U.S. healthcare is in crisis.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZAMtgCtq1oU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nG6ppzJwPYU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6JMf-U75fTg

Moderators: Elvis, DrVolin, Jeff

100 Million People in America Are Saddled With Health Care Debt

“Debt is no longer just a bug in our system. It is one of the main products,” said Dr. Rishi Manchanda, who has worked with low-income patients in California for more than a decade and served on the board of the nonprofit RIP Medical Debt. “We have a health care system almost perfectly designed to create debt.”

The burden is forcing families to cut spending on food and other essentials. Millions are being driven from their homes or into bankruptcy, the poll found.

...

Medical debt is piling additional hardships on people with cancer and other chronic illnesses. Debt levels in U.S. counties with the highest rates of disease can be three or four times what they are in the healthiest counties, according to an Urban Institute analysis.

The debt is also deepening racial disparities.

And it is preventing Americans from saving for retirement, investing in their children’s educations, or laying the traditional building blocks for a secure future, such as borrowing for college or buying a home. Debt from health care is nearly twice as common for adults under 30 as for those 65 and older, the KFF poll found.

Perhaps most perversely, medical debt is blocking patients from care.

...

About 1 in 7 people with debt said they’ve been denied access to a hospital, doctor, or other provider because of unpaid bills, according to the poll. An even greater share ― about two-thirds ― have put off care they or a family member need because of cost.

“It’s barbaric,” said Dr. Miriam Atkins, a Georgia oncologist...

Hospitals recorded their most profitable year on record in 2019, notching an aggregate profit margin of 7.6%, according to the federal Medicare Payment Advisory Committee. Many hospitals thrived even through the pandemic.

...

Patient debt is also sustaining a shadowy collections business fed by hospitals ― including public university systems and nonprofits granted tax breaks to serve their communities ― that sell debt in private deals to collections companies that, in turn, pursue patients.

“People are getting harassed at all hours of the day. Many come to us with no idea where the debt came from,” said Eric Zell, a supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland. “It seems to be an epidemic.”

...

As of last year, 58% of debts recorded in collections were for a medical bill, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. That’s nearly four times as many debts attributable to telecom bills, the next most common form of debt on credit records.

But the medical debt on credit reports represents only a fraction of the money that Americans owe for health care, the KHN-NPR investigation shows.

...

Sherrie Foy, 63, and her husband, Michael, saw their carefully planned retirement upended when Foy’s colon had to be removed.

After Michael retired from Consolidated Edison in New York, the couple moved to rural southwestern Virginia. Sherrie had the space to care for rescued horses.

The couple had diligently saved. And they had retiree health insurance through Con Edison. But Sherrie’s surgery led to numerous complications, months in the hospital, and medical bills that passed the $1 million cap on the couple’s health plan.

When Foy couldn’t pay more than $775,000 she owed the University of Virginia Health System, the medical center sued, a once common practice that the university said it has reined in. The couple declared bankruptcy.

The Foys cashed in a life insurance policy to pay a bankruptcy lawyer and liquidated savings accounts the couple had set up for their grandchildren.

“They took everything we had,” Foy said. “Now we have nothing.”

https://khn.org/news/article/diagnosis- ... ical-debt/

Private equity firms now control many hospitals, ERs and nursing homes. Is it good for health care?

Private equity firms are buying up hospitals, nursing homes and ER operations. The drive for profits can run counter to helping patients, critics say.

ay 13, 2020, 2:55 AM PDT

By Gretchen Morgenson and Emmanuelle Saliba

In March, as the coronavirus gripped the nation, veteran emergency room doctor Ming Lin was growing concerned. Lin felt his facility, PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Washington, was unprepared for the pandemic, so he went to his superiors for help.

Frustrated by their response, Lin took to social media, criticizing the hospital's operations in a series of posts.

Days later, the hospital removed Lin from the rotation in the emergency department. He had worked at PeaceHealth for 17 years.

Under typical medical industry practice, Lin's case would have been subject to peer review, experts said. But Lin's employer wasn't PeaceHealth. It was TeamHealth, a physician practice and staffing company that provides the hospital with emergency room services. TeamHealth is owned by Blackstone Group, a finance giant.

When a private staffing firm teams up with a hospital, the right to due process can disappear. Lin's case was never heard.

"One of the objectives is to point out any deficiencies in the system that may harm the patient," Lin told NBC News. "Because private equity has taken over health care, it has made that difficult."

Blackstone, which bought TeamHealth in 2016 for $6.1 billion, is what's known as a private equity firm, a type of financial entity that buys companies and hopes to sell them later at a profit.

