Ruin lust: our love affair with decaying buildingsAs much-admired photographs of decayed Detroit go on show in London, Brian Dillon charts the history of a literary and artistic obsession with ruins, from Marlowe to The Waste Land to Tacita DeanBrian Dillon

guardian.co.uk, Friday 17 February 2012

Early in May 1941, the novelist and essayist Rose Macaulay was staying at the Hampshire village of Liss, attending to family arrangements following the death of her sister Margaret. On the 13th she returned to London – since the start of the war she had lived in a flat at Luxborough House, Marylebone, and worked as a voluntary ambulance driver – and discovered that her home and all her possessions had been destroyed in the bombing a few nights before. In a letter to a friend and literary collaborator, Daniel George, she wrote: "I came up last night … to find Lux House no more – bombed and burned out of existence, and nothing saved. I am bookless, homeless, sans everything but my eyes to weep with … It would have been less trouble to have been bombed myself."

The loss of her flat, and especially the destruction of her library, had a profound effect on Macaulay: it was a decade before she completed another novel. In 1949, she lamented: "I am still haunted and troubled by ghosts, and I can still smell those acrid drifts of smouldering ashes that once were live books." But her memory of the blitz also nurtured a fascination with destruction, decay and the ambiguous emotions conjured by the sight of buildings and entire cities reduced to rubble. In 1953 Macaulay published Pleasure of Ruins, a lively and eccentric history of the "ruin lust" that gripped European art and literature in the 18th century, reached its height in the romantic period, and had apparently declined in the first half of the 20th century in the face of wreckage that could not be turned to aesthetic or nostalgic advantage.

The story that Macaulay tells in Pleasure of Ruins is essentially a modern one: it is still alive today in photographs of post-industrial Detroit and recent responses by the likes of Iain Sinclair and Laura Oldfield Ford to the demolitions wrought in the name of the London Olympics. The taste for heroic destruction or picturesque decay cannot thrive without a sense of progress for which it fulfils the role of brooding, sometimes gleeful, unconscious. There were few if any classical or medieval enthusiasts of ruination. Even in renaissance painting, which is littered with mouldered remnants of Greco-Roman statuary and architecture, ruins are ancillary to the main pictorial event, providing a fractured backdrop to a serene madonna, or a handy bit of broken column to support a wilting St Sebastian. But by the 16th and 17th centuries, Macaulay wrote, something like the later literary and artistic obsession with ruins is in the air: Shakespeare and Marlowe inhabit "a ruined and ruinous world" of blasted heaths and crumbling castles, and there are resonant examples in Webster's The Duchess of Malfi: "I do love these ancient ruins: / We never tread upon them but we set / Our foot upon some reverend history."

It was in the 18th century, however, that the ruin arrived centre-stage in European art, poetry, fiction, garden design and architecture itself. A cult of melancholy collapse and picturesque rot took hold, especially of the English aristocracy, for whom no estate was complete without its mock-dilapidated classical temple, executed in stone, plastered brick or even (as the garden designer Batty Langley advised in 1728) cut-price painted canvas. The craze inspired some well-known architectural absurdities: in Westmeath in 1740 Lord Belvedere built a ruined abbey to block the view of a house where his ex-wife had taken up with his brother, and in 1796 William Beckford first contrived his fantastical Fonthill Abbey, "a sort of habitable ruin", according to Macaulay – "sort of'" because the thing kept falling down.

Alongside such follies there flourished a literature of pleasing desuetude, encompassing aesthetic theory, romantic poetry's rubble-strewn excursions and the dank precincts of the gothic novel. In his Elements of Criticism of 1762, Lord Kames had approved ruins, real or confected, for their embodying "the triumph of time over strength, a melancholy but not unpleasant thought". And the English romantics took to ruination with a paradoxical energy, Wordsworth uncovering his poetic self among the remnants of Tintern Abbey, Coleridge in the unfinished "Kubla Khan" deriving a whole aesthetic of the literary fragment out of his botched architectural fantasia.

If all of this seems like so much picturesque maundering, it was also evidence of a fretful modernity. It was in painting that the vexing timescale of the ruin was most accurately broached – ruins, it seemed, spoke as much of the future as of the classical or more recent past. For sure, romantic art is dominated by the sublime vistas of Caspar David Friedrich, whose lone figures look dolefully on the vacant arches of medieval abbeys. But the gaze might as easily be turned on catastrophes to come: in 1830 Sir John Soane commissioned the painter Joseph Gandy to depict his recently completed Bank of England in ruins. In France, Hubert Robert had already painted the Louvre in a state of collapse, prompting Diderot to write: "The ideas ruins evoke in me are grand. Everything comes to nothing, everything perishes, everything passes, only the world remains, only time endures."

