Letter from Libya

King of KingsThe last days of Muammar Qaddafi.

by Jon Lee Anderson November 7, 2011

How does it end? The dictator dies, shrivelled and demented, in his bed; he flees the rebels in a private plane; he is caught hiding in a mountain outpost, a drainage pipe, a spider hole. He is tried. He is not tried. He is dragged, bloody and dazed, through the streets, then executed. The humbling comes in myriad forms, but what is revealed is always the same: the technologies of paranoia, the stories of slaughter and fear, the vaults, the national economies employed as personal property, the crazy pets, the prostitutes, the golden fixtures.

Instinctively, when dictators are toppled, we invade their castles and expose their vanities and luxuries—Imelda’s shoes, the Shah’s jewels. We loot and desecrate, in order to cut them finally, futilely, down to size. After the fall of Baghdad, I visited the gaudiest of Saddam’s palaces, examined his tasteless art, his Cuban cigars, his private lakes with their specially bred giant fish, his self-worshipping bronze effigies. I saw thirty years’ worth of bodies in secret graves, along with those of Iraqis bound and shot just hours before liberation. In Afghanistan, Mullah Omar, a despot of simpler tastes, left behind little but plastic flowers, a few Land Cruisers with CDs of Islamic music, and an unkempt garden where he had spent hours petting his favorite cow.

During the long uprising in Libya, I toured the wreckage of Muammar Qaddafi’s forty-two years in power. There were the usual trappings of solipsistic authority—the armaments and ornaments—but above all there was a void, a sense that his mania had left room in the country for nothing else. Qaddafi was not the worst of the modern world’s dictators; the smallness of Libya’s population did not provide him with an adequate human canvas to compete with Saddam or Stalin. But few were as vain and capricious, and in recent times only Fidel Castro—who spent almost half a century as Cuba’s Jefe Máximo—reigned longer.

When is the right time to leave? Nicolae Ceausescu didn’t realize he was hated until, one night in 1989, a crowd of his citizens suddenly began jeering him; four days later, he and his wife faced a firing squad. Qaddafi, likewise, waited until it was too late, continuing to posture and give orotund speeches long after his people had rejected him. In an interview in the first weeks of the revolt, he waved away the journalist Christiane Amanpour’s suggestion that he might be unpopular. She didn’t understand Libyans, he said: “All my people love me.”

For Qaddafi, the end came in stages: first, the uprisings in the east, the successive fights along the coastal road, the bombing by NATO, the sieges of Misurata and Zawiyah; then the fall of Tripoli and, finally, the bloody endgame in the Mediterranean city of Surt, his birthplace. In the days after the rebels took over Tripoli, this August, the city was a surreal and edgy place. The rebels dramatized their triumph by removing the visible symbols of Qaddafi’s power wherever they found them. They defiled the Brother Leader’s ubiquitous portraits and put up cartoons in which he was portrayed with the body of a rat. They replaced his green flags with the pre-Qaddafi green-red-and-black. They dragged out carpets bearing his image—a common sight in official buildings—to be stomped on in doorways or ruined by traffic. At one of the many Centers for the Study and Research of the Green Book, a large pyramid of green-and-white concrete, the glass door was shattered, the interior trashed. Inside, I found a dozen copies of the Green Book—the repository of Qaddafi’s eccentric ideas—floating in a fountain.

The rebels warily took the measure of the city, investigating sealed-off areas and hunting for hidden enemies. Some were looking for the bodies of fallen friends; some wanted to punish those they believed were responsible for war crimes. As their victory became more secure, ordinary citizens began to venture out and to explore the places from which Qaddafi had ruled over them for decades.

Still, an existential unease prevailed. It was impossible to imagine life without Qaddafi. On September 1, 1969, the day that he and a group of fellow junior Army officers seized power from the Libyan monarch, King Idris, Richard Nixon was seven months into his Presidency; the Woodstock festival had taken place two weeks earlier. In Africa, despite a decade of dramatic decolonization, ten countries languished under colonial or white-minority rule. Qaddafi was just twenty-seven, charismatic and undeniably handsome. Nothing hinted at the clownish, ranting figure of later years.

As Libya’s population more than tripled, from under two million to more than six million, Qaddafi became as complete a dictator as the region had known: all-seeing, all-controlling, megalomaniacal. To the outside world, he was the Michael Jackson of global politics, an unhinged figure whose vast wealth bought him repeated indulgences for unseemly behavior. Inside Libya, his image was defined by the mechanisms and the depth of his control.

Although Qaddafi was widely despised, he was held in awe for his cunning—so much so that even after he abandoned Tripoli to the rebels many Libyans feared he was still capable of outwitting his enemies and returning to power. A former senior government official told me, “I feel like a man who was in a dark hole, who has come into the sunlight, and it’s hazy. . . . What will happen now?” He fretted about Qaddafi. “He’s a genius,” the former official said. “He’s like a fox. He’s a very dangerous man, and he still has tricks up his sleeve. I cannot be convinced he is gone until I see him dead.”

This fall, Regeb Misellati, the former head of Libya’s central bank, greeted me at his gracious house in Tripoli. Like many former officials of the regime, Misellati portrayed himself as an outsider, even a victim. “We have got rid of Qaddafi, but what are we going to do now, fight each other?” he said. “We Libyans are as if held in 1969—even intellectually, we are retarded. Those of us who travelled could learn about the rest of the world, other ideas. But for most people here there was nothing to learn except the teachings of the Green Book, and slogans—lots of slogans. There were no civil institutions, no civil society. Qaddafi did not leave anything behind except material and cultural destruction.”

Bab al-Aziziya, Qaddafi’s compound in Tripoli, was not the kind of Presidential residence that gives tours to schoolkids. Concrete blast walls, gun slits, and guard turrets sealed off Qaddafi and his inner circle from life in the capital. Inside the walls was a sprawling complex of intersecting compounds. On the entry road, a pair of old signs read, “Down, Down U.S.A.,” and “We Love Our Leader Muammar Forever.”

The most striking structure on the property was the iconic House of Resistance, where Qaddafi and his family lived until, in 1986, it was bombed by U.S. jets; the Reagan Administration attacked the compound after determining that Libya was behind the bombing of La Belle, a West Berlin discothèque frequented by American servicemen. The U.S. raid, which struck targets in Tripoli and Benghazi, killed thirty-nine Libyans, and Qaddafi claimed that his adopted infant daughter Hana was among them.

The ruined house was preserved as a symbol of Libya’s victimization by the “great powers,” and Qaddafi used it as a theatrical backdrop whenever he received foreign dignitaries and heads of state. It was here, too, that he made some of his legendary speeches. Last February, he appeared, dressed in a luxuriant brown turban and robe, and swore to hunt down the rebels “inch by inch” and “alleyway by alleyway.” Someone set a video of his performance to music, and a mocking remix, featuring a pretty girl dancing suggestively to the beat, became a viral sensation.

