I can't seem to get away from The New Yorker, I let my subscription lapse but now my mom saves her issues for me...aaugh! I read them on the bus to work.

This article contains some interesting ideas and when they wander afield of mainstream the annoying New Yorker writer nudges us back toward the reservation. I hate that. Just shut up, would you? Sheesh.

It's about about Peter Thiel, the founder of PayPal, whizkid investor etc. and recent Bilderberg invitee (that last not mentioned in the article of course). What strikes me most is his apparent lack of any emotional expression. As to his thinking in business and politics, for all his outside-the-box vision kinda stuff, his primary aim seems to be a "world safe for capitalism." Overall he makes me slightly anxious.

Copy for educational purposes:

http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011 ... ntPage=all

No Death, No Taxes

The libertarian futurism of a Silicon Valley billionaire.

by George Packer

November 28, 2011

The credo of Thiel’s venture-capital firm: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” Photograph by Robert Maxwell.

Peter Thiel pulled an iPhone out of his jeans pocket and held it up. “I don’t consider this to be a technological breakthrough,” he said. “Compare this with the Apollo space program.” Thiel, an entrepreneur who runs both a hedge fund and a venture-capital firm, was waiting for a table at Café Venetia, which is on University Avenue in downtown Palo Alto, California. The street is the launchpad of Silicon Valley. All the café’s tables were occupied by healthy, downwardly dressed people using Apple devices while discussing idea creation and angel investments. Ten years ago, Thiel met his friend Elon Musk for coffee at the same spot, and decided that PayPal, the online-payments company they had helped found, should go public. Soon after the initial public offering, in 2002, PayPal was sold to eBay for one and a half billion dollars, and Thiel’s take was fifty-five million.

Most of Thiel’s fortune was made within shouting distance of Café Venetia. PayPal’s first office was five blocks down the street, above a bike shop. Just across the street was 156 University Avenue, the original headquarters of Facebook. In the summer of 2004, Thiel gave a Harvard dropout named Mark Zuckerberg a half-million-dollar loan, the first outside investment in Facebook, which Thiel later converted into a seven-per-cent ownership stake and a seat on the board; his share today is worth at least one and a half billion dollars. Facebook’s successor at 156 University Avenue is Palantir Technologies, whose software helps government agencies track down terrorists, fraudsters, and other criminals, by detecting subtle patterns in torrents of information. Thiel co-founded Palantir in 2004 and invested thirty million dollars in it. Palantir is now valued at two and a half billion dollars, and Thiel is the chairman of the board. He might be the most successful technology investor in the world.

The information age has made Thiel rich, but it has also been a disappointment to him. It hasn’t created enough jobs, and it hasn’t produced revolutionary improvements in manufacturing and productivity. The creation of virtual worlds turns out to be no substitute for advances in the physical world. “The Internet—I think it’s a net plus, but not a big one,” he said. “Apple is an innovative company, but I think it’s mostly a design innovator.” Twitter has a lot of users, but it doesn’t employ that many Americans: “Five hundred people will have job security for the next decade, but how much value does it create for the entire economy? It may not be enough to dramatically improve living standards in the U.S. over the next decade or two decades.” Facebook was, he said, “on balance positive,” because of the social disruptions it had created—it was radical enough to have been “outlawed in China.” That’s the most he will say for the celebrated era of social media.

Thiel rarely updates his Facebook page. He “never adapted to the BlackBerry/iPhone/e-mail thing,” and began texting only a year ago. He hasn’t quite mastered the voice-recognition system in his sports car. Though he owns a seven-million-dollar mansion in San Francisco’s Marina District, and bought a twenty-seven-million-dollar oceanfront property in Maui in July, he sees the staggering rise in Silicon Valley’s real-estate values as a sign not of progress but of “how people have found it very hard to keep up.” There was almost never a free table at Café Venetia, he noted, or anywhere else on University Avenue, throwing the sanity of local housing prices into further question. Silicon Valley exuberance had become yet another sign of blinkered élite thinking.

Thiel—who grew up middle class, earned degrees from Stanford and Stanford Law School, worked at a white-shoe New York law firm and a premier Wall Street investment bank, employs two assistants and a chef, and is currently reading obscure essays by the philosopher Leo Strauss—holds élites in contempt. “This is always a problem with élites, they’re always skewed in an optimistic direction,” he said. “It may be true to an even greater extent at present. If you were born in 1950, and you were in the top-tenth percentile economically, everything got better for twenty years automatically. Then, after the late sixties, you went to a good grad school, and you got a good job on Wall Street in the late seventies, and then you hit the boom. Your story has been one of incredible, unrelenting progress for sixty-one years. Most people who are sixty-one years old in the U.S.? Not their story at all.”

When Thiel questions the Internet’s significance, it’s not out of an indifference to technology. He’s enraptured with it. Indeed, his main lament is that America—the country that invented the modern assembly line, the skyscraper, the airplane, and the personal computer—has lost its belief in the future. Thiel thinks that Americans who are beguiled by mere gadgetry have forgotten how expansive technological change can be. He looks back to the fifties and sixties, the heyday of popularized science and technology in this country, as a time when visions of a radically different future were commonplace. A key book for Thiel is “The American Challenge,” by the French writer J. J. Servan-Schreiber, which was published in 1967 and became a global best-seller. Servan-Schreiber argued that the dynamic forces of technology and education in the U.S. were leaving the rest of the world behind, and foresaw, by 2000, a post-industrial utopia in America. Time and space would no longer be barriers to communication, income inequality would shrink, and computers would set people free: “There will be only four work days a week of seven hours per day. The year will be comprised of 39 work weeks and 13 weeks of vacation. . . . All this within a single generation.”

