going to the international market where, fuelled by speculation about debt default, the cost of borrowing has risen to over 7% per annum. Yes, it's true that the previous Greek government attempted to massage the deficit figures with a little help from Goldman Sachs. But Greece's recession-induced budget gap is no different from Britain's.

What is different is that the European Commission wants the budget deficit reduced by 10% of GDP over two years. In the words of Joseph Stiglitz: "With Europe's economy still weak, an excessively rapid tightening of its budget deficit would risk throwing Greece into a deep recession." Anyone in doubt about this principle should look at Ireland where as a result of self-imposed fiscal tightening, GDP in the fourth quarter of 2009 fell by a massive 2.3% (equivalent to 8% annually).

The speculators

"The hedge funds are operating very aggressively," says Hans Redeker, chief currency strategist at French bank BNP Paribas. Few people seem to realise that 95% of Greek sovereign debt is held mainly by European banks within the eurozone. Last year, before the crisis exploded, banks and hedge funds had bought up a large amount of Greek debt cheaply, insuring it by purchasing credit default swaps (CDSs). The crisis has enabled banks to make a killing by selling what is now high-yield Greek debt and issuing further CDSs at a huge premium.

Moreover, the ECB, by pouring liquidity into the European banks, helped spur the Greek debt purchasing spree. As a recent report in the Financial Times put it, a lot of smart traders saw the crisis coming – one only had to look at the amount of sovereign debt the ECB was pushing European banks to buy. The ECB further exacerbated the problem by refusing in future to accept Greek bonds as collateral. And during the two-month period when eurozone ministers have refrained from taking concrete action on the grounds that dallying would "force" the Greeks to clean up their act, these same smart traders have made millions.

Eurozone economic governance

While Greek mismanagement and speculation against Greek bonds are part of the story, the key to understanding the crisis lies not in Greece but in Germany. Germany insisted on a eurozone with a strong monetary authority (the ECB) focused on fighting inflation, but without a "euro treasury" to conduct countercyclical fiscal policy and to effect transfers to countries in need of support – in sharp contrast to arrangements in, say, the US. Germany also continued to pursue a "strong money" policy, promoting export-led growth by means of restraining public spending and private-sector real wage growth, and thus domestic demand. The eurozone version of this policy was the 1997 stability and growth pact requiring eurozone members to keep the budget deficit below 3% and the debt/GDP ratio below 60%.

There are two problems here. First, not all countries can be net exporters like Germany. Two thirds of its exports go to the eurozone, and since one county's exports must be another's imports, the German surplus is reflected by deficits elsewhere; inter alia, the Club Med countries. Second, the eurozone's monetary and fiscal arrangements are inherently deflationary. A balanced budget may be acceptable in "normal times" but it is positively harmful during a global recession. It is notable that current statistical indicators for the eurozone show the recovery weakening, particularly since the ECB in recent weeks has refused to offset tight fiscal policy with further monetary loosening.

In sum, while the deal agreed on 11 April may have stopped financial markets from bidding up Greek government bond yields to dizzying heights, the underlying problem remains unresolved. The current economic architecture of the eurozone puts intolerable deflationary pressure on its most vulnerable members at times of crisis, and if one member should be forced out of the eurozone, contagion could overwhelm many more member states, possibly toppling Europe's most important integration achievement since the creation of the Community in 1957. But Europe's current political leaders remain focussed on their narrow national interests; so far, they have lacked the vision required to chart the new course needed—not just for Greece but for Europe as a whole.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2010

From Latvia to Greece

The IMF's Road to Ruin

April 30 - May 2, 2010

By MARK WEISBROT

Latvia has experienced the worst two-year economic downturn on recorde, losing more than 25 percent of GDP. It is projected to shrink further during the first half of this year, before beginning a slow recovery, in which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that it will not reach even its 2006 level of output by 2015 – nine years later.

With 22 percent unemployment, a sharp increase in emigration and cuts to education funding that will cause long-term damage, the social costs of this trajectory are also high.

By keeping its currency pegged to the euro, the government gives up the opportunity to allow a depreciation that would stimulate growth by improving the trade balance. But even more importantly, maintaining the peg means that Latvia cannot use expansionary monetary policy, or expansionary fiscal policy, to get out of recession. (The United States has used both: in addition to its fiscal stimulus and cutting interest rates to near zero, it has created more than 1.5 trillion dollars since the recession began).