After the fall of Tripoli, I joined a crowd of curious Libyans streaming into the complex, which had become a destination for family excursions. Young boys came with girls in head scarves, as if on dates, and posed for pictures against the shattered building, astonished to be standing where Qaddafi had stood. People played music and danced. A man carrying a handheld video camera told me giddily, “In forty years, no Libyans could ever dream of coming here.”

Around the House of Resistance were the burned remains of several of Qaddafi’s elaborate tents—equipped with air-conditioning units, chandeliers, and green carpets—where he had held meetings with heads of state and conducted media interviews. Nearby, a black BMW 7-Series sedan was the center of some attention; its doors yawned open, revealing leather seats, walnut trim, windows of four-inch-thick bulletproof glass. Nearby, another car, entirely torched, still smoldered. Men loaded mattresses from a guardhouse onto a pickup. Everywhere, littering the ground, lay bits of festive-looking silver cardboard: discarded ammunition boxes for Beretta pistols.

Pathways led through gardens to an artificial hillock, where a disk-shaped house—Qaddafi’s residence—was built down into the earth, like a half-buried U.F.O. Libyans wandered around wearing expressions of shock. Many of them, it seemed, had believed Qaddafi’s long-standing claims of a modest salary and an austere Bedouin life style. Instead, they saw a private gym, an indoor swimming pool, a hairdressing salon. They explored a network of bombproof tunnels, built by a German company in the eighties and nineties. I climbed down a ladder under a grass-covered pillbox five hundred feet away from the House of Resistance, and, ten minutes later, I found my way inside Qaddafi’s home.

The house had already been looted and partly burned. There were ripped posters of Qaddafi underfoot; anything with his image on it had been smashed. I came across a collection of videos, most homemade and labelled by hand. Among them I spotted “Revenge,” a 1990 action-romance starring Kevin Costner, a martial-arts movie with Arabic subtitles, a video of Libyan women dancing and swinging their hair sensuously to traditional music. Another room contained family albums and portraits: Qaddafi with his children when they were young, with Nikita Khrushchev, with Condoleezza Rice. A framed certificate honored him with membership in the International Commission for the Prevention of Alcoholism.

The rebels had ransacked the wardrobes, and piles of clothes lay on the floor. I saw a man emerge from a room in a black silk robe and declare, “I am Qaddafi, King of Africa!” Indeed, trophies of the old order became fashionable around Tripoli. One evening, I saw a rebel soldier manning a roadblock with a gold-plated Kalashnikov, one of several such weapons found in Qaddafi’s residence. During a rally in Green Square, the center of protests in Tripoli, a fighter danced up next to me wearing a leopard skin, lined with green satin. He said it had come from Qaddafi’s closet, and guessed it had been a gift from a visiting witch doctor. It was an article of faith among the rebels that Qaddafi had regularly used magic to prop up his long reign. What other explanation could there be?

Photographs from the nineteen-sixties, when Muammar Qaddafi was a uniformed officer in his twenties, show a slim young man with a proud, erect carriage. (His nickname then was Al Jamil—the handsome one. By the time of his death, it had changed to Abu Shafshufa, or Old Frizzhead.) Qaddafi was born in 1942, into the al-Qadhadhfa tribe, and spent his early childhood in a Bedouin desert tent outside Surt. Libya was just emerging from a long struggle against colonial rule. Italy had invaded in 1911, and for twenty years the Libyans resisted. The Italians responded with a network of forced-labor and concentration camps that killed as much as a third of the country’s population; the revolt failed, and the Italians stayed until the British forced them out. But the resistance remained a source of national pride. Qaddafi’s father talked to him often about the fighting, in which he had been wounded and Qaddafi’s grandfather had been killed.

The family lived as nomads, and Qaddafi had no formal education until he was ten years old, and his family sent him to school in Surt. They couldn’t afford to rent a room for him, so he slept in a mosque and hitchhiked home on weekends, sometimes catching a ride on a camel or a donkey. He went to secondary school in the Saharan city of Sabha, where he developed a lifelong admiration for Egypt’s leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Nasser, an Army officer and a pan-Arabist, worked with a revolutionary group called the Free Officers to topple the monarch, King Farouk, in 1952. As President, he outraged the West by nationalizing the Suez Canal. Qaddafi also developed strong feelings for the Palestinian cause and an antipathy toward foreigners, especially the British, who had assumed military administration of Libya during the Second World War; though Libya formally acquired its independence in 1951, under the British-backed King Idris, it remained a virtual protectorate. Qaddafi got in trouble for defiantly holding up Nasser’s image in class, and was finally expelled for organizing protests.

In 1963, he entered Libya’s military academy, in Benghazi. Barney Howell, a regimental sergeant major with the British Coldstream Guards and a senior officer at the academy, remembered him as a rabble-rouser. Qaddafi would spit at Howell whenever he dared to correct him in drills. “Once or twice when this actually landed on my clothing I reported the fact, and he was then pulled up and severely punished,” Howell recalled. “This, no doubt, didn’t help his love of the Western world, but what was I to do?”

In April, 1966, when Qaddafi was twenty-three, he left Libya for the first time. With a group of young officers, he was sent to a military academy in Beaconsfield, England, for a signal-corps training course. His first encounter with a British officer there went badly; Qaddafi later described the man as a “typical ugly British colonialist,” who “hated the Arabs.” To avoid interacting with him, Qaddafi pretended not to understand English. After several days of “oppression and insults,” he and his Libyan classmates were sent on to another institute, where, as he put it, “we met some Arab brothers from Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Iraq, and we formed a solid group.”

There Qaddafi sealed himself off even further from his surroundings, putting a picture of a Bedouin tent on the wall of his room. On his first trip into London, he wore a white jird, a traditional Libyan robe, to Piccadilly Circus. In a photograph of the moment, a resolute Qaddafi strides forth in native dress, chin raised. “I was prompted by a feeling of challenge and a desire to assert myself,” he recalled. “We became self-absorbed and introverted in the face of the Western civilization, which conflicts with our values.”

Swinging London must have been a shock to the straitlaced young officer from the Libyan desert. After his sole outing, he did not venture back into the city. As he stolidly told an interviewer some years later, “I did not explore the cultural life in London,” preferring to spend his free time in the countryside. When Qaddafi’s training course was over, he hurried home. He had seen little that impressed him, and much that hadn’t. He returned, he said, “more confident and proud of our values, ideals, heritage, and social character.”

Back in Libya, Qaddafi organized an underground nationalist group, inspired by Nasser. The movement, also called the Free Officers, progressed slowly at first—holding meetings, developing “organizational procedures,” distributing a revolutionary newspaper. Within a few years, the officers realized that circumstances were in their favor. Idris was old, ailing, and seemingly uninterested in governing. In 1969, while he was out of the country, the Free Officers seized control.