This sense of having lived on too late, of having survived the demolition of past dreams of the future, is what gives the ruin its specific frisson, and it still animates art and writing. But it's historically bound up with more pressing worries about the fate of one's own civilisation: nowhere more so than in the literary and artistic afterlife of a ruinous motif conjured by Rose Macaulay's grand-uncle Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1840. Reviewing Leopold von Ranke's History of the Popes in the Edinburgh Review, Macaulay speculates that in the distant future Catholicism "may still exist in undiminished vigour when some traveller from New Zealand shall, in the midst of a vast solitude, take his stand on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St Paul's". Macaulay's New Zealander, gazing at the wreckage of the metropolis (and by extension on the fall of the British empire), was for decades a popular image of London's future ruin – its most notable avatar is Gustave Doré's engraving The New Zealander.

Images of the modern city in ruins proliferated in the Victorian period – Richard Jefferies's 1885 novel After London is the best-known example, with its vision of a city reverting to nature following some unnamed calamity – but the following century had another perspective on the now venerable and even hackneyed trope of ruin: for modernism the city, even (or especially) as it pretended to progress or novelty, was already in ruins. The Waste Land is an obvious instance, with its fragmentary vision of the unreal city. But consider too the photographs of Eugène Atget, which capture a Paris being demolished and rebuilt at the same time, or Walter Benjamin's Arcades Project: a critical-historical phantasmagoria conjured from the already decaying Parisian shopping arcades of just a few decades earlier. In architectural terms, the most thoroughgoing visions of the city of the future were haunted too by ruination: Le Corbusier's projected Ville Radieuse depended on the wholesale ruin of the existing city, and the classical kitsch that Albert Speer planned for Hitler's future Germania was designed with its potential "ruin value" in mind.

The second world war tested the taste for ruins to its limits – such wholesale destruction was surely unsuited to melancholy thoughts of an aesthetic cast. Rose Macaulay worries at the problem in the "Note on New Ruins" that she appended to Pleasure of Ruins: the bomb sites of London, she fears, are still too jagged and raw in the memory to qualify as ruins. And yet many of the most affecting images of the depredations of total war and, especially, of the bombing of cities are clearly indebted to romantic precursors. Macaulay herself was not immune to their pleasures: in 1949 her novel The World My Wilderness hymned the Eliotic wasteland that London had become, her feral teenage protagonists running wild among gaping cellars and ruderal meadows. One thinks, too, of Cecil Beaton's blitz photographs, or Paul Nash's 1941 painting Totes Meer and its rhyming of wrecked aircraft with Friedrich's Sea of Ice. In the immediate postwar period, it was cinema that frankly embraced the visual allure and import of the ruin. In Germany, an entire genre of "ruin films" arose out of the devastation caused by Allied carpet-bombing, though the signature film in terms of capturing the plight of Berlin's orphaned Trümmerkinder, or children of the ruins, was by an Italian director: Roberto Rossellini's Germany Year Zero of 1948.

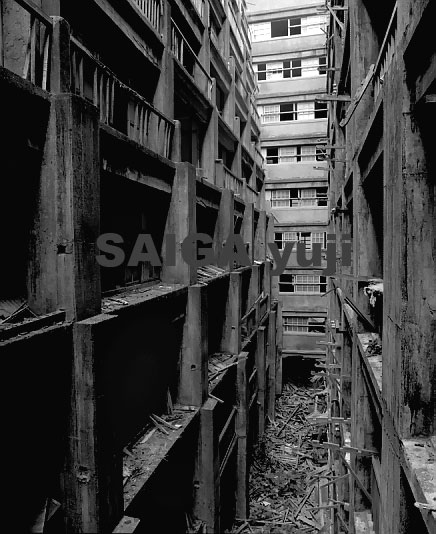

Postwar culture is littered with images of ruins past and potentially to come, the levelled cities of Europe becoming mixed up with photographs and footage of real or anticipated nuclear destruction, the whole apocalyptic imaginary hardly alleviated by a sense that urban reconstruction was in itself a form of ruin lust: cities rising into wreckage and the earth poisoned by new industries. Chris Marker's La Jetée (1962) begins with views of post-apocalyptic Paris that are clearly mocked-up from photographs of real cities in ruin in the 1940s; Michelangelo Antonioni's Red Desert (1964) shows the factory districts of Ravenna as a lurid, smoky hell that already looks post-industrial and decayed. And in the same decade JG Ballard began to formulate a view of ex-urban modernity — the concrete non-places of motorway flyovers and airport environs — as the landscape of a decidedly post-romantic sublime.