In the era of “The Jetsons” and “Star Trek,” many Americans believed that travel to outer space would soon become routine. Extreme ideas caught the public imagination: building underwater cities, reforesting deserts, advancing human life with robots, reëngineering San Francisco Bay into two giant freshwater lakes divided by dams topped with dozens of highway lanes. For science-minded kids, the fictional worlds of Asimov, Heinlein, and Clarke seemed more real than reality, and destined to replace it.

Thiel says that the decline of the future began with the oil shock of 1973 (“the last year of the fifties”), and that ever since then we have been mired in a “tech slowdown.” Today, the sci-fi novels of the sixties feel like artifacts from a distant age. “One way you can describe the collapse of the idea of the future is the collapse of science fiction,” Thiel said. “Now it’s either about technology that doesn’t work or about technology that’s used in bad ways. The anthology of the top twenty-five sci-fi stories in 1970 was, like, ‘Me and my friend the robot went for a walk on the moon,’ and in 2008 it was, like, ‘The galaxy is run by a fundamentalist Islamic confederacy, and there are people who are hunting planets and killing them for fun.’ ”

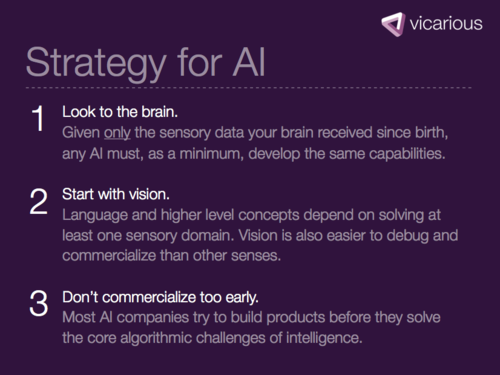

Thiel’s venture-capital firm, Founders Fund, has an online manifesto about the future that begins with a complaint: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” He believes that this failure of imagination explains many of the country’s problems—from the collapse in manufacturing to wage stagnation to the swelling of the financial sector. As he puts it, “You have dizzying change where there’s no progress.”

Thiel’s own story of progress began near the end of the golden age, in 1967, in Frankfurt, Germany. When Peter was one, his father, Klaus, moved the family to Cleveland. Klaus’s employment in various large engineering firms kept uprooting the family—South Africa and Namibia were other locations—and Peter attended seven elementary schools. The final one was near Foster City, a planned community, along the southern edge of San Francisco Bay, where the Thiels settled when he was in fifth grade. His parents banned TV until Peter was in junior high school. He grew up with the untrammelled self-confidence and competitiveness of a brilliant loner. He became a math prodigy and a nationally ranked chess player; his chess kit was decorated with a sticker carrying the motto “Born to Win.” (On the rare occasions when he lost in college, he swept the pieces off the board; he would say, “Show me a good loser and I’ll show you a loser.”) As a teen-ager, his favorite book was “The Lord of the Rings,” which he read again and again. Later came Solzhenitsyn and Rand. He acquired the libertarian faith in high school and took it close to the limit. (He now allows for government spending on science.)

Though Thiel is forty-four, it isn’t hard to imagine him in his late teens. He walks bent slightly forward at the waist, as if he found it awkward to have a body. He has reddish-brown hair with a trace of product on top, a long fleshy nose, clear blue eyes, and fantastically white teeth. He wears T-shirts and sneakers and prefers to hang out in coffee shops. He thought that the actor who played him, for thirty-four seconds, in “The Social Network” made him look too old, and too much like an investment banker. Although he’s acquired various luxuries that one associates with a twenty-first-century mogul, he lacks the firm taste that would allow him to spend money naturally. His most striking feature is his voice: something metallic seems to be caught in his throat, deepening and flattening the timbre into an authoritative drone. During intense moments of cerebration, he can get stuck on a thought and fall silent, or else stutter for a full forty seconds: “I would say it’s—it’s—um—you know, it is—yes, I sort of agree—I sort of—I sort of agree with all this. I don’t—um—I don’t—um—there is a sense in which it’s an unambitious perspective on politics.” Thiel expresses no ill will toward anyone, never stoops to gossip, and seldom cracks a joke or acknowledges that one has been made. In an amiably impersonal way, he is both transparent and opaque. He opens himself to all questions and answers them at length, but his line of reasoning is so uninflected that it becomes a barrier against intimacy.

Thiel’s closest friends date back to the early days of PayPal, in the late nineties, or even further, to his years at Stanford, in the late eighties. They are, for the most part, like him and one another: male, conservative, and super-smart in the fields of math and logical reasoning. These friendships were forged through abstract argument. David Sacks, who left PayPal in 2002 and now runs Yammer, a social-network site for businesses, met Thiel at Stanford, where they were members of the same eating club. The topics of conversation included evolutionary theory, libertarian philosophy, and the anthropic principle, which holds that observations about the universe depend on the existence of a consciousness that can observe. “He would demolish your arguments in five minutes,” Sacks said. “It was like playing chess. He was libertarian, but he would ask questions like ‘Should there even be a market for nuclear weapons?’ He would drill down and find the weakness in your argument. He does like to win.”