Libya’s greatest historical hero was Omar Mukhtar, who was hanged for leading the resistance against the Italians. Qaddafi, in the spirit of both Mukhtar and Nasser, demanded the ouster of the British from their naval base in Tobruk and the Americans from an Air Force base on the outskirts of Tripoli. Twenty thousand Italian immigrants, remnants of a once sizable colony, were expelled and their possessions confiscated; even the bones of Italians who were buried there were later disinterred and shipped out of the country.

Idris had left a thriving oil industry, and Qaddafi, seeing an opportunity to bolster Libya’s “economic sovereignty,” set about negotiating more favorable terms with the Western oil companies. Henry Schuler, an American who represented Hunt Oil in the negotiations, told me recently, “In the end, Qaddafi won, which led him to conclude that if he pushed hard enough he’d get what he wanted.” By doing so, Qaddafi effectively quadrupled Libya’s oil income and established himself as a nationalist hero. These easy victories allowed him to cement his authority, and they set a pattern of behavior that never changed. “Qaddafi learned that every man had his price,” Schuler said, “and that’s what allowed him to stay in power for so long.”

One afternoon, as I was walking in an area on the outskirts of Tripoli referred to as “Qaddafi’s farm,” three men came up the lane. When I asked them who had lived in the villas dotted around the property, they shrugged obscurely and said, “It was all the Leader’s.”

Nearby, I visited a complex known as the Horse Club, which had also belonged to Qaddafi. The club contained a small hippodrome and, beyond it, stables. Like many of Qaddafi’s properties, it had the atmosphere of a security installation, protected by walls and a gatehouse, now abandoned. Amid the paddocks and grass was an office building, with a sign bearing a governmental title, and I asked my friend Suliman Ali Zway, a construction-materials contractor who was helping me as an interpreter, to tell me what it said. He stared at it for a long time and finally told me, “It says something like ‘The Temporary Committee of the Defense College of the Commander-in-Chief.’ ” I asked what that meant, and Suliman looked mystified. “That was one of the points about living under Qaddafi,” he replied. “It was based on confusion. We don’t know what these committees are. We never did. They all had long names, like this one, that didn’t make sense to us.”

Deliberate mystification is a common tactic of autocrats. Fidel Castro had been in power for forty years before his entourage was allowed to divulge the name of his wife, Dalia. There was also the mystery of where he lived; certain people in Havana knew that his home was on the grounds of a former country club, but those who visited never spoke of what they saw. Many Cubans believed that Fidel used underground tunnels that led out from his concealed estate, allowing him to simply appear, as if from nowhere, on the main roads of Havana.

Saddam Hussein also cultivated intense secrecy. Between his defeat in the first Gulf War, in 1991, and his ouster, in 2003, he appeared in public only a couple of times, and then in highly guarded, unannounced ceremonies. He built scores of stone-and-marble palaces around the country, and moved furtively among them, as if in a human shell game. Whenever my regime minders drove me past one, I would ask what the gigantic building was; they would fall fearfully silent, then whisper, “A guesthouse.”

Libyans had learned similar habits of willful ignorance. In the weeks after Qaddafi fled Tripoli, no one, it seemed, wanted to appear too knowledgeable about the workings of the old regime, lest they be accused of having been a part of it. In any case, Qaddafi, a master of obfuscation and conspiracy, had left few clear answers to the most basic questions. Where did he live? What went on inside those confusingly marked government buildings? What happened to all the oil money? And how was it possible that the regime had slaughtered so many political prisoners—including twelve hundred detainees in a single day, at Abu Salim prison, in 1996—and kept it secret for years? No one really knew anything for certain, it seemed, in Libya. Qaddafi had created a know-nothing state, and that, too, he had left behind.

In November, 1979, the Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci interviewed Qaddafi in Tripoli. By then, the Brother Leader had been consolidating his power for ten years, and was working to replace the previous system of Libyan law with his writings in the Green Book. The book, a slim four-inch-by-six-inch volume, contained Qaddafi’s complete guide to remaking society; along with guidelines for government and the economy, it included musings on education, black people, sports, horsemanship, and stagecraft. Fallaci, who was famous for her confrontational style, treated the book with little respect. It was “so small,” she said, that she had finished it in fifteen minutes. “My powder compact is bigger.” Undaunted, Qaddafi protested that the Green Book had taken him years to write, and that he had come to its conclusions in a state of oracular wisdom. Obviously, she hadn’t read it thoroughly, he said, or she would have grasped its central message, Jamahiriya—a word of his own invention, which he translated as “the state of the masses.”

In a chapter about political organization, he proclaimed that “parliament is a misrepresentation of the people,” and that the party system is a “contemporary form of dictatorship.” He abolished both in Libya, and replaced them with a set of local people’s committees, in which, hypothetically, everyone would participate. These smaller bodies would convey the will of the people to a General People’s Congress. To affirm that the people were in control, Qaddafi narrowed his long list of official titles to just two: Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution. Qaddafi told Fallaci that he had created a state in which “there is no government, no parliament, no representation, no strikes, and everything is Jamahiriya.” When she scoffed, he said, “Oh, how traditionalist you Westerners are. You only understand democracy, republic, old stuff like that. . . . Now humanity has passed to another stage and created Jamahiriya, which is the final solution.”

The Green Book rejected Communism and capitalism, claiming that both systems gave citizens an insufficient chance to share the country’s wealth. As part of a sweeping economic reform, Qaddafi abolished personal property, and, in 1978, announced that all factories were being handed over to the workers. Regeb Misellati, the former head of the central bank, told me, “They changed the management, removing all the managers and replacing them with revolutionary committees; they also did this in schools and hospitals. This meant that, in some cases, orderlies were appointed as managers.” Qaddafi used similarly disruptive tactics in politics, splitting Libya into ten administrative districts, then fifty-five, forty-eight, twenty-eight—each time with a complete purge of staff, so that no one except him could maintain authority for long.

The Green Book’s most succinct statement about government in Libya came from a warning about the dangers of rule by the masses: “Theoretically, this is genuine democracy, but, realistically, the strong always rules.” Husni Bey, one of Libya’s most prominent businessmen, told me that Qaddafi developed an elaborate system for exercising power while minimizing direct responsibility. “Qaddafi never wrote down anything,” he said. “He would dictate orders to secretaries, bypassing his ministers. The secretaries he dictated to formed a group called El Qalam, in which he had a representative for everything; there was one for oil, for the tribes, for security, and so forth. These people in turn would not write anything down but call the minister in question, and he would obey, knowing that the order had come from Muammar Qaddafi. In this way, the system worked, a system without ultimate accountability for anything.”