Some who believe that doing the opposite of what rich countries do – i.e. pro-cyclical policies -- can work point to neighboring Estonia as a success story. Estonia has kept its currency pegged to the Euro, and like Latvia is trying to accomplish an “internal devaluation.” In other words, with a deep enough recession and sufficient unemployment, wages and prices can be pushed down. In theory this would allow the economy to become competitive again, even while keeping the (nominal) exchange rate fixed.

But the cost to Estonia has been almost as high as in Latvia. The economy has shrunk by nearly 20 percent. Unemployment has shot up from about 2 percent to 15.5 percent. And recovery is expected to be painfully slow: the IMF projects that the economy will grow by just 0.8 percent this year. Amazingly, by 2015 Estonia is projected to still be less welloff than it was in 2007. This is an enormous cost in terms of lost actual and potential output, as well as the social costs associated with high long-term unemployment that will accompany this slow recovery. And despite the economic collapse and a sharp drop in wages, Estonia’s real effective exchange rate was the same at the end of last year as it was at the beginning of 2008 – in other words, no “internal devaluation” had occurred.

Yet Estonia is being held up as a positive example, even used to attack economists who have criticized pro-cyclical policies in Latvia. The reason is that Estonia has not had the swelling deficit and debt problems that Latvia has had in the downturn. Its public debt of 7 percent of GDP is a small fraction of the EU average of 79 percent, and its budget deficit for 2009 was just 1.7 percent of GDP. It is therefore on its way to join the Euro zone, perhaps adopting the Euro at the beginning of next year.

How did Estonia manage to avoid a large increase in its debt during this severe downturn? First, the government had accumulated assets during the expansion, amounting to some 12 percent of GDP; and it was also running a budget surplus when the recession hit. And it has received quite a bit in grants from the European Union: In 2010, the IMF projects an enormous 8.3 percent of GDP in grants, with 6.7 percent of GDP the prior year.

Greece, unfortunately, is not being offered any grants from the European Union or the IMF. Their plan for Greece is all about pain and punishment. And with a public debt of 115 percent of GDP and a budget deficit of 13.6 percent, Greece will be forced to make spending cuts that will not only have drastic social consequences but will almost certainly plunge the country deeper into recession.

This is a train going in the wrong direction, and once you go down this track there is no telling where the end will be. Greece – like Latvia and Estonia – will be at the mercy of external events to rescue its economy. A rapid, robust rebound in the European Union – which nobody is projecting – could lift these countries out of their slump with a huge boost in demand for their exports, and capital inflows as in the bubble years. Or not: Western European banks still have hundreds of billions of bad loans to Central and Eastern Europe from the bubble years. Some big shoes could still drop that would depress regional growth even below the slow recovery that is projected for the Euro zone. Germany, which has been dependent on exports for all of its growth from 2002-2007, could continue to soak up the regional trade benefits of a Euro zone and/or world recovery.

Now matter how you slice it, these 19th-century-brutal pro-cyclical policies don’t make sense. They are also grossly unfair, placing the burden of adjustment most squarely on poor and working people. I would not wish Estonia’s “success” on any population, simply because they avoided a debt run-up and are on track to join the Euro. They may find, like Greece – as well as Spain, Ireland, Portugal and Italy – that the costs of adopting a currency that is overvalued for a country’s level of productivity are potentially quite high over the long run, even after these economies eventually recover.

The European Union and the IMF have the money and the ability to engineer a recovery based on counter-cyclical policies in Greece as well as the Baltic states. If it involves a debt restructuring – or even a haircut for the bondholders - so be it. No government should accept policies that tell them they must bleed their economy for an indeterminate time before it can recover.

Mark Weisbrot is an economist and co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. He is co-author, with Dean Baker, of Social Security: the Phony Crisis.

This article was originally published in The Guardian.

"Why Greece Will Default"

Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou announces Greece's decision to request activation of a joint eurozone-International Monetary Fund financial rescue plan, from the Greek Aegean island of Kastellorizo, April 23, 2010.

AP Photo

Op-Ed, Project Syndicate

April 28, 2010

Author: Martin Feldstein, George F. Baker Professor of Economics at Harvard University

CAMBRIDGE - Greece will default on its national debt. That default will be due in large part to its membership in the European Monetary Union. If it were not part of the euro system, Greece might not have gotten into its current predicament and, even if it had gotten into its current predicament, it could have avoided the need to default.