In the summer of 1998, Max Levchin, a twenty-three-year-old Ukrainian-born computer programmer, had just arrived in the Bay Area when he heard Thiel give a talk at Stanford on currency trading. The next day, they met for smoothies in Palo Alto and came up with the idea that became PayPal: a system of electronic payment designed to make e-commerce easy, consistent, and secure. “I’m addicted to hanging out with smart people,” Levchin said. “And I found myself craving more time with Peter.” While developing the first prototype for PayPal, Levchin and Thiel tried to stump each other with increasingly difficult math puzzles. (How many digits does the number 125100 have? Two hundred and ten.) “It was a bit like a weird courting process, nerds trying to impress each other,” Levchin said.

In 2005, Eliezer Yudkowsky, an artificial-intelligence researcher, met Thiel at a dinner given by the Foresight Institute, a nanotechnology think tank in Palo Alto. They argued about whether someone could have an anti-knack for playing the stock market—whether “reverse stupidity” could be a form of intelligence. Yudkowsky said, “I remember all my conversations with Peter as very pleasant, far-ranging experiences that I would be more tempted to analogize to a real-world I.Q. test than to anything else.”

Few people in Silicon Valley can match Thiel’s combination of business prowess and philosophical breadth. He pushed hard to build PayPal, against formidable obstacles, because he wanted to create an online currency that could circumvent government control. (Though the company succeeded as a business, it never achieved that libertarian goal—Thiel attributes the failure mainly to heightened concerns, after 9/11, that terrorists might exploit electronic currency systems.) At Stanford, he was heavily influenced by the French philosopher René Girard, whose theory of mimetic desire—of people learning to want the same thing—attempts to explain the origins of social conflict and violence. Thiel once said, “Thinking about how disturbingly herdlike people become in so many different contexts—mimetic theory forces you to think about that, which is knowledge that’s generally suppressed and hidden. As an investor-entrepreneur, I’ve always tried to be contrarian, to go against the crowd, to identify opportunities in places where people are not looking.”

Thiel’s friends value his openness to intellectual weirdness. Elon Musk, who went on from PayPal to found SpaceX, a company that makes low-cost rockets for space exploration, and Tesla, the electric-car manufacturer, said, “He’s unconstrained by convention. There are very few people in the world who actually use unconstrained critical thinking. Almost everyone either thinks by analogy or follows the crowd. Peter is much more willing to look at things from a first-principle standpoint.” Musk added, “I’m somewhat libertarian, but Peter’s extremely libertarian.”

Yet Thiel is hardly an unconstrained person. He seems uneasy with the world of grownup feelings, as if he were still a precocious youth. Someone who has known him for more than a decade said, “He’s very cerebral, and I’m not sure how much value he places on the more intimate human emotions. I’ve never seen him express them. It’s certainly not the most developed aspect of his personality.” The friend added, “There are some irreconcilable elements that remain unreconciled in him”—a reference to Thiel’s being both Christian and gay, two facts that get no mention in his public utterances and are barely acknowledged in his private conversations. Though he is known for his competitiveness, he has an equally pronounced aversion to conflict. As chief executive of PayPal, which counted its users with a “world domination index,” Thiel avoided the personal friction that comes with managing people by delegating those responsibilities. Similarly, he hired from a small pool of like-minded friends, because “figuring out how well people work together would have been really difficult.”

One of those friends was Reid Hoffman. As students at Stanford, Thiel and Hoffman had argued about the relative importance of individuals and society in the creation of property. Thiel liked to quote Margaret Thatcher: “There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women.” Hoffman, who was far to the left of Thiel, countered that property was a social construct. In 1997, Hoffman put his beliefs about the primacy of social interactions into practice by starting SocialNet, an online dating service that Thiel calls “the first of the social-networking companies.” The model failed—users adopted fictional identities, which wasn’t the way most people wanted to connect on the Web—and Hoffman joined the board of PayPal, becoming the company’s vice-president of external relations.

In 2002, after PayPal was sold to eBay, Thiel turned to investing. He set up a hedge fund called Clarium Capital Management, starting with ten million dollars, most of it his own money. In the summer of 2004, Hoffman, who had recently founded LinkedIn, and Sean Parker, the Silicon Valley enfant terrible, introduced Thiel to Mark Zuckerberg, who was looking for a major investor in Facebook, then a site for college students. Thiel concluded that Facebook would succeed where similar companies had failed. His investment was a kind of philosophical concession to his friend Hoffman. Thiel explained, “Even though I still ideologically believed that it’s unhealthy if society is totalitarian or dominates everything, if I had been libertarian in the most narrow, Ayn Rand-type way, I would have never invested in Facebook.”

Clarium became one of the meteors of the hedge-fund world. Thiel and his colleagues placed bets that reflected his contrarian nature: they bought Japanese government bonds when others were selling, concluded that oil supplies were running out and went long on energy, and saw a bubble growing in the U.S. housing market. By the summer of 2008, Clarium had assets of more than seven billion dollars, a seven-hundred-fold increase in six years. Thiel acquired a reputation as an investing genius. That year, he was interviewed by Reason, the libertarian magazine. “My optimistic take is that even though politics is moving very anti-libertarian, that itself is a symptom of the fact that the world’s becoming more libertarian,” he said. “Maybe it’s just a symptom of how good things are.” In September, 2008, Clarium moved most of its operations to Manhattan.