Early in his rule, Qaddafi had made clear his regime’s embrace of Nasserite pan-Arabism, its support for Palestine, and its hostility toward Israel and the “imperialist powers” of Great Britain and the United States. By the early seventies, the U.S. had withdrawn its ambassador. Qaddafi, having cut himself off from the West, began buying weapons from Moscow. As he built his Army, he purchased hundreds of fighter jets and tanks; through a pair of rogue C.I.A. agents, he acquired tons of plastic explosives.

Qaddafi seemed determined to provoke outrage, particularly in his support for the Palestinian cause. In 1972, he applauded the terrorist attacks at the Munich Olympics, in which eleven Israelis were murdered; indeed, he was believed to be a sponsor of Black September, the Palestinian group that carried out the attacks. He proclaimed Libya a sanctuary for anyone who wanted training to fight on behalf of the Palestinians. Many came, including the notorious terrorist Abu Nidal. Qaddafi also gave financial support to the Provisional I.R.A., the Italian Red Brigades, the Venezuelan assassin Ilich Ramírez Sánchez (better known as Carlos the Jackal), and guerrilla groups in Africa, Latin America, even the Philippines. In the seventies, Qaddafi sent assistance to the Sandinistas, in Nicaragua. When the renegade Sandinista Eden Pastora, known as Commander Zero, fell out with his comrades, he went to Libya to ask Qaddafi to back a counter-revolution. Pastora later told me that the Libyan leader had heard him out but wasn’t interested in his plans. He had, however, offered him five million dollars to spread the revolutionary cause in Guatemala.

For some unpopular causes, Qaddafi offered a last resort. Months before Fallaci arrived, he intervened in Uganda to protect the dictator Idi Amin from invading Tanzanian troops and, later, spirited him away to a house near Tripoli. In the interview, Qaddafi defended Amin. Although he allowed that he might not like the Ugandan despot’s “internal policies”—which included torture and mass murder—he was a Muslim and he opposed Israel, and that was all that mattered.

The British journalist Kate Dourian, who travelled to Libya frequently during the eighties, told me that Qaddafi seemed to grow increasingly untethered from reality. It was an effect of his unchecked power, she suggested, amplified by the media attention he received. “He was invariably described as ‘strikingly handsome’ in the first paragraph of every piece written about him, and it had probably gone to his head,” she said. “He’d fly us into the desert to see the Great Man-Made River,” his multibillion-dollar project to channel water from a Saharan aquifer to the cities along the coast. “Then he’d leave us there—journalists, diplomats, officials—until the sun was right, so that he could appear on his horse with the sun at the right angle.”

The ethos of Jamahiriya was purportedly feminist, but Qaddafi had peculiar attitudes toward women. In the Green Book, he wrote about them from a nearly zoological remove: “Women, like men, are human beings. This is an incontestable truth. . . . According to gynecologists women, unlike men, menstruate each month.” Although he abolished the stricture against women having driver’s licenses, he later explained that the law was redundant, because women’s fathers and husbands could make that decision for them. He was tended to by nurses he brought in from Ukraine, and for years he kept a squad of female bodyguards, the Revolutionary Nuns. Qaddafi claimed that using female guards proved his devotion to feminism. Others said he believed that Arab men wouldn’t shoot women.

After the Berlin discothèque bombing, in 1986, Dourian attended a press conference in Tripoli, and she recalls that Qaddafi spent most of it checking out the women in the audience. “He wore a supercilious look, scrutinizing us, and then looking down and taking notes,” she recalled. “We later realized that he was picking the women he liked and describing them to his aides so they could identify us.” After the conference, she left on a bus with other journalists. “The bus was stopped, and someone got on and said I should come with him.” She was taken to Bab al-Aziziya, where Qaddafi was waiting with several other Western women he had selected. “He looked up and said, in Arabic, ‘Here’s the one I want.’ Then he pointed to another woman”—a brunette, like Dourian—“and said, ‘She looks like a Bedouin. I can’t decide which one I like.’ ”

Qaddafi spoke about Western books and music he admired: “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” “The Outsider,” Beethoven’s symphonies. At one point, he asked the other brunette to go with him to an adjoining room. Later, the woman told Dourian that he’d grabbed her, and declared his love and his wish to marry her.

A week later, Dourian and the other women met Qaddafi at a family gathering, held in a tent. He wore a long, flowing cape with a salmon-colored headdress. His wife, Safia, was there, with the children.

“Eventually, he sent the family away and said to us, ‘Let’s go for tea,’ ” Dourian said. They returned to Bab al-Aziziya, where he disappeared for a while and returned in a different outfit. “It was the most extraordinary thing, an après-ski jumpsuit, powder blue, padded,” Dourian said. “He looked at me, and said, ‘Come.’ He grabbed me by the hand and we went into a room without a light. There was just a double bed, and a TV that was switched on. I remember it was him on the TV; there was only one channel, and all it ever showed was him. He threw himself down on the bed and said, ‘Come and sit.’ He gently tried to pull me down with him, and I pulled myself back. He asked, ‘Are you a girl or a woman?’ He was trying to find out whether I was a virgin. I said I was a girl, and told him that not every Western woman is promiscuous.”

Dourian tried to distract Qaddafi by talking about her Armenian heritage, politics––anything but the subject at hand. “He asked about Ronald Reagan, whom he seemed obsessed with, and wanted to know if he was really popular,” she said. “He wasn’t well travelled at that time; I felt as if you had to explain things to him as you would with a child. He had surrounded himself in this little fantasy world, but there was a naïveté about whatever lay outside of it.”

Finally, Dourian asked to leave, saying that her friends would wonder what was happening. As they stood to go, Qaddafi suggested that she shouldn’t be embarrassed. “He smacked me a kiss on the forehead and said, with a laugh, ‘The Armenian resistance—very strong.’

For the first decades of Qaddafi’s rule, the Jamahiriya was in certain respects an improvement for many Libyans. In a country where more than eighty per cent of the population had been illiterate, a program of free education, up to the college level, helped push the literacy rate above fifty per cent. Medical care, if rudimentary by American standards, was free. The average annual salary, which had been two thousand dollars under King Idris, rose to ten thousand dollars. All these programs were underwritten by the increasingly rich oil economy. The worldwide oil crisis of 1973 sent prices soaring, and Libya made a fortune. Qaddafi funnelled money and jobs to his citizens, through patronage, infrastructure projects, and a public sector that at one point employed three-quarters of the working population.

But Qaddafi’s ban on private enterprise created many food and commodity scarcities; bananas, for instance, became a prized luxury. David Sullivan, a private investigator from San Francisco, worked for a contractor in Libya, setting up telecommunications systems around the country. “Nearly all work was done by foreigners.” he said. “Jobs were classified by nationality, with black Africans at the bottom of the ladder. They lived in shipping containers along the side of the road. Libyans spent their days idling in tea shops with nothing to do, all of them on the dole. Qaddafi decided one day that men idling in tea shops gave the impression that Libyans were lazy, so he decreed they be shut. I was buying a tea one day when the order was enforced—without any notice, of course. Trucks pulled up with soldiers who started beating everybody and smashing up the tables and crockery.”