Over the past decade, private equity firms like Blackstone, Apollo Global Management, The Carlyle Group, KKR & Co. and Warburg Pincus have deployed more than $340 billion to buy health care-related operations around the world. In 2019, private equity's health care acquisitions reached $79 billion, a record, according to Bain & Co., a consulting firm.

Private equity's purchases have included rural hospitals, physicians' practices, nursing homes and hospice centers, air ambulance companies and health care billing management and debt collection systems.

Partly as a result of private equity purchases, many formerly doctor-owned practices no longer are. The American Medical Association recently reported that 2018 was the first year in which more physicians were employees — 47.4 percent — than owners of their practices — 45.9 percent. In 1988, 72.1 percent of medical practices were owned by physicians.

In some parts of the health care industry, private equity firms dominate. For example, TeamHealth, owned by Blackstone, and Envision Healthcare, owned by KKR, provide staffing for about a third of the country's emergency rooms.

This has been a seismic shift. During the 1900s, most hospitals were owned either by nonprofit entities with religious affiliations or by states and cities, with ties to medical schools. For-profit hospitals existed, but it wasn't until recently that they became nearly ubiquitous.

For the past 20 years, private equity has been a source of immense wealth for the executives overseeing the entities. Most of those who head major private equity firms are reported to be billionaires, like the two men atop Blackstone: Stephen Schwarzman, a close adviser to President Donald Trump, and Hamilton "Tony" James, a major donor to Democrats.

The impact private equity has had on employees and customers of the companies it has taken over, however, isn't always beneficial. To finance the purchases, private equity owners typically load the companies they buy with debt. Then they slash the companies' costs to increase earnings and appeal to potential buyers down the road.

In the business of health care, the drive for profits can run counter to the goal of helping patients and protecting workers, critics say.

Research shows, for example, that when private equity firms acquire nursing homes, the quality of care declines markedly. And when COVID-19 hit, hospitals associated with private equity firms were early to cut practitioners' pay and benefits because the operations could no longer generate profits on elective surgical procedures postponed during the pandemic. The heavy debt loads typically associated with private equity-owned businesses hinder their ability to withstand profit downturns.

Finally, some medical professionals say, private equity's growing involvement in health care in recent years has contributed to shortages of ventilators, masks and other equipment needed to combat COVID-19, because keeping such goods on hand costs money. And to private equity, that's like putting dollar bills on a shelf.

Private equity firms have jumped into health care with both feet. Apollo Global Management, a $330 billion investment firm overseen by Leon Black, owns RCCH Healthcare Partners, an operator of 88 rural hospital campuses in West Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky and 26 other states. Cerberus Capital Management, a $42 billion investment firm run by Steve Feinberg, owns Steward Health Care; it runs 35 hospitals and a swath of urgent care facilities in 11 states.

Warburg Pincus, overseen by former Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, owns Modernizing Medicine, an information technology company that helps health care providers ramp up profits through medical billing and, to a lesser degree, debt collections. The Carlyle Group owns MedRisk, a leading provider of physical therapy cost-containment systems for U.S. workers' compensation payers, such as insurers and large employers.

Private equity's laser focus on cost cutting and operational efficiencies can benefit consumers, economists say, if lower costs are passed on to end users. Problems arise, however, when the push for profits reduces quality. That can be especially harmful in health care, in which patients' lives are on the line and it is difficult for consumers to comparison shop by analyzing quality of care.

Mark Reiter is residency program director of emergency medicine for the University of Tennessee and past president of American Academy of Emergency Medicine, an advocacy group for practitioners. "Private equity-backed health care has been a disaster for patients and for doctors," he told NBC News. "Many decisions are made for what is going to maximize profits for the private equity company, rather than what is best for the patient, what is best for the community."

Representatives of every firm identified in this article declined to respond to broad criticisms of private equity in the health care arena.

As for PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, spokeswoman Bev Mayhew said it removed Ming Lin from the emergency department rotation because "his actions were disruptive, compromised collaboration in the midst of a crisis and contributed to the creation of fear and anxiety among staff and the community." She said his case wasn't subject to peer review because he still has privileges at the hospital.

A TeamHealth spokesman said it continues to employ Lin and had offered to place him "in another contracted hospital anywhere in the country."

'Physician Extenders'

Private equity firms have targeted health care investments for an array of reasons, most having to do with their potential profits.