The financial markets collapsed later that month. The fund began to lose money, and contrarianism became Thiel’s enemy. Expecting coördinated international intervention to calm the global economy, he went long on the stock market for the rest of the year—and stocks plummeted. Then, in 2009, he shorted stocks, and they rose. Investors began redeeming their money. Some of them grumbled that Thiel had brilliant ideas but couldn’t time trades or manage risk. One of Clarium’s largest investors concluded that the fund was a kind of Thiel cult, staffed by young intellectuals who were in awe of their boss and imitated his politics, his chess playing, his aversion to TV and sports. Clarium continued to bleed. In mid-2010, Thiel closed the New York office and moved Clarium back to San Francisco. This year, Clarium’s assets are valued at just three hundred and fifty million dollars; two-thirds of it is Thiel’s money, representing the entirety of his liquid net wealth. “Clarium is now a de-facto family office for Peter,” a colleague said. “He’s an exceptionally competitive person. He was on the cusp of entering the pantheon of world-class, John Paulson-esque hedge-fund managers in the summer of 2008, and he just missed it.”

Thiel took the first great humbling of his career well. No chess pieces were thrown. But, as his personal fortune declined, Thiel developed his pessimistic theory of a tech slowdown. He began to believe that, without a new technology revolution, globalization’s discontents would lead to increased conflict and, perhaps, a worldwide conflagration.

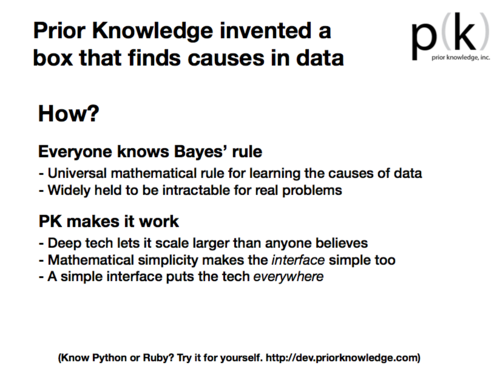

Thiel, who runs Founders Fund with Sean Parker and four others, poured his energy into a group of audacious projects that had less to do with financial returns than with utopian ideas. He invested in nanotechnology, space exploration, and robotics. Believing that computers with more brainpower than human beings would revolutionize life faster than any other technology, Thiel became the largest contributor to the Singularity Institute, a think tank, co-founded, in 2000, by his friend Eliezer Yudkowsky. The institute is preparing for the moment when a machine can make a smarter version of itself, and aims to insure that this “intelligence explosion” remains “human-friendly.” Thiel also gave three and a half million dollars to the Methuselah Foundation, whose goal is to reverse human aging. He became an early patron of the Seasteading Institute, a libertarian nonprofit group that was founded, in 2008, by Patri Friedman, a former Google engineer and Milton Friedman’s grandson. “Seasteading” refers to the founding of new city-states on floating platforms in international waters—communities beyond the reach of laws and regulations. The goal is to innovate more minimalist forms of government that would force existing regimes to change under competitive pressure. Thiel became an enthusiast of the idea, if not an actual candidate for resettlement on the high seas: he gave $1.25 million to Seasteading and, for a time, sat on its board.

The answer to the tech slowdown, Thiel concluded, was the lonely and audacious entrepreneur, seized with a burning vision and unafraid of the mindless herd. In 2009, Thiel posted an essay, “The Education of a Libertarian,” on the Cato Institute’s Web site. Sounding even more like an Ayn Rand hero than usual, he wrote, “In our time, the great task for libertarians is to find an escape from politics in all its forms—from the totalitarian and fundamentalist catastrophes to the unthinking demos that guides so-called ‘social democracy.’ . . . We are in a deadly race between politics and technology. . . . The fate of our world may depend on the effort of a single person who builds or propagates the machinery of freedom that makes the world safe for capitalism.” There was little doubt who the single person might be.

It was a rainy morning in Silicon Valley, and Thiel, in a windbreaker and jeans, was at the wheel of his dark-blue Mercedes SL500, trying to find an address in an industrial park between Highway 101 and the bay. The address was for a company called Halcyon Molecular, which wants to cure aging. Thiel, who is the company’s biggest investor and sits on its board, was driving with his seat belt off. “I oscillate on the seat-belt question,” he said.

I asked what the poles of the oscillation were.

“It’s uh—it’s the, uh—it’s the—it’s um—it’s probably, uh—it’s probably just that it’s not that—well, the pro-seat-belt argument is that it’s safer, and the anti-seat-belt argument is that if you know that it’s not as safe you’ll be a more careful driver.” He made a left turn and fastened his seat belt. “Empirically, it’s actually the safest if you wear a seat belt and are careful at the same time, so I’m not even going to try to debate this point.”

Thiel began telling the story of his first awareness of death. The memory seemed so fresh that it might as well have happened earlier that morning, but it took place when he was three years old, sitting on a cowhide rug in his parents’ apartment in Cleveland. He asked his father where the rug came from. A cow. What happened with the cow? It died. What did that mean? What was death? It was something that happened to all cows. All animals. All people. “And then it was sort of like—it was a very, very disturbing day,” Thiel said.

He never stopped being disturbed. Even in adulthood, he hasn’t made his peace with death, or what he calls “the ideology of the inevitability of the death of every individual.” For millions of people, Thiel believes, accepting mortality really means ignoring it—the complacency of the mob. He sees death as a problem to be solved, and the sooner the better. Given the current state of medical research, he expects to live to a hundred and twenty—a sorry compromise, given the grand possibilities of life extension.