Sullivan came away convinced that Qaddafi was a madman who had turned Libya into an insane asylum. “One day, driving into Tripoli, I saw dead camels everywhere,” he recalled. “Qaddafi had decided that having camels within the city limits made Tripoli look like a backward place. Since he was trying to become the head of the Organization of African Unity, that wasn’t a good thing, so he had all camels shot that were on the road into the city.”

That mix of paternalism and violence was typical. As one former Libyan diplomat told me, “The ideology of the regime was not convincing at all, but the terror was very efficient.” Qaddafi’s secret police and revolutionary committees nurtured a comprehensive network of informants, set up with the help of the East Germans. A former intelligence officer described the process: “We would be given the names of civilians. Then we would move people around to surveil the person and also use technical surveillance—wiretaps and so on. By the time the file got to the director, there would be enough information on that person to become his best friend.”

Recalcitrant students and political dissidents were picked up, tortured, given show trials, and either imprisoned or hanged. The hangings often took place on the grounds of universities, with fellow-students and parents forced to watch. An especially vivid and exemplary execution came in 1984, when a young man named Sadiq Hamed Shwehdi was tried in Benghazi’s basketball stadium on charges of terrorism. Hundreds of schoolchildren were bused in to attend, and the trial was broadcast live on national television. Shwehdi, on his knees, wept as he confessed to joining the “stray dogs”—Qaddafi’s term for his exiled opponents—while he was studying in the United States. A panel of revolutionary judges sentenced him to death, and he was led to a waiting gallows. Shwehdi hung from the noose, slowly strangling, until suddenly a young woman in an olive-green uniform, a “volunteer” named Huda Ben Amer, strode up and violently pulled on his legs. Qaddafi rewarded Ben Amer for her show of revolutionary zeal, and she later served two terms as the mayor of Benghazi.

In Tripoli, I met Mohamed El Lagi, a bombastic man in his fifties who had been a senior internal-affairs officer in the Army before secretly switching sides, this summer. While still working for the regime, he began coöperating with the Omar Mukhtar Brigade, a Benghazi-based rebel force. At a walled compound on the outskirts of the city, El Lagi was helping to operate a kind of defectors’ clearing house. A stream of men came in, some who had been captured or had surrendered, and some who had been summoned by El Lagi. In back rooms, they were debriefed and then pressed to bring in other former members of the regime. El Lagi chain-smoked Marlboro Reds and was unshaved and anxious. When we met, he hadn’t slept for days. Still afraid of the old regime, he told me that under Qaddafi he helped compile intelligence reports on the Libyan Army. “There was no real interest in the state of the Army itself,” El Lagi said, “but if I reported about someone being critical of Muammar Qaddafi all hell would break loose.”

A couple of large cardboard boxes, full of reel-to-reel tape recordings, sat on the floor. El Lagi said that they were secretly recorded tapes of Qaddafi’s meetings. “This one is a surveillance tape of visiting African leaders,” he said, picking one up, “and this one, from 2009, was made inside the President’s palace in Chad.” He laughed and exclaimed, “This was Qaddafi! He had intelligence everywhere!”

Libyans occasionally fought back against this repression, and, over the years, Qaddafi survived at least eight serious coup plots and a number of assassination attempts. One evening in late August, at a victory rally in Tripoli’s Old City, an elderly woman in a black abaya came up to me, holding a black-and-white photograph of a military officer. She introduced herself as Fatma Abu Sabah, and said that the photograph was of her late husband, who had been a member of Qaddafi’s old revolutionary group, the Free Officers. In 1975, she explained, a group of officers, including her husband, planned a coup. “They thought Qaddafi had veered away from the principles of the revolution,” she said. Before they could execute the plan, they were betrayed by a fellow-officer, a general in Qaddafi’s regime, and taken into military custody.

There were two trials, Fatma explained. In the first, the condemned officers were given life in prison. When they appealed, they were sentenced to death, and twenty-two of them—including her husband—were executed by firing squad. She told me, “We don’t know where he is buried, and we were prohibited from having a mourning period.” She was ejected from her home, along with her daughters, aged one and three. “They put red wax on the door, sealing it, so that no one else could enter.”

To the extent that Libyans could imagine a future beyond Qaddafi, they often wondered who would replace him when he died. In much of North Africa and the Middle East, power is dynastic, and the leader is customarily expected to hand off power to his son; in Syria, Bashar al-Assad took over for his father, and, in Egypt, Gamal Mubarak was expected to take over for his. In Libya, the calculus was complicated: Qaddafi had nine living children, and all but one of them were sons. Muhammad, the eldest, was born in 1970, to Qaddafi’s first wife, Fatiha. Shortly afterward, Qaddafi divorced Fatiha and married Safia, a nurse, with whom he had six boys and a girl: Seif al-Islam, Saadi, Hannibal, Aisha, Muatassim, Seif al-Arab, and Khamis. They adopted a seventh boy, Milad.

Most of the Qaddafi offspring enjoyed lucrative sinecures at the agencies that dominated Libyan telecommunications, energy, real estate, construction, arms procurement, and overseas investments. Several of the sons had advisory roles that were vaguely defined but gave them powers vastly greater than those of official government ministers. Khamis commanded Libya’s élite military corps, the Khamis Brigade, which led a four-month siege of Misurata that killed more than a thousand civilians. Muhammad ran the General Post and Telecommunications Company, which owned the monopoly on satellite- and cell-phone services. Hannibal held a senior position at the Libyan Maritime Transport Company, handling oil shipments. Libya was less a nation than it was a thriving family business.

Still, Qaddafi often seemed more interested in playing his children off against one another than in developing a legitimate successor. Not that he had many good options. Saadi, the third son, had a reputation as a hard-partying bisexual and a dilettante entrepreneur. His father, distressed by his life style, gave him control of a military brigade, but he wasn’t interested. Instead, he played briefly on an Italian soccer team—until he was suspended on suspicion of doping—and then formed a movie-production company called World Navigator Entertainment, which raised a reported hundred million dollars to finance movie projects in Hollywood. Laura Bickford, an American movie producer, told me that Saadi’s company had offered her financing, which she ultimately declined. “When you’re an independent film producer looking for equity, you can find yourself talking to a dictator’s son,” she said. “But taking money from the son of the man who ordered the Lockerbie bombing was too much.”