Greece's default on its national debt need not mean an explicit refusal to make principal and interest payments when they come due. More likely would be an IMF-organized restructuring of the existing debt, swapping new bonds with lower principal and interest for existing bonds. Or it could be a "soft default" in which Greece unilaterally services its existing debt with new debt rather than paying in cash. But, whatever form the default takes, the current owners of Greek debt will get less than the full amount that they are now owed.

The only way that Greece could avoid a default would be by cutting its future annual budget deficits to a level that foreign and domestic investors would be willing to finance on a voluntary basis. At a minimum, that would mean reducing the deficit to a level that stops the rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

To achieve that, the current deficit of 14% of GDP would have to fall to 5% of GDP or less. But to bring the debt-to-GDP ratio to the 60% level prescribed by the Maastricht Treaty would require reducing the annual budget deficit to just 3% of GDP - the goal that the eurozone's finance ministers have said that Greece must achieve by 2012.

Reducing the budget deficit by 10% of GDP would mean an enormous cut in government spending or a dramatic rise in tax revenue - or, more likely, both. Quite apart from the political difficulty of achieving this would be the very serious adverse effect on aggregate domestic demand, and therefore on production and employment. Greece's unemployment rate already is 10%, and its GDP is already expected to fall at an annual rate of more than 4%, pushing joblessness even higher.

Depressing economic activity further through higher taxes and reduced government spending would cause offsetting reductions in tax revenue and offsetting increases in transfer payments to the unemployed. So everyplanned euro of deficit reduction delivers less than a euro of actual deficit reduction. That means that planned tax increases and cuts in basic government spending would have to be even larger than 10% of GDP in order to achieve a 3%-of-GDP budget deficit.

There simply is no way around the arithmetic implied by the scale of deficit reduction and the accompanying economic decline: Greece's default on its debt is inevitable.

Greece might have been able to avoid that outcome if it were not in the eurozone. If Greece still had its own currency, the authorities could devalue it while tightening fiscal policy. A devalued currency would increase exports and would cause Greek households and firms to substitute domestic products for imported goods. The increased demand for Greek goods and services would raise Greece's GDP, increasing tax revenue and reducing transfer payments. In short, fiscal consolidation would be both easier and less painful if Greece had its own monetary policy.

Greece's membership in the eurozone was also a principal cause of its current large budget deficit. Because Greece has not had its own currency for more than a decade, there has been no market signal to warn Greece that its debt was growing unacceptably large.

If Greece had remained outside the eurozone and retained the drachma, the large increased supply of Greek bonds would cause the drachma to decline and the interest rate on the bonds to rise. But, because Greek euro bonds were regarded as a close substitute for other countries' euro bonds, the interest rate on Greek bonds did not rise as Greece increased its borrowing - until the market began to fear a possible default.

The substantial surge in the interest rate on Greek bonds relative to German bonds in the past few weeks shows that the market now regards such a default as increasingly likely. The combination of credits from the other eurozone countries and lending by the IMF may provide enough liquidity to stave off default for a while. In exchange for this liquidity support, Greece will be forced to accept painful fiscal tightening and falling GDP.

In the end, Greece, the eurozone's other members, and Greece's creditors will have to accept that the country is insolvent and cannot service its existing debt. At that point, Greece will default.

For more information about this publication please contact the Belfer Center Communications Office at 617-495-9858.

For Academic Citation:

Feldstein, Martin. "Why Greece Will Default." Project Syndicate, April 28, 2010.

When is a Fraud Not a Fraud? (Greece-Goldman Edition)

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

The short answer to the question in the headline is “When there are no rules.”

A headline in a current Bloomberg story illustrates the problem: “Goldman Sachs, Greece Didn’t Disclose Swap, Investors ‘Fooled’.”

“Fooled” is an unusual choice of words, particularly when applied to to presumed grown-ups like institutional investors and international overseers. Bloomberg seems to be mincing around the more obvious F-words, like “fraud” (as in defrauded) or “fleeced.”

Although there is a considerable amount of well-warranted consternation about how Goldman sold swaps to Greece that allowed it to mask how bad its deteriorating finances were from the EU budget police, there has been perilous little discussion of why the fact that this was permissible says there is something very wrong with the rules in place.