In 2010, Luke Nosek, his friend and a partner at Founders Fund, told Thiel about a biotech startup that was developing a way to read the entire DNA sequence of the human genome through an electron microscope, potentially allowing doctors to learn everything about their patients’ genetic makeup quickly, for around a thousand dollars. Halcyon Molecular’s work held the promise of radical improvements in detecting and reversing genetic disorders, and Thiel decided to make Founders Fund the first outside investor. He took note of the talent and passion of the young scientists at Halcyon, and when they asked him for fifty thousand dollars he gave them a first round of five hundred thousand.

Thiel finally found Halcyon’s offices, parked, and hurried inside. In the hallway, a row of posters asked “WHAT IF WE HAD MORE TIME?” A picture of a futuristic library, a giant cage of bookshelves, was captioned “129,864,880 known books. How many have you read?” In the conference room, an all-hands meeting was going on: forty or so people, most of them in their twenties and thirties. They took turns giving slide presentations while Halcyon’s founder, William Andregg, asked the occasional question. Andregg, a lanky twenty-eight-year-old, was wearing cargo pants and a rumpled, untucked pink button-down shirt. One day, as an undergrad studying biochemistry at the University of Arizona, he made a list of all the things he wanted to do in life, which included travelling to other solar systems. He realized that he would not live long enough to do even a fraction of them. He plunged into gloom for a few weeks, then decided to put “cure aging” at the top of his list. At first, he was guarded about using the phrase, but Thiel urged him to make it the company’s message: some people might think it was crazy, but others would be attracted.

At the meeting, Thiel had no trouble following the technical jargon. During one particularly impenetrable presentation, he raised his hand. “I realize this is a dangerous question to ask, but what’s your over/under for prototype A?”

“Fifty per cent by the beginning of summer,” the scientist at the screen, laser pointer in hand, said. His hair and beard appeared to have been cut by a macaque. “Eighty per cent by the end of summer.”

“Very cool.”

When Thiel saw that I was lost, he scribbled on his yellow legal pad, “You attach big atoms (like platinum/gold) to DNA so it will show up under a microscope.”

As part of the weekly meeting, several staff members gave presentations about themselves. Michael Andregg, William’s brother and Halcyon’s chief technology officer, showed a slide that listed his hobbies and interests:

CRYONICS, IN CASE ALL ELSE FAILS

DODGEBALL

SELF-IMPROVEMENT

PERSONAL DIGITAL ARCHIVIZATION

SUPER INTELLIGENCE THROUGH A.I. OR UPLOADING

“Uploading,” I learned, means emulating a human brain on a computer.

On his way out, Thiel dispensed some business advice: by the following Monday, everyone in the company should have come up with the names of the three smartest people they knew. “We should try to build things through existing networks as much as possible,” he told the group. It was what he had done at PayPal. “We have to be building this company as if it’s going to be an incredibly successful company. Once you hit that inflection point, you’re under incredible pressure to hire people yesterday.”

The next stop, in another industrial park, a few miles away, was a company whose goal is to cure all viral diseases, by engineering “liquid computers”—systems of hundreds of molecules that can process basic information. If all goes according to plan, the liquid computers, introduced into cells, will recognize viral markers, causing cells with those markers to shut down by short-circuiting their operations. The company was at such an early stage that I was asked not to print the name. It consisted of three men and three women in their twenties, who were eating sandwiches and grapes in the kitchenette of a cramped office, above a lab that was packed with a DNA synthesizer, a flow cytometer, and other equipment. They were rebels from grad school—ideal finds for Thiel.

Last year, Brian, one of the two founders, was thirteen days away from defending his doctoral thesis in chemistry at the Scripps Research Institute, in La Jolla, when his adviser discovered that he was planning to leave academia and start a biotech company. “He got very upset and added a bunch of additional requirements to my graduation,” Brian said over lunch. “I had to quit and leave unfinished.” (Eventually, he completed his degree.) In Brian’s view, the best way to change the world was to start a company, “and just have everyone be properly motivated to get the goal done.” D.J., the other founder, was a refugee from Stanford. In his experience, even the best universities turned undergrads with Nobel-worthy ideas into conforming professionals.

In June, 2010, Brian and D.J. were camping out at a Motel 6 in Palo Alto and getting ready to drive to Pittsburgh, where they planned on starting the company at their alma mater, Carnegie Mellon. Before leaving, they spoke with Max Levchin, the programmer who was Thiel’s co-founder at PayPal. (Brian’s brother had interned for Levchin there.) Levchin introduced them to Thiel, who told them, “This isn’t a Pittsburgh company. This is a Silicon Valley company. Give me a week to convince you of that.” Brian and D.J. ended up starting their company in the Valley, with funding from Levchin and Thiel.

Thiel believes that education is the next bubble in the U.S. economy. He has compared university administrators to subprime-mortgage brokers, and called debt-saddled graduates the last indentured workers in the developed world, unable to free themselves even through bankruptcy. Nowhere is the blind complacency of the establishment more evident than in its bovine attitude toward academic degrees: as long as my child goes to the right schools, upward mobility will continue. A university education has become a very expensive insurance policy—proof, Thiel argues, that true innovation has stalled. In the midst of economic stagnation, education has become a status game, “purely positional and extremely decoupled” from the question of its benefit to the individual and society.

It’s easy to criticize higher education for burdening students with years of debt, which can force them into careers, like law and finance, that they otherwise might not have embraced. And a university degree has become an unquestioned prerequisite in an increasingly stratified society. But Thiel goes much further: he dislikes the whole idea of using college to find an intellectual focus. Majoring in the humanities strikes him as particularly unwise, since it so often leads to the default choice of law school. The academic sciences are nearly as dubious—timid and narrow, driven by turf battles rather than by the quest for breakthroughs. Above all, a college education teaches nothing about entrepreneurship. Thiel thinks that young people—especially the most talented ones—should establish a plan for their lives early, and he favors one plan in particular: starting a technology company.