Muatassim, who was tall and fashionably long-haired, competed with Saadi as a hedonist, and with Seif al-Islam, the second son, for his father’s trust as a security adviser. In 2009, Muatassim threw a New Year’s Eve party on St. Bart’s, and hired Beyoncé and Usher to perform for his friends. After Libya’s uprising began, Beyoncé’s publicist announced that she had donated her fee, a million dollars, to Haiti’s earthquake victims.

Toward the end of the decade, it became clear that Seif al-Islam—“sword of Islam”—would be his father’s heir. For years, he had lived in London, where he partied in Mayfair’s most fashionable clubs and acquired an entourage of facilitators in all walks of British society. In 2008, he was awarded a doctoral degree in political philosophy from the London School of Economics; soon afterward, he pledged to give the school $2.2 million, through a charitable foundation in his control. Seif advertised himself as a “reformer,” open to Western ideas and investment—a kind of rational balance to his father’s lunatic image. He played a key role in negotiations with the West, sponsored a political opening for his father’s domestic opponents, and arranged an amnesty for imprisoned dissidents. He set up a foundation to promote his views, arranged junkets to Libya for the foreign press, and argued in favor of modernization and openness; he sometimes criticized his father, and then fell out with him, ostensibly for not initiating reforms quickly enough.

But if Seif was genuinely interested in liberalization his father was not. Ashour Gargoum, a former Libyan diplomat, worked on a human-rights commission that Seif funded. After the Abu Salim massacre came to light, he said, Seif sent him with a delegation to London to meet with Amnesty International, which was calling for an investigation into the killings. “Muammar Qaddafi wanted a report from me about this,” he said. “I spoke to him in a tête-à-tête, using words that I knew he would accept. I phrased it ‘the Abu Salim problem,’ and I said, ‘We need to resolve it,’ this kind of language. He said, ‘But we have no political prisoners.’ I said, ‘Yes, we do.’ He said, ‘But they are heretics’ ”—meaning radical Islamists. “ ‘They have no rights.’ ”

In the end, Seif’s reformist equanimity seemed to abandon him. Shortly after the uprising began, he appeared in a video waving a weapon in front of a shouting mob of supporters. Promising to defend the regime to the death, he predicted that “rivers of blood” would flow in Libya. The L.S.E. is investigating charges that Seif’s doctoral dissertation was ghostwritten; the dean resigned. The university said that it would distribute that portion of Seif’s gift which had already been paid, about half a million dollars, into a scholarship fund for students from North Africa, and refuse the rest. By June, Seif, along with his father, had been indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Court.

Qaddafi’s children owned urban villas, beach houses, and countryside retreats, and as these houses were breached looters encountered unimaginable decadence: state-of-the-art gyms, Jacuzzis, exotic cars, private zoos. Although the family patriarch banned alcohol in 1969, many of the Qaddafi children had well-stocked liquor cabinets. Aisha’s house in Tripoli had a love seat set into a gilded sculpture of a mermaid fashioned to resemble her. Seif’s house had cages for his pet white tigers. There were lacquered shopping bags from Versace, Hermès, Rado, Louis Vuitton, Cartier, La Perla. The children’s homes, like their father’s, had networks of tunnels, with medical clinics, furnished bedrooms, and offices, all spotlessly clean, awaiting the final retreat.

Saadi’s mansion, a few miles outside of town, was perhaps the most indulgent. It was set in about ten acres of olive and orange groves, surrounded by sliding stone walls on electronic tracks, which allowed the house to be shut up like a fortress. The main house was arrayed in a V around a vast swimming pool with a central island attached to the house by a hydraulic drawbridge. When I visited, this fall, a long-stemmed red rose lay in the empty pool, along with the cardboard container for a bottle of Laurent Perrier pink champagne. A few minutes’ walk away was a party house, featuring a forty-foot bulletproof-glass sphere topped with a gold-and-turquoise crown. A Libyan man, also touring the property, remarked with disgust, “So this was owned by a man on a four-hundred-and-seventy-five-dinar salary.”

Next door, in curious juxtaposition, was a facility called the African Center for Infectious Disease Research and Control. Fighters manned a roadblock there, and a few of them hopped into a car and urged me to follow them. Five minutes away, in a forested area off the main road, they showed me several twenty-foot Soviet-era anti-ship cruise missiles that had been concealed among the trees. The fighters were anxious about the missiles, because they were unguarded. Believing the man they had overthrown to be capable of anything, they worried that these might be chemical weapons.

The better-known escapades of the Qaddafi sons involved living it up at the Cannes Film Festival and paying handsomely to be entertained by foreign pop stars. But at least one of them, Hannibal, showed a penchant for sadism reminiscent of that of Uday, Saddam Hussein’s psychotic older son. During one recent visit to Tripoli, I went to the Burns and Plastic Surgery Hospital to meet a thirty-year-old Ethiopian woman named Shweyga Mullah. For a year, she had been a nanny for Hannibal’s children, and was now healing from fourth-degree burns inflicted by Hannibal’s wife, Aline, a Lebanese former model. A doctor showed me to Shweyga’s room, where she was in bed, with an I.V. drip attached to one of her arms. There was an odor of burned flesh. The doctor told me that she had been brought in by a Qaddafi security guard, who ordered the doctors to register her as Anonymous.

“She’s burned everywhere,” the doctor said. Shweyga was fragile, but she was conscious. In a shy voice, she told me that, before she worked for the Qaddafis, she had lived with her parents in Addis Ababa. She was unmarried, and her father was often away, working as a farm laborer. The Libyan Embassy was looking for domestic workers, so she applied and was hired to go to Libya and work for the Qaddafis. Unknown to her, the two had a reputation for violence. In 2008, they were arrested by Swiss police after employees at the President Wilson Hotel, in Geneva, reported that Hannibal and Aline had beaten them with coat hangers. The Qaddafis were quickly released on bail, but, in retaliation, Muammar Qaddafi detained two Swiss businessmen for more than a year, withdrew billions of Libyan dollars from Swiss banks, and suspended oil shipments to Switzerland. The Swiss President, Hans-Rudolf Merz, was finally forced to fly to Tripoli and issue a public apology for the “unjustified arrests.”

When Shweyga first arrived at the Qaddafis’ home, she said, “I was scared, because I saw Hannibal’s wife slapping people.” The head of the domestic staff, though, told her not to worry—Aline wouldn’t harm her. She was put in charge of the Qaddafis’ two children, a boy of six and a girl of three. Aline, she said, led a cosseted life—“she read magazines, watched TV”—and didn’t like to be disturbed. “She’d hit me if her children cried,” Shweyga said. She thought of running away, she said, “but there was no escape.”