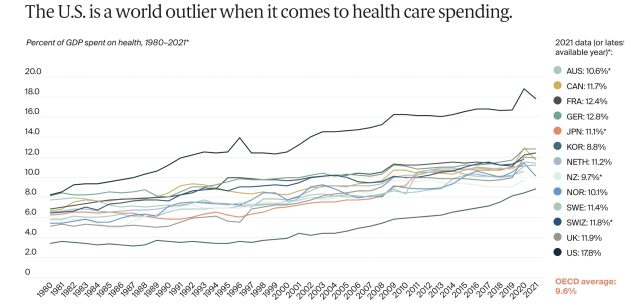

First, health care drives a huge part of the nation's economic output — almost 20 percent of gross domestic product. In addition, health care is a fragmented business with many small operators like physicians; private investors often find outsize gains in industries in which they can create economies of scale through consolidation.

Ever on the hunt for efficiencies, private equity has brought changes to traditional health care practices, experts say. One example: the use of so-called physician extenders, like nurse practitioners, to see patients instead of actual doctors.

Because such extenders have less training under their belts, their costs are well below those associated with physicians. In general, employing three extenders equals the cost of one physician, said Robert McNamara, professor and chairman of emergency medicine at Temple University and chief medical officer of Temple Faculty Physicians.

Private equity-owned firms also use practitioners with less experience or training to save money, say doctors associated with the American College of Emergency Physicians and the American Academy of Emergency Medicine.

In February, a patient arrived at the Calais Regional Hospital emergency department in Calais, Maine, near the Canadian border. He required intubation — the insertion of a breathing tube down his throat — but the doctor was unable to perform the procedure and had to call in local paramedics for help. The patient recovered.

The doctor worked for Envision Physician Services, the KKR-owned company that had taken over staffing of the emergency department two weeks before the incident.

DeeDee Travis, the hospital's spokeswoman, said that the doctor is no longer in rotation at the hospital but that his move had nothing to do with the incident. She said rural medicine requires the use of all resources, including local paramedic staff.

Assessing the impact of private equity on the overall quality of care has been difficult, in part because ownership by the firms is relatively new. But in February, four academics at the University of Pennsylvania, New York University and the University of Chicago published an in-depth study analyzing care at private equity-owned nursing homes. The findings were stark.

"In the nursing home setting," the study said, "it appears that high-powered profit maximizing incentives can lead firms to renege on implicit contracts to provide high quality care, creating value for the firms at the expense of patients."

Looking at data from 2000 to 2017 from over 18,000 nursing homes, the academics found "robust evidence of declines in patient health and compliance with care standards" after private equity concerns bought facilities. And when private equity firms' purchases of nursing homes were compared with those bought by other for-profit entities, such as nursing home chains, the private equity-owned properties resulted in greater quality declines, the study concluded.

On April 2, well into the COVID-19 crisis, Steward Health Care, owned by Cerberus Capital, created a firestorm. It suspended intensive care unit admissions at Nashoba Valley Medical Center, a hospital in rural northeastern Massachusetts, and redeployed equipment and staff elsewhere to meet COVID-19 demand, according to a memo from the president of the facility. Hospitals aren't supposed to close such units without first notifying state authorities and holding community hearings.

Audra Sprague, a longtime registered nurse at the facility, said the move "completely took out an entire level of service. Anybody that needed ICU care, we didn't have one, we couldn't keep you."

Darren Grubb, a spokesman for Steward, said that the suspension has "not impacted patient care" at the facility and that state officials had "validated that the ICU at Nashoba Valley remains adequately staffed and equipped to care for clinically appropriate patients."

Sprague said she is proud to serve patients in the same hospital where her grandmother was a nurse. She said that the facility had previously been owned by a private company but that patient safety and staff treatment had worsened since Steward took over. So she joined the nurses' union.

"Even when you say something is unsafe, there's little change that comes out of it," she said. "They're not going to do a single thing that doesn't benefit them first and foremost."

Grubb called Sprague's view a "baseless, selective, hyper-generalized claim."

For more than a century, company ownership of doctors' practices was barred under the Corporate Practice of Medicine doctrine, which was enshrined in most state laws. The doctrine and the laws hold that only individual physicians should be licensed to practice medicine, not corporations. But in the years leading up to COVID-19, the laws were rarely enforced.

"The states realized a long time ago that this is a real problem — fiduciary duty to shareholders rather than patients," Reiter said. "These corporations are not taking an oath to do what's best for their patients, and they thought it would be better if doctors owned their own practices."

In response to the laws, private equity firms have structured their health care investments with physicians as owners, but in name only, McNamara said. Staffing companies like TeamHealth, for example, use what he called sham professional associations with doctors to get around prohibitions against the corporate practice of medicine.