Thiel thought about creating his own university, but he concluded that it would be too difficult to persuade parents to resist the prestige of the Ivies and Stanford. Then, last September, on a flight back from New York, he and Luke Nosek came up with the idea of giving fellowships to brilliant young people who would leave college and launch their own startups. Thiel moves fast: the next day, at TechCrunch Disrupt, an annual conference in San Francisco, he announced the Thiel Fellowships: twenty two-year grants, of a hundred thousand dollars each, to people under the age of twenty. The program made news, and critics accused Thiel of corrupting youth into chasing riches while truncating their educations. He pointed out that the winners could return to school at the end of the fellowship. This was true, but also somewhat disingenuous. No small part of his goal was to poke a stick in the eye of top universities and steal away some of their best.

Founders Fund, Clarium Capital Management, and Thiel’s foundation are housed together on the fourth floor of a stylish brick-and-glass building at the edge of San Francisco’s Presidio Park, with views of Alcatraz and the Golden Gate Bridge. The building is on the grounds of the San Francisco headquarters of Lucasfilm, and its first floor is decorated with statuary of Darth Vader and Yoda. As it happens, Thiel’s favorite movie was “Star Wars.”

After Thiel’s visits to the biotech startups, he was scheduled to interview the few of the fifty or so applicants, from a pool of six hundred, who had made the final cut for his fellowships. The first candidate to sit down at the dark-stained conference table was a Chinese-American, from Washington state, named Andrew Hsu. A nineteen-year-old prodigy, he still had braces on his teeth. At five, he had been solving simple algebra problems; at eleven, he and his brother co-founded a nonprofit group, the World Children’s Organization, that provided schoolbooks and vaccinations for Asian countries; at twelve, he entered the University of Washington; until recently, he had been a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience at Stanford, and he hoped to start a company that makes educational video games based on the latest neuroscientific research. “My core goal is to disrupt both the education and the game sectors,” he said, sounding like Peter Thiel.

Thiel expressed concern that the company would attract people with a nonprofit attitude, who felt that “it’s not about making money, we’re doing something good, so we don’t have to work as hard. And I think this has been an endemic problem, parenthetically, in the clean-tech space, which has attracted a lot of very talented people who believe they’re making the world a better place.”

“They don’t work as hard?” Hsu asked.

“Have you thought about how to mitigate against that problem?”

“So you’re saying that might be a problem just because the company has an educational slant?”

“Yes,” Thiel said. “Our main bias against investing in these sorts of companies is that you end up attracting people who just don’t want to work that hard. And that, sort of, is my deep theory on why they haven’t worked.”

Hsu caught Thiel’s drift. “Yeah, well, this is a game company. I wouldn’t call it an educational startup. I would say it’s a game startup. The types of people that I want to bring in are hard-core game engineers. So I don’t think these are the types of people that would slack off.”

Hsu would get a Thiel Fellowship. So would the Stanford sophomore from Minnesota, who had been obsessed with energy and water scarcity since the age of nine, when he tried to build the first-ever perpetual-motion machine. (He didn’t want to be named.) “After two years of being unsuccessful, I realized that even if we solved perpetual motion we wouldn’t use it if it was too expensive,” he told Thiel. “The sun is a source of perpetual energy, yet we’re not harnessing that. So I became obsessed with cost reductions.”

At seventeen, he had learned about photovoltaic heliostats, or solar trackers—“dual-access tracking mirrors that direct sunlight to one point.” If he could invent a cheap-enough way to produce heat using heliostats, solar energy could become financially competitive with coal. At Stanford, he started a company to work on the problem, but the university refused to count his hours on the project as academic units. So he went on leave and applied for a Thiel Fellowship.

I asked the candidate if he worried about losing the benefits of a university education. “I think I’m getting the best possible things out of Stanford,” he said. “I’m staying in this entrepreneurial house called Black Box. It’s about twelve minutes off campus. And so that’ll be really fun, because it’s really close to our office, and they have a hot tub and pool, and then just go to Stanford to see my friends on the weekends. You get all the best of the social but get to fundamentally work on what you love.”

A pair of Stanford freshmen—an entrepreneur named Stanley Tang and a programmer named Thomas Schmidt—came in next, with an idea for a mobile-phone application called QuadMob, which would allow you to locate your closest friends on a map, in real time. “It’s about taking your phone out and knowing where your friends are right now, whether they’re at the library or at the gym,” Tang, who came from Hong Kong, said. He had published a book called “eMillions: Behind-the-Scenes Stories of 14 Successful Internet Millionaires.” He went on, “On Friday night, every single week, I go to a party, and somehow you just lose your friends—people roll out to different parties. And I always have to text people, ‘Where are you, what are you doing, which party are you at?’ and I have to do that for, like, ten friends, and that’s just like a huge pain point.”

Tang was asked how QuadMob would change the world. “We’re redefining college life, we’re connecting people,” he said. “And, once this expands outside of college life, we’re really defining social life. We’d like to think of ourselves as bridging the gap between the digital and the physical world.”

Thiel was skeptical. It sounded like too many other venture startups looking to find a narrow opening between Facebook and Foursquare. It certainly wasn’t going to propel America out of the tech slowdown. The QuadMob candidates would not get a Thiel Fellowship.