One morning, she said, “I was gathering up her son’s clothes, but I didn’t do it properly. So for the next three days she made me stand in the garden. I wasn’t allowed to eat or to sleep.” When Aline allowed Shweyga back inside, she went to the kitchen, thirsty after her ordeal, and drank some juice. “The wife came and said, ‘What are you doing here?’ She accused me of eating some Turkish delight. I insisted that I hadn’t. She called me a liar.” The next morning, Aline told the other servants to tie Shweyga up, and to boil some water. “They tied my legs and tied my hands behind my back. I was brought into the bathroom and put in a bathtub, and she started pouring the boiling water on me, over my head. My mouth was taped, so I couldn’t scream.” Hannibal was there, she said, but he did nothing. Shweyga was left in the bathroom, tied up, until the next day. “It was too much pain,” she said. After about ten days, the security guard secretly took her to the hospital, but Aline found out. “She said if he didn’t bring me back he’d be imprisoned, so he brought me back.” Only after Aline fled Tripoli was Shweyga taken again to the hospital. She had been there ever since.

Outside the room, the doctor told me that she would probably survive, but she would need ongoing plastic surgery. “Her life is ruined,” he concluded. Enraged by Aline’s cruelty, he said, “The same that she did to Shweyga should be done to her.” Aline is now in exile in Algeria, as is Hannibal. Indeed, most of the Qaddafi children have fled to safety. Seif al-Arab and Khamis are said to have been killed in the uprising. On October 20th, Muatassim was executed with his father.

As Qaddafi’s revolution metastasized into a dictatorship, he never abandoned Nasser’s hope for a unified Arab state. Over the years, he tried to merge Libya with a number of its neighbors—Tunisia, Egypt, Syria—but these “Arab unions” were invariably short-lived. In frustration, he chastised other Arab leaders for not doing enough to help the Palestinians, and for currying favor with the West. After the P.L.O. attended the Oslo peace talks with Israel, he expelled thirty thousand Palestinian immigrants from Libya.

If the Arab states couldn’t be united, there was at least the prospect of hegemony in Africa. Qaddafi gave out vast quantities of money and weapons to a bewildering array of revolutionary causes in sub-Saharan Africa. He also supported the fight against apartheid in South Africa. In 1997, Nelson Mandela appeared in Tripoli to proclaim that Libya’s “selfless and practical support helped assure a victory that was as much yours as it is ours.”

In the mid-seventies, Libya and Chad began a long-running conflict over a uranium-rich piece of borderland called the Aouzou Strip. In 1987, Qaddafi’s forces were finally outgunned by local soldiers backed by France and the U.S. He lost seventy-five hundred men—a tenth of the total force—and a billion and a half dollars of military equipment. Ashour Gargoum, the former Libyan diplomat, told me that the Chad episode was “a disaster for Qaddafi.” Having set out with ambitions of regional unification, he had shown himself unable to manage even his weaker neighbors. Afterward, Gargoum said, he grew “paranoid and detached from reality.”

In the nineteen-eighties, Qaddafi was a significant sponsor of terrorism in the West. Libya was linked to a series of attacks: the hijacking of the Achille Lauro cruise ship; bombings in the Rome and Vienna airports; the attack on the discothèque in Berlin. President Reagan, who publicly called Qaddafi a “mad dog,” sent the U.S. military to Libya, first shooting down two fighter jets off the coast of Tripoli and later launching the air raid that shattered the House of Resistance.

Just before Christmas, 1988, a Pan Am jet flying from London to New York was passing over the small town of Lockerbie, Scotland, when a bomb hidden in the baggage compartment exploded. The two hundred and fifty-nine passengers on board, most of them Americans, were killed, as were eleven people on the ground. In the subsequent investigation, two Libyan agents were accused. Qaddafi called the allegations “laughable,” and refused to extradite the suspects. Libya became a pariah state.

It took some time, but the United Nations and the United States passed a series of incremental sanctions, which halted Libya’s international trade, froze the country’s bank accounts, and prevented Libyans from travelling abroad. While the sanctions failed to put Qaddafi out of office, the economy stalled, and his system of patronage grew weaker. El Lagi, the former Army internal-affairs officer, told me that he started questioning the regime when women, in desperation, began to work as prostitutes. “In Tripoli, you could pick up Libyan women for ten dinars!” he said. “The gap between Qaddafi’s close family and his clan and the rest of us was huge. They had villas, health care abroad, overseas educations, all paid for by the government. But a Chad war veteran wouldn’t get anything comparable.” The Green Book, he realized, was “a failed theory.”

In 1999, Qaddafi finally agreed to hand over the Lockerbie suspects, to be tried in the Netherlands under Scottish law. One of the two suspects was found not guilty; the other, Abdel Basset al-Megrahi, was convicted, and eventually sentenced to a minimum of twenty years in a Scottish prison. Many legal observers argued that the prosecution’s case was flawed and that the trial was unduly influenced by politics. But, perversely, the case played a role in Qaddafi’s reconciliation with the West. After the trial, he announced that Libya would no longer support terrorist organizations. And when the United States invaded Iraq, in 2003, he saw an opportunity. He revealed his own nuclear-weapons procurement program and chemical-weapons facilities, and offered to dismantle them in exchange for an end to sanctions. Accepting “responsibility,” if not actual guilt, for his involvement in terrorism, he agreed to make amends for Lockerbie, and he quietly paid nearly three billion dollars in damages to the victims’ families.

A long-standing foe of Islamist radicals in Libya, Qaddafi also began collaborating with the West against Muslim extremists. Intelligence documents that I saw in Tripoli this summer revealed a cozy relationship between Qaddafi’s intelligence services and the C.I.A. and M.I.6, which permitted extraordinary rendition of Libyan suspects. In a letter from 2004, the British counterterrorism chief, Mark Allen, wrote confidingly to his Libyan counterpart, Moussa Koussa, about the recent rendition of an Islamist fighter known as Abu Abdallah: “Amusingly, we got a request from the Americans to channel requests for information from Abu Abdallah through the Americans. I have no intention of doing any such thing. . . . I feel I have the right to deal with you direct on this and am very grateful to you for the help you are giving us.” Allen—now Sir Mark—has left government and works as an adviser for BP. Abu Abdallah, whose real name is Abdel Hakim Belhaj, spent seven years in prison, and is now the military commander of Tripoli for the rebels’ National Transitional Council.

By 2004, the sanctions had been lifted. Embassies reopened; business deals were signed; oil flowed. Tony Blair and Nicolas Sarkozy came calling. Silvio Berlusconi agreed to pay reparations of five billion dollars for the harm his country had inflicted on Libya; in a meeting of the Arab League in Surt, he kissed Qaddafi’s hands.