If Ballard is the English laureate of late-modern ruins, his influence still palpable in the writings of Iain Sinclair or the poetic dross-scape of Michael Symmons Roberts and Paul Farley's recent book Edgelands, the figure around whom the artistic fascination with ruins has crystallised in recent years is the artist Robert Smithson. In the years before his death in 1973 Smithson, who had certainly been reading Eliot and Ballard, combined ambitious land-art projects (his Spiral Jetty of 1970 is the best known) with a series of inventive and wry essays on the ruinous condition of the modern American landscape. Writing of his native New Jersey in 1967, in an essay titled "A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic", Smithson affected to have found, on the outskirts of a declining industrial town, the contemporary "eternal city": an agglomeration of half-built highways and rusting factory relics to rival the architectural and artistic treasures of ancient Rome. New Jersey, writes Smithson memorably, is "a utopia minus a bottom, a place where the machines are idle, and the sun has turned to glass".

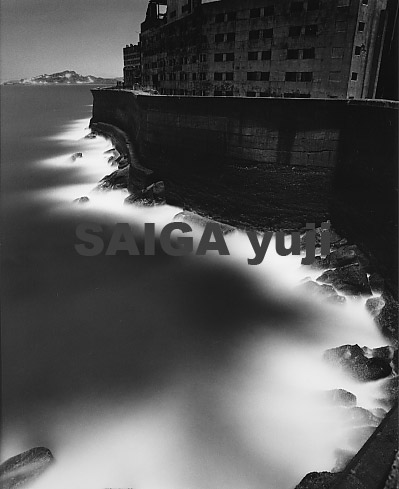

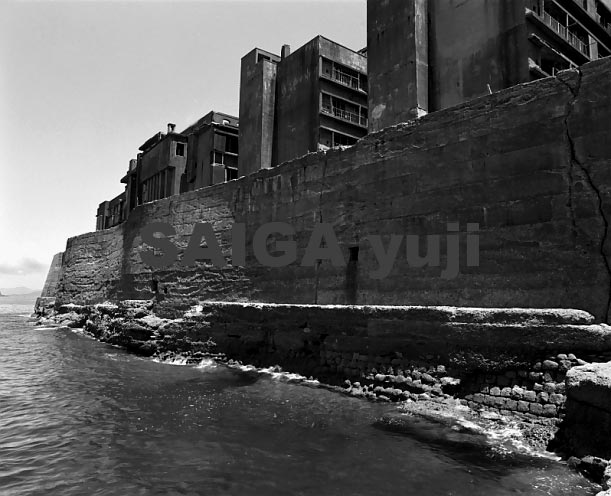

Smithson's influence – and especially his notion of "ruins in reverse", in which construction and dissolution cannot be told apart – is all over the ruinous turn that many artists and writers took in the last decade or so. Tacita Dean's films are a case in point, with their frequent focus on defunct technology or architecture. Jane and Louise Wilson followed Ballard and the French urban theorist Paul Virilio in exploring the derelict remains of the Nazis' Atlantic Wall fortifications. Younger artists such as Cyprien Gaillard and collaborators Karin Kihlberg and Reuben Henry have continued to explore the idea of modern ruins, while Owen Hatherley's 2011 book A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain essayed a critique of the ruinous effects of recent urban planning in the UK. (Later this year Hatherley's sequel, A New Kind of Bleak will show that process nearing its endgame, from Aberdeen to Plymouth, Croydon to Belfast.)

An obsession with ruins can risk a fall into mere sentiment or nostalgia: ruin lust was already a cliché in the 18th century, and its periodic revivals may put one in mind of Gilbert and Sullivan: "There's a fascination frantic / In a ruin that's romantic." The great interest in the remarkable images of decayed Detroit – in the photographs, for example, of Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, on show at the Wilmotte Gallery in London from this week – is easily understandable but seems oddly detached from analyses of the political forces that brought the city to its present sorry pass. It may be that as a cultural touchstone the idea of ruin needs to slump into the undergrowth again. But the history of ruin aesthetics tells us that it would likely resurface in time, charged again with artistic and political energy, and we'd find ourselves looking once more at blasted or burned cities with a visionary or melancholy eye, just as Rose Macaulay did in 1941, ambiguously lamenting a bombed-out house where "the stairway climbs up and up, undaunted, to the roofless summit where it meets the sky".

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/ ... -buildings