McHenry Lee, TeamHealth's spokesman, said the company's "organizational structure is fully compliant with long established laws and precedents." Referring to the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, Lee said the company has prevailed while facing judicial scrutiny "initiated or funded by AAEM, where Dr. McNamara has made identical charges."

In a typical emergency room, McNamara said, the usual physician group charges three to four times the Medicare rate. TeamHealth is charging six times, he said.

Last fall, United Healthcare, the giant insurer, canceled coverage at 500 hospitals with TeamHealth-run emergency rooms, largely because of high costs, a company spokeswoman said.

"A small number of providers are driving up the cost of care for the people and customers we serve," she said. "This is particularly evident with private equity-backed physician staffing companies like TeamHealth."

United Healthcare provided NBC News with examples of TeamHealth costs far exceeding median charges for specific emergency department procedures. A patient visiting an emergency department with chest pains, for example, would face a median charge of $340, United Healthcare said, versus a TeamHealth bill for $976. Stitches on a minor cut would be $200 at the median rate, compared with $888 from TeamHealth. And the median rate for a broken arm is $665, while TeamHealth's charge is $2,947.

Lee of TeamHealth declined to comment on the figures.

Envision Healthcare is a physician staffing, emergency medicine and billing services company bought for almost $10 billion by KKR in 2018. Envision's website says it provides emergency medicine at 650 facilities in 40 states.

Before the acquisition, Envision acknowledged in a 2014 securities filing that its contracts with physician groups might run afoul of laws barring the corporate practice of medicine, as well as fee-sharing arrangements between doctors and companies. It could be subject to civil or criminal penalties, and its contracts with affiliated physician groups "could be found legally invalid and unenforceable," Envision said in the filing.

A flurry of such cases didn't arise. But today, Envision's business has collapsed, again a result of postponed elective operations. Carrying $7.5 billion in debt, the company recently hired restructuring advisers and may file for bankruptcy.

Aliese Polk, a spokeswoman for Envision, said the company is experiencing the same financial problems that many other health care providers are and is "focused on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, deploying significant resources to front-line clinicians caring for sick patients." She declined to discuss its previous warnings about possible legal violations in its business model.

Congress and private equity health care

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, private equity-owned health care operations had come under criticism from members of Congress and outsiders.

TeamHealth, for example, was featured last year in a report by MLK50 and ProPublica for aggressively suing poor patients who had been unable to pay their emergency room bills. After the report, TeamHealth said it would stop the practice. The TeamHealth spokesman didn't respond to a question from NBC News about why it sued patients.

Surprise emergency care medical bills have also emerged as a problem at private equity-run Envision. Patients can be ambushed by such bills when they visit an emergency department in a hospital that is in their insurance network but whose doctors work outside the network, charging separately for their services.

Polk of Envision declined to comment on the company's role in surprise billing.

Congress tried to address the problematic practice with legislation last year. But as the bill gained traction, Envision and TeamHealth quietly backed a purported grass roots organization called Doctor Patient Unity to advocate against the legislation, according to The New York Times. Doctor Patient Unity funded a $28 million media blitz against the bill, the report said, which didn't pass.

Doctor Patient Unity didn't respond to an email seeking comment. Representatives from TeamHealth and Envision accused insurance companies of causing problems for patients seeking emergency care and said they didn't support the legislation because it would have benefited insurers at the expense of patients.

Emily Maddoff and Chet Waldman, lawyers at Wolf Popper LLP, are fighting surprise medical bills in six class-action lawsuits in state and federal courts across the country. A unit of Envision is a defendant in three of the cases.

A class-action case involving a patient in California has a final settlement hearing scheduled for June. If approved, the deal would provide 100 percent relief to the plaintiffs.

"We should not be running our health care system as a profit-making operation on steroids," said Eileen Appelbaum, an authority on private equity and co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a left-leaning think tank in Washington, D.C. "Health care is not so much anymore about taking care of patients. It's way more about making money."

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-c ... s-n1203161

https://khn.org/news/article/diagnosis- ... ical-debt/

100 Million People in America Are Saddled With Health Care Debt

By Noam N. Levey

June 16, 2022

Elizabeth Woodruff drained her retirement account and took on three jobs after she and her husband were sued for nearly $10,000 by the New York hospital where his infected leg was amputated.

Ariane Buck, a young father in Arizona who sells health insurance, couldn’t make an appointment with his doctor for a dangerous intestinal infection because the office said he had outstanding bills.