The latest twist is that Goldman managed $15 billion of debt sales for Greece after the debt-disguising swaps were in place, and (needless to say) there was no disclosure of the existence of the hidden debt (Bloomberg was able to obtain only six of ten prospectuses in question and found no mention of the swaps; it seems pretty unlikely that the others disclosed their existence). That means investors were hoodwinked. It goes without saying they would have seen Greece as a worse credit risk if they had been in full possession of the facts, and would presumably have required a higher interest rate.

Yet we get amazingly weak statements from the experts quizzed by Bloomberg:

Goldman could face legal liability “if it could be established that they were knowingly hiding risk, and therefore knew or had reason to know that the bond disclosure documents were misleading,” said Thomas Hazen, a law professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “But that would be a tough hill to climb, in terms of burden of proof. There’d have to be some sort of smoking-gun memo.”

Yves here. I’m not certain how much a US law professor knows about the securities laws that govern this particular offering (as in it most certainly is NOT US securities regs). But there seem to be three issues:

1. What disclosure standards would apply to the Greece bond offering. The offering memorandum, from a legal standpoint, is the issuer’s document, meaning Greece’s, not Goldman’s. So any shortcoming in disclosure is a liability issue for Greece (no joke, the deal manager makes the issuer sign a little letter acknowledging what portions of the offering memo were provided by it, and it is just a few sentences, like the selling price of the bonds, the underwriters’ spread, stuff like that. The description of the issuer and the securities themselves is most assuredly NOT the responsibility of the underwriters. Update: this is a simplification, and arguably an oversimplification; reader Brown Ram in comments describes how underwriters absolve themselves almost entirely from liability for the accuracy of offering documents).

2. OK, but what about this famous due diligence that investment bankers are supposed to perform? Well I have to tell you, even in good old SEC land, it’s less than you might think. In my day, the only thing that seemed to be required was visiting the major facilities of a new issuer (as in a company doing an IPO or first bond offering) and having outside counsel read board minutes (and tell the managers if they saw anything they found troubling).

3. But in this case, we have an interesting conundrum. Goldman clearly HAD TO KNOW the Greek offering documents were incomplete, right? They had arranged those swaps, they knew there was more debt than Greece was ‘fessing up to in its later offering memoranda.

Point 3 is where matters get a bit sticky. Under SEC regs, the failure to mention the swaps or their effect (that there was additional debt that had been deferred) would be a violation. This is a simplification, , but the concept is that the offering documents have to make a full and fair disclosure. That means not only do the statement made need to be accurate as of the date when they were made, but further more, they cannot fail to state a material fact if leaving that information out would be misleading. So question is whether under the regs governing this deal, whether an omission of this sort would also be considered a regulatory violation and/or an investor fraud.

If so, it’s pretty clear Greece defrauded investors. But what about Goldman? Here, Prof. Hazen is far too charitable to Goldman. “Smoking gun memo?” No, you just need to understand how Goldman works. Even though my knowledge is dated, I strongly suspect the firm is still organized more or less the same way, because it was considered a competitive strength and was widely emulated in the industry (t had the effect of creating loyalty to the brand rather than individuals).

Goldman has centralized account management. One person, a relationship manager, is ultimately responsible for selling all products to particular corporate clients and government entities. His full time job is client coverage; he then works with product specialists as needed to get deals done (specialists are also assigned to particular accounts, but the relationship manager is always in the mix. Hank Paulson was one of these relationship managers, called investment banking services). So Goldman cannot pretend that somehow the team that handled the bond offering didn’t know about the swaps deal. That’s unlikely to begin with, given Goldman’s fetish about communication, but structurally impossible (the new business guy would have known about both sets of deals).

In addition, Goldman new business officers (the account managers) are required to document every meeting with the client (this is to protect the firm in case someone is hit by a bus or leaves the firm). This was also a long-standing fetish. In the 1980s, I as a junior account member could ask the library for the “credit memos” as these notes were called. On well-established clients, the meeting notes went back to the 1950s.

So I’m not certain you need a particular memo, even though such documents probably exist. All you need to do is walk through the structure of Goldman relationship management and their usual client communication protocols to establish that it is just not credible that the team working on the bond issues could not have known about the swaps. Then you just need to figure out a legal theory as to why what Goldman did was not kosher (presumably it was an investor fraud, but you’d need the relevant statutes and precedents).