In 1992, a Stanford law student named Keith Rabois tested the limits of free speech on campus by standing outside the dorm residence of an instructor and shouting, “Faggot! Faggot! Hope you die of AIDS!” The furious reaction to this provocation eventually drove Rabois out of Stanford. Thiel, who was in law school at the time, was also the president of the Stanford Federalist Society and the founder of the Stanford Review, a more highbrow, less bad-boy version of the notoriously incendiary Dartmouth Review. Not long after the incident, he decided to write a book with his friend David Sacks, exposing the dangers of political correctness and multiculturalism on campus. “Peter wanted to write a book pretty early on,” Sacks said. “If you had asked us in college, ‘Where do you think Peter’s going to end up?’ we would have said, ‘He’s going to be the next William F. Buckley or George Will.’ But we also knew he wanted to make money—not small sums, enormous sums. It’s sort of like if Buckley decided to become a billionaire first and then become an intellectual.”

“The Diversity Myth,” which appeared in 1995 (and remains Thiel’s only book), is more Dinesh D’Souza than “God and Man at Yale.” The authors line up example after example of the excesses of identity politics on campus, warning the country that a reign of intolerance, if not totalitarianism, is at hand. Characterizing the Rabois incident as a case of individual courage in the face of a witch hunt, they write, “His demonstration directly challenged one of the most fundamental taboos: To suggest a correlation between homosexual acts and AIDS implies that one of the multiculturalists’ favorite lifestyles is more prone to contracting the disease and that not all lifestyles are equally desirable.”

Thiel didn’t discuss with Sacks the personal implications of writing about the incident from a position hostile to homosexuality. “Peter wasn’t out of the closet back then,” Sacks told me. Thiel didn’t come out to his friends until 2003, when he was in his mid-thirties. “Do you know how many people in the financial world are openly gay?” he asked one friend, explaining that he didn’t want his sexual orientation to get in the way of his work.

Though the subject of homosexuality remains one that he doesn’t much like to discuss, Thiel says that he wishes he’d never written about the Rabois incident. “All of the identity-related things are in my mind much more nuanced,” he said. “I think there is a gay experience, I think there is a black experience, I think there is a woman’s experience that is meaningfully different. I also think there was a tendency to exaggerate it and turn it into an ideological category.” But his reaction against political correctness, he said, was just as narrowly ideological. “The Diversity Myth” now seems to cause Thiel mild embarrassment: political correctness on campus turned out to be the least of the country’s problems.

Thiel inherited the Christianity of his parents—he grew up as an Evangelical—but he describes his beliefs as “somewhat heterodox,” complicated by his cultural liberalism. “I believe Christianity is true,” he said. “I don’t sort of feel a compelling need to convince other people of that.” (It’s hard to think of another subject about which Thiel would say this.) Sonia Arrison, the author of “100 Plus,” a book on research into life extension, first met Thiel in 2003, when she heard him give a lunch talk about the failure of the U.S. Constitution. Eight years later, they are close friends, but she has no idea of his religious beliefs. “He won’t tell me what he is,” she said. “He thinks I should just know. He would never tell me whether he believes in God.”

Thiel compares the difference between faith and empiricism to the difference between technology and globalization: “Technology maps to miraculous supernatural creation, and globalization maps to naturalistic uniformitarian evolution. Technology involves the creation of radically new things that have not existed, and globalization maps to the continual copying of things that already exist.” As for being gay and Christian, Thiel said, “There obviously are all these things that are complicated about it, but I still don’t like the ideological thing that the correct response means that you have to give up your entire faith.”

Thiel’s friends say that these elements of his identity have no bearing on what matters most—his ideas. Thiel himself is not so categorical, but he fogs the subject up with elusiveness and irony: “I can come up with stories about how they’re factors, but I’m not sure they’re that interesting. The gay thing is that you’re sort of an outsider—there are things about it that are problematic, there are things about it that can be positive. But it also feels contrived. Maybe I’m more of an outsider because I was a gifted and introverted child,” not because he is gay. “Maybe it’s some complicated combination of all these things.” A knowing smile. “And maybe I’m not even an outsider.”

“Ideology” is one of Thiel’s least favorite words. Another is “politics.” Yet he has a long history of political involvement, beginning with the Stanford Review. After graduating from law school and clerking for a federal judge, he was turned down for a Supreme Court clerkship by Justices Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy. The fortune that Thiel has since accumulated has given him an influential role in Republican Party politics. During the primary phase of the 2008 Presidential campaign, he gave money to Ron Paul, the libertarian representative from Texas; during the general election, he gave money to John McCain. He has raised funds for Senator Jim DeMint, of South Carolina, and Representative Eric Cantor, of Virginia—both champions of the anti-government Tea Party.

In 2009, he gave a ten-thousand-dollar grant to a conservative libertarian organization that, in turn, funded James O’Keefe, a young activist. O’Keefe subsequently made undercover sting videos in which employees of the advocacy group Acorn appeared to offer advice on how to cover up tax evasion, human trafficking, and child prostitution. Thiel said that he didn’t know in advance about the videos—which have been widely denounced for being misleading—but, through a spokesman, he told the Village Voice that he had no objection to them, since he opposes things like human trafficking. Last year, at his Manhattan apartment in Union Square, Thiel hosted a fund-raiser for the gay conservative group GOProud, with Ann Coulter as the featured speaker. (Also last year, he appeared at a fund-raiser for gay marriage, and he has given money to the Committee to Protect Journalists.) Thiel regularly gets himself in trouble with his public provocations, such as this passage from his “Education of a Libertarian” essay:

The 1920s were the last decade in American history during which one could be genuinely optimistic about politics. Since 1920, the vast increase in welfare beneficiaries and the extension of the franchise to women—two constituencies that are notoriously tough for libertarians—have rendered the notion of “capitalist democracy” into an oxymoron.