Allyson Ward and her husband loaded up credit cards, borrowed from relatives, and delayed repaying student loans after the premature birth of their twins left them with $80,000 in debt. Ward, a nurse practitioner, took on extra nursing shifts, working days and nights.

“I wanted to be a mom,” she said. “But we had to have the money.”

The three are among more than 100 million people in America ― including 41% of adults ― beset by a health care system that is systematically pushing patients into debt on a mass scale, an investigation by KHN and NPR shows.

The investigation reveals a problem that, despite new attention from the White House and Congress, is far more pervasive than previously reported. That is because much of the debt that patients accrue is hidden as credit card balances, loans from family, or payment plans to hospitals and other medical providers.

To calculate the true extent and burden of this debt, the KHN-NPR investigation draws on a nationwide poll conducted by KFF for this project. The poll was designed to capture not just bills patients couldn’t afford, but other borrowing used to pay for health care as well. New analyses of credit bureau, hospital billing, and credit card data by the Urban Institute and other research partners also inform the project. And KHN and NPR reporters conducted hundreds of interviews with patients, physicians, health industry leaders, consumer advocates, and researchers.

The picture is bleak.

In the past five years, more than half of U.S. adults report they’ve gone into debt because of medical or dental bills, the KFF poll found.

A quarter of adults with health care debt owe more than $5,000. And about 1 in 5 with any amount of debt said they don’t expect to ever pay it off.

“Debt is no longer just a bug in our system. It is one of the main products,” said Dr. Rishi Manchanda, who has worked with low-income patients in California for more than a decade and served on the board of the nonprofit RIP Medical Debt. “We have a health care system almost perfectly designed to create debt.”

The burden is forcing families to cut spending on food and other essentials. Millions are being driven from their homes or into bankruptcy, the poll found.

Medical debt is piling additional hardships on people with cancer and other chronic illnesses. Debt levels in U.S. counties with the highest rates of disease can be three or four times what they are in the healthiest counties, according to an Urban Institute analysis.

The debt is also deepening racial disparities.

And it is preventing Americans from saving for retirement, investing in their children’s educations, or laying the traditional building blocks for a secure future, such as borrowing for college or buying a home. Debt from health care is nearly twice as common for adults under 30 as for those 65 and older, the KFF poll found.

Perhaps most perversely, medical debt is blocking patients from care.

About 1 in 7 people with debt said they’ve been denied access to a hospital, doctor, or other provider because of unpaid bills, according to the poll. An even greater share ― about two-thirds ― have put off care they or a family member need because of cost.

“It’s barbaric,” said Dr. Miriam Atkins, a Georgia oncologist who, like many physicians, said she’s had patients give up treatment for fear of debt.

Patient debt is piling up despite the landmark 2010 Affordable Care Act.

The law expanded insurance coverage to tens of millions of Americans. Yet it also ushered in years of robust profits for the medical industry, which has steadily raised prices over the past decade.

Hospitals recorded their most profitable year on record in 2019, notching an aggregate profit margin of 7.6%, according to the federal Medicare Payment Advisory Committee. Many hospitals thrived even through the pandemic.

But for many Americans, the law failed to live up to its promise of more affordable care. Instead, they’ve faced thousands of dollars in bills as health insurers shifted costs onto patients through higher deductibles.

Now, a highly lucrative industry is capitalizing on patients’ inability to pay. Hospitals and other medical providers are pushing millions into credit cards and other loans. These stick patients with high interest rates while generating profits for the lenders that top 29%, according to research firm IBISWorld.

Patient debt is also sustaining a shadowy collections business fed by hospitals ― including public university systems and nonprofits granted tax breaks to serve their communities ― that sell debt in private deals to collections companies that, in turn, pursue patients.

“People are getting harassed at all hours of the day. Many come to us with no idea where the debt came from,” said Eric Zell, a supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland. “It seems to be an epidemic.”

In Debt to Hospitals, Credit Cards, and Relatives

America’s debt crisis is driven by a simple reality: Half of U.S. adults don’t have the cash to cover an unexpected $500 health care bill, according to the KFF poll.

As a result, many simply don’t pay. The flood of unpaid bills has made medical debt the most common form of debt on consumer credit records.

As of last year, 58% of debts recorded in collections were for a medical bill, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. That’s nearly four times as many debts attributable to telecom bills, the next most common form of debt on credit records.

But the medical debt on credit reports represents only a fraction of the money that Americans owe for health care, the KHN-NPR investigation shows.