The Americans, too, began to reconceive the “mad dog” as an ally. In April, 2009, Hillary Clinton hosted Qaddafi’s son Muatassim at the State Department, and declared herself to be “delighted” by the visit. A few months later, a congressional delegation led by Senator John McCain visited Libya and reportedly promised to help with its security needs. After a late-night meeting in Qaddafi’s tent, McCain tweeted, “Interesting meeting, with an interesting man.” In Washington, Qaddafi hired the Livingston Group, a prominent lobbying firm, to work for his interests. A confidential report from August, 2008, outlined a plan to, among other things, “begin the process of easing U.S. export restrictions regarding military and dual-use materials.” That same year, after controversial negotiations, Megrahi, the Lockerbie bomber, who had prostate cancer, was released on “compassionate grounds” and flown to Tripoli on Qaddafi’s jet. He was given a hero’s welcome in Libya, where he still lives.

Earlier this month, I spoke to a wealthy Western businessman who was close to the Qaddafis. When I arrived at his palatial home in England, he was taking a call from an Arab friend. “Kareem, how are you?” he exclaimed. He told the caller that he had a visitor and would have to talk later, but he wanted him to understand that he was now “firmly with my friends in the N.T.C.” He told me that he hoped the new order would allow him room to operate. But in his experience, he explained, Qaddafi’s Libya hadn’t been all that bad. “The worst thing Qaddafi really did was that Abu Salim thing,” he said, referring to the 1996 massacre. “I mean, killing a bunch of prisoners in the basement of a prison, that’s not nice, but, you know, these things can happen. All it takes is for someone to misinterpret an order—you know what I mean? Yes, the students were hanged in the seventies, and there was Abu Salim, but there was not much else. The secret police was around, but it wasn’t too obtrusive. If you got thrown in prison, they allowed your family to visit and bring you couscous.”

In September, 2009, Qaddafi made his first appearance at the U.N. General Assembly. He rambled and ranted for ninety-six minutes, blasting the U.S. for its history of foreign intervention, calling for new investigations into the assassinations of J.F.K. and Martin Luther King, Jr., and speculating that swine flu had been developed as a biological weapon. Along the way, he tore up the U.N. Charter and waved his copious notes wildly in the air. It was embarrassing behavior, but, given Qaddafi’s reputation for eccentricity—and his perceived usefulness as an ally against Muslim extremists—it did little damage to his international image, and the American government made no comment. At home, his hold on power seemed secure.

El Lagi said to me, “With all due respect to the Americans, they are liars. . . . The Americans go around talking about human rights, but they hosted him—they didn’t arrest him. He pitched his tent on Donald Trump’s land! The Americans received Seif and Muatassim and hosted them for three weeks in the United States as friends.” Qaddafi, meanwhile, took every opportunity to taunt the West, often in ways that Western observers didn’t understand. El Lagi said, “At the U.N., he wrote, on a blank piece of paper, so that the TV cameras could pick it up, ‘We are here.’ This was intended for us Libyans to see. And, when Tony Blair came, Qaddafi showed him the sole of his shoe; this was a sign of disrespect, and was shown on YouTube all over Libya. When Condi Rice came, he refused to shake her hand, and later, during their talk, he handed her a Libyan guitar, as if to tell her to sing. She should have left the minute he refused to shake her hand, but she didn’t. The interests of the American companies prevailed. All these gestures were deeply disappointing to Libyans, because we knew it meant he could buy anyone.”

Qaddafi always insisted that he would fight and die in Libya, and he was true to his word. After Tripoli fell, he vanished, and there was speculation that he had escaped into the Sahara, and was being protected by Tuareg tribesmen. But on October 20th, on the western edge of his home town of Surt, he and his last remaining forces, a bodyguard of a hundred or so men, were finally encircled by N.T.C. fighters. Travelling fast, in a convoy of several dozen battlewagons, they escaped to a traffic circle two miles outside Surt, and there they came under fire. As they turned to fight, in a trash-strewn field, a French warplane and an American Predator drone flew overhead and bombed them where they stood; twenty-one vehicles were incinerated and at least ninety-five men were killed. Qaddafi and a few loyalists made it into a pair of drainpipes buried in the earthen berm of a road.

They were tracked down by a group of fighters from the Misurata unit. After an exchange of fire, one of Qaddafi’s men emerged from the pipe to plead for help: “My master is here, my master is here. Muammar Qaddafi is here, and he is wounded.” Salim Bakir, one of the Misuratan fighters, told a reporter afterward that he approached the drainpipe and was stunned to see Muammar Qaddafi there. As the rebels dragged him from the drain, they said, he looked dazed and repeatedly asked, “What’s wrong, what’s happening?” Fighters came running to see the captured Leader; a mob of men shouted “Muammar!” Several had camera phones, and their jerky footage composes a chilling account of what happened next.

Qaddafi, his hair unkempt, bleeding from a wound on the left side of his head, is hustled up the dirt embankment. On the way, a fighter comes up from behind and appears to violently thrust a metal rod into his anus. On the road, the rebels pin Qaddafi down on the hood of a Toyota truck. A throng of screaming men clamor to see him, insult him, hurt him. One strikes him with his shoes, saying, “This is for Misurata, you dog.” Qaddafi is hauled to his feet, bleeding more heavily, and weakly tries to defend himself as rebels reach in to strike at him. The video devolves into chaos: someone saying, “Keep him alive,” a hand holding a pistol, boots, a baying scream of “Allahu akbar! ” He is yanked by his hair. We hear the firing of a gun.

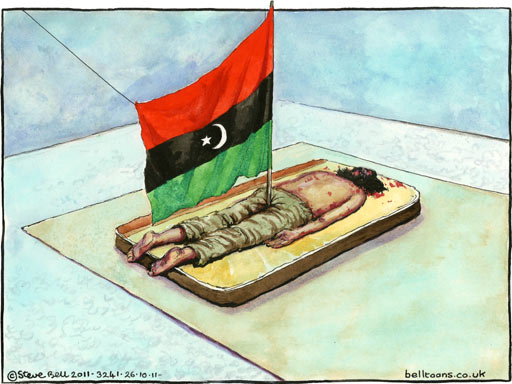

The next time we see Qaddafi, he is lying on the ground, his head lolling back, eyes half-open but unseeing. His tormentors are pulling at his shirt, rolling him over to strip him. In another image, we can see clearly that someone has shot him in the left temple. That was the official cause of death given by the examining doctor in Misurata, where Qaddafi’s body lay on view for days in a refrigerated locker, while thousands of people filed by, snapping pictures. The leaders of the N.T.C. announced that Qaddafi died of his wounds “in a crossfire” as he was being transported to the hospital; one of them even suggested that Qaddafi’s own people shot him. No one believes it. The images are there, and they tell a different story.

Most fitting, perhaps, is the version told by the young commander of the Misurata force that found and killed Qaddafi. In the drainpipe, the King of Kings was revealed to be a confused and wounded old man, without even the comfort of his customary Bedouin cap to hide his bald spot. But, the commander observed with a kind of grudging respect, right up to the end Qaddafi still believed that he was President of Libya. ♦