Although Michele Bachmann once described homosexuality as “personal enslavement,” and Rick Perry compares it to alcoholism, Thiel says that the Republican Party of 2011 is actually more open and tolerant than the party of George W. Bush and Karl Rove. Gay marriage is no longer a wedge issue in Republican campaigns, Thiel believes, and, as for the outright hostility toward gays among some conservatives, “there are a lot of people who have crazy emotional issues, and politics is a way to channel that.” Nor is he much troubled by the Party’s distrust of science. Thiel himself, perhaps out of sheer contrarianism, is uncertain about Darwinian evolution. “I think it’s true,” he said, “but it’s also possible that it’s missing a lot of things, and it’s possible it’s not the most important thing.” Global warming is also “probably true,” but the matter is too clouded by political correctness to be properly assessed. The closer science gets to politics, the more vague and less convincing Thiel’s thinking becomes.

Despite, or perhaps because of, all this activism, Thiel has recently begun to express a strong antipathy toward politics. He doubts that it can solve fundamental problems, and he doesn’t think that libertarians can win elections, because most Americans would not vote for unfettered capitalism. “At its best, politics is pretty bad, and at its worst it’s really ugly,” he said. “So I think it would be good if we had a less political world. I think it was Disraeli who said that all merely political careers end in failure.” (Actually, it was the Conservative British politician Enoch Powell, who said, even more depressingly, “All political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure.”) Thiel hasn’t backed a candidate for 2012. He is spending his time and money building the “machinery of freedom” outside politics, so that technology will win the race.

In late March, Thiel hosted a small dinner party. His house stands grandly between the Presidio and the bay, beside the illuminated dome and arches of the Palace of Fine Arts. A chessboard and a bookcase filled with sci-fi and philosophy titles were the main indicators of who lived there; otherwise, the living and dining rooms were decorated, with impeccable elegance, for no one in particular. Thiel’s assistants—blondes in black dresses—refilled wineglasses and called the guests to dinner. A menu at each place setting announced a three-course meal, with a choice between poached wild salmon and pan-roasted sweet-pepper polenta.

Thiel’s guests seemed as out of place in this candlelit formality as their host. There was David Sacks, Thiel’s friend from Stanford and the co-author of “The Diversity Myth,” and Luke Nosek, the biotech specialist at Founders Fund, and Eliezer Yudkowsky, the artificial-intelligence researcher. Yudkowsky, an autodidact who never went past the eighth grade, is the author of a thousand-page online “fanfic” text called “Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality,” which recasts the original story in an attempt to explain Harry’s wizardry through the scientific method. Then there was Patri Friedman, the founder of the Seasteading Institute. An elfin man with cropped black hair and a thin line of beard, he was dressed in the eccentrically antic manner of Raskolnikov. He lived in Silicon Valley, in an “intentional community” as a free-love libertarian, about which he regularly blogged and tweeted: “Polyamory/competitive govt parallel: more choice/competition yields more challenge, change, growth. Whatever lasts is tougher.”

The two subjects of conversation were the superiority of entrepreneurship and the worthlessness of higher education. Nosek argued that the best entrepreneurs devoted their lives to a single idea. Founders Fund backed these visionaries and kept them in charge of their own companies, protecting them from the meddling of other venture capitalists, who were prone to replacing them with plodding executives.

Thiel picked up the theme. There were four places in America where ambitious young people traditionally went, he said: New York, Washington, Los Angeles, and Silicon Valley. The first three were used up; Wall Street lost its allure after the financial crisis. Only Silicon Valley still attracted young people with big dreams—though their ideas had sometimes already been snuffed out by higher education. The Thiel Fellowships would help ambitious young talents change the world before they could be numbed by the establishment.

I suggested that there was something to be gained from staying in school, reading great works of literature and philosophy, and arguing about ideas with people who have different views. After all, this had been the education of Peter Thiel. In “The Diversity Myth,” he and Sacks wrote, “The antidote to the multiculture is civilization.” I didn’t disagree. Wasn’t the world of libertarian entrepreneurs one more self-enclosed cell of identity politics?

Around the table, the response was swift and negative. Yudkowsky reported that he was having a “visceral reaction” to what I’d said about great books. Nosek was visibly upset: in high school, in Illinois, he had failed an English class because the teacher had said that he couldn’t write. If something like the Thiel Fellowships had existed, he and others like him could have been spared a lot of pain.

Thiel was smiling at the turn the conversation had taken. Then he pushed back his chair. “Most dinners go on too long or not long enough,” he said.

Escaping from politics is a libertarian’s right and a billionaire’s privilege. Thiel conceded, “There is always a question whether the escape from politics is somehow a selfish thing to do. You can say the whole Internet has something very escapist to it. You have all these Internet companies over the past decade, and the people who run them are sort of autistic. These mild cases of Asperger’s seem to be quite rampant. There’s no need for sales—the companies themselves are weirdly nonsocial in nature.” But, he added, “In a society where things are not great and a lot of stuff is fairly dysfunctional, that may