- About 50 million adults ― roughly 1 in 5 ― are paying off bills for their own care or a family member’s through an installment plan with a hospital or other provider, the KFF poll found. Such debt arrangements don’t appear on credit reports unless a patient stops paying.

- One in 10 owe money to a friend or family member who covered their medical or dental bills, another form of borrowing not customarily measured.

- Still more debt ends up on credit cards, as patients charge their bills and run up balances, piling high interest rates on top of what they owe for care. About 1 in 6 adults are paying off a medical or dental bill they put on a card.

How much medical debt Americans have in total is hard to know because so much isn’t recorded. But an earlier KFF analysis of federal data estimated that collective medical debt totaled at least $195 billion in 2019, larger than the economy of Greece.

[GRAPH]

The credit card balances, which also aren’t recorded as medical debt, can be substantial, according to an analysis of credit card records by the JPMorgan Chase Institute. The financial research group found that the typical cardholder’s monthly balance jumped 34% after a major medical expense.

Monthly balances then declined as people paid down their bills. But for a year, they remained about 10% above where they had been before the medical expense. Balances for a comparable group of cardholders without a major medical expense stayed relatively flat.

It’s unclear how much of the higher balances ended up as debt, as the institute’s data doesn’t distinguish between cardholders who pay off their balance every month from those who don’t. But about half of cardholders nationwide carry a balance on their cards, which usually adds interest and fees.

Which Large Counties Have the Worst Debt Problems?

Among the 20 most populous counties in the U.S., the share of people with medical debt is highest in Texas counties (to the right) and lowest in New York and California (to the left). The size of the circles denotes the median amount of debt held by residents in each county. Hover or tap on the circles for more detail.

[GRAPH]

Debts Large and Small

For many Americans, debt from medical or dental care may be relatively low. About a third owe less than $1,000, the KFF poll found.

Even small debts can take a toll.

Edy Adams, a 31-year-old medical student in Texas, was pursued by debt collectors for years for a medical exam she received after she was sexually assaulted.

Adams had recently graduated from college and was living in Chicago.

Police never found the perpetrator. But two years after the attack, Adams started getting calls from collectors saying she owed $130.68.

Illinois law prohibits billing victims for such tests. But no matter how many times Adams explained the error, the calls kept coming, each forcing her, she said, to relive the worst day of her life.

Sometimes when the collectors called, Adams would break down in tears on the phone. “I was frantic,” she recalled. “I was being haunted by this zombie bill. I couldn’t make it stop.”

Health care debt can also be catastrophic.

Sherrie Foy, 63, and her husband, Michael, saw their carefully planned retirement upended when Foy’s colon had to be removed.

After Michael retired from Consolidated Edison in New York, the couple moved to rural southwestern Virginia. Sherrie had the space to care for rescued horses.

The couple had diligently saved. And they had retiree health insurance through Con Edison. But Sherrie’s surgery led to numerous complications, months in the hospital, and medical bills that passed the $1 million cap on the couple’s health plan.

When Foy couldn’t pay more than $775,000 she owed the University of Virginia Health System, the medical center sued, a once common practice that the university said it has reined in. The couple declared bankruptcy.

The Foys cashed in a life insurance policy to pay a bankruptcy lawyer and liquidated savings accounts the couple had set up for their grandchildren.

“They took everything we had,” Foy said. “Now we have nothing.”

About 1 in 8 medically indebted Americans owe $10,000 or more, according to the KFF poll.

Although most expect to repay their debt, 23% said it will take at least three years; 18% said they don’t expect to ever pay it off.

Medical Debt’s Wide Reach

Debt has long lurked in the shadows of American health care.

In the 19th century, male patients at New York’s Bellevue Hospital had to ferry passengers on the East River and new mothers had to scrub floors to pay their debts, according to a history of American hospitals by Charles Rosenberg.

The arrangements were mostly informal, however. More often, physicians simply wrote off bills patients couldn’t afford, historian Jonathan Engel said. “There was no notion of being in medical arrears.”

Today, debt from medical and dental bills touches nearly every corner of American society, burdening even those with insurance coverage through work or government programs such as Medicare.

Who Has Health Care Debt?

Share of adults who have had health care debt in the past five years:

[GRAPH]

Nearly half of Americans in households making more than $90,000 a year have incurred health care debt in the past five years, the KFF poll found.

Women are more likely than men to be in debt. And parents more commonly have health care debt than people without children.

But the crisis has landed hardest on the poorest and uninsured.

Debt is most widespread in the South, an analysis of credit records by the Urban Institute shows. Insurance protections there are weaker, many of the states haven’t expanded Medicaid, and chronic illness is more widespread.

Where Medical Debt Hits the Hardest in the US

The share of people with medical or dental bills in collections varies widely from one county to another

[GRAPH]

Nationwide, according to the poll, Black adults are 50% more likely and Hispanic adults 35% more likely than whites to owe money for care. (Hispanics can be of any race or combination of races.)

In some places, such as the nation’s capital, disparities are even larger, Urban Institute data shows: Medical debt in Washington, D.C.’s predominantly minority neighborhoods is nearly four times as common as in white neighborhoods.

In minority communities already struggling with fewer educational and economic opportunities, the debt can be crippling, said Joseph Leitmann-Santa Cruz, chief executive of Capital Area Asset Builders, a nonprofit that provides financial counseling to low-income Washington residents. “It’s like having another arm tied behind their backs,” he said.

Medical debt can also keep young people from building savings, finishing their education, or getting a job. One analysis of credit data found that debt from health care peaks for typical Americans in their late 20s and early 30s, then declines as they get older.

Cheyenne Dantona’s medical debt derailed her career before it began.

Dantona, 31, was diagnosed with blood cancer while in college. The cancer went into remission, but when Dantona changed health plans, she was hit with thousands of dollars of medical bills because one of her primary providers was out of network.

She enrolled in a medical credit card, only to get stuck paying even more in interest. Other bills went to collections, dragging down her credit score. Dantona still dreams of working with injured and orphaned wild animals, but she’s been forced to move back in with her mother outside Minneapolis.

“She’s been trapped,” said Dantona’s sister, Desiree. “Her life is on pause.”

What Kind of Health Care Debt Do Americans Have?

Share of adults who have the following types of health care debt:

Bills past due or bills they can't pay 24%

Payment plan with a medical provider 21%

Owe a bank, collection agency, or other lender 17%

Credit card they are paying off over time 17%

Owe family member or friend 10%

Total who have some kind of health care debt 41%

Barriers to Care

Desiree Dantona said the debt has also made her sister hesitant to seek care to ensure her cancer remains in remission.

Medical providers say this is one of the most pernicious effects of America’s debt crisis, keeping the sick away from care and piling toxic stress on patients when they are most vulnerable.

The financial strain can slow patients’ recovery and even increase their chances of death, cancer researchers have found.

Yet the link between sickness and debt is a defining feature of American health care, according to the Urban Institute, which analyzed credit records and other demographic data on poverty, race, and health status.

U.S. counties with the highest share of residents with multiple chronic conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease, also tend to have the most medical debt. That makes illness a stronger predictor of medical debt than either poverty or insurance.

In the 100 U.S. counties with the highest levels of chronic disease, nearly a quarter of adults have medical debt on their credit records, compared with fewer than 1 in 10 in the healthiest counties.

More Disease, More Debt

Counties with a large share of people with multiple chronic conditions (in red) tend to have higher levels of debt than counties with less illness (beige). Each dot represents a county.

[GRAPH]

The problem is so pervasive that even many physicians and business leaders concede debt has become a black mark on American health care.

“There is no reason in this country that people should have medical debt that destroys them,” said George Halvorson, former chief executive of Kaiser Permanente, the nation’s largest integrated medical system and health plan. KP has a relatively generous financial assistance policy but does sometimes sue patients. (The health system is not affiliated with KHN.)

Halvorson cited the growth of high-deductible health insurance as a key driver of the debt crisis. “People are getting bankrupted when they get care,” he said, “even if they have insurance.”

Washington’s Role

The Affordable Care Act bolstered financial protections for millions of Americans, not only increasing health coverage but also setting insurance standards that were supposed to limit how much patients must pay out of their own pockets.

By some measures, the law worked, research shows. In California, there was an 11% decline in the monthly use of payday loans after the state expanded coverage through the law.

But the law’s caps on out-of-pocket costs have proven too high for most Americans. Federal regulations allow out-of-pocket maximums on individual plans up to $8,700.

Debt Hits Even High-Income and Insured People

Share of adults who have had health care debt in the past five years:

[GRAPH]

Additionally, the law did not stop the growth of high-deductible plans, which have become standard over the past decade. That has forced many Americans to pay thousands of dollars out of their own pockets before their coverage kicks in.

Last year the average annual deductible for a single worker with job-based coverage topped $1,400, almost four times what it was in 2006, according to an annual employer survey by KFF. Family deductibles can top $10,000.

While health plans are requiring patients to pay more, hospitals, drugmakers, and other medical providers are raising prices.

From 2012 to 2016, prices for medical care surged 16%, almost four times the rate of overall inflation, a report by the nonprofit Health Care Cost Institute found.

For many Americans, the combination of high prices and high out-of-pocket costs almost inevitably means debt. The KFF poll found that 6 in 10 working-age adults with coverage have gone into debt getting care in the past five years, a rate only slightly lower than the uninsured.

Even Medicare coverage can leave patients on the hook for thousands of dollars in charges for drugs and treatment, studies show.

About a third of seniors have owed money for care, the poll found. And 37% of these said they or someone in their household have been forced to cut spending on food, clothing, or other essentials because of what they owe; 12% said they’ve taken on extra work.

The widespread burden of medical debt has sparked new interest from elected officials, regulators, and industry leaders.

In March, following warnings from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the major credit reporting companies said they would remove medical debts under $500 and those that had been repaid from consumer credit reports.

In April, the Biden administration announced a new CFPB crackdown on debt collectors and an initiative by the Department of Health and Human Services to gather more information on how hospitals provide financial aid.

The actions were applauded by patient advocates. However, the changes likely won’t address the root causes of this national crisis.

“The No. 1 reason, and the No. 2, 3, and 4 reasons, that people go into medical debt is they don’t have the money,” said Alan Cohen, a co-founder of insurer Centivo who has worked in health benefits for more than 30 years. “It’s not complicated.”

Buck, the father in Arizona who was denied care, has seen this firsthand while selling Medicare plans to seniors. “I’ve had old people crying on the phone with me,” he said. “It’s horrifying.”

Now 30, Buck faces his own struggles. He recovered from the intestinal infection, but after being forced to go to a hospital emergency room, he was hit with thousands of dollars in medical bills.

More piled on when Buck’s wife landed in an emergency room for ovarian cysts.

Today the Bucks, who have three children, estimate they owe more than $50,000, including medical bills they put on credit cards that they can’t pay off.

“We’ve all had to cut back on everything,” Buck said. The kids wear hand-me-downs. They scrimp on school supplies and rely on family for Christmas gifts. A dinner out for chili is an extravagance.

“It pains me when my kids ask to go somewhere, and I can’t,” Buck said. “I feel as if I’ve failed as a parent.”

The couple is preparing to file for bankruptcy.About This Project

“Diagnosis: Debt” is a reporting partnership between KHN and NPR exploring the scale, impact, and causes of medical debt in America.

The series draws on the “KFF Health Care Debt Survey,” a poll designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at KFF in collaboration with KHN journalists and editors. The survey was conducted Feb. 25 through March 20, 2022, online and via telephone, in English and Spanish, among a nationally representative sample of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,292 adults with current health care debt and 382 adults who had health care debt in the past five years. The margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3 percentage points for the full sample and 3 percentage points for those with current debt. For results based on subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher.

Additional research was conducted by the Urban Institute, which analyzed credit bureau and other demographic data on poverty, race, and health status to explore where medical debt is concentrated in the U.S. and what factors are associated with high debt levels.

The JPMorgan Chase Institute analyzed records from a sampling of Chase credit card holders to look at how customers’ balances may be affected by major medical expenses.

Reporters from KHN and NPR also conducted hundreds of interviews with patients across the country; spoke with physicians, health industry leaders, consumer advocates, debt lawyers, and researchers; and reviewed scores of studies and surveys about medical debt.

I have treated numerous physicians with complex issues none of their conventionally trained colleagues could address through using alternative modalities like homeopathy and I have had numerous times where the doctor completely cut me off once I got them better. The existence of efficacious therapies outside their body of knowledge is very threatening; it makes the doctors feel diminished, and from what I’ve seen they often default to acting like the whole ordeal was a bad dream that never happened rather than to consider the possibility that their model is incomplete.

Everything looks good to me. The only flag that I saw was that PepsiCo is one of our top ten stocks (in which AND has invested). I personally like Pepsico and do not have any problems with us owning it, but I wonder if someone will say something about that. Hopefully they will be happy like they should be! I personally would be OK if we owned Coke stock!! (Donna Martin, email, 3rd January 2014)

[I] Heard an earful yesterday on the phone from Jean as President of Dairy (NDC) about our Vegetarian position paper (six months later?) that has a line in it about dairy and meat. Nothing in the paper says don’t eat dairy or meat or be a vegetarian or vegan but she was saying that Dairy is helping us with funding to elevate the Academy’s science and evidence and it’s so disappointing. I resented the correlation of the sponsorship. (Patricia Babjak, 28th April 2017)

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 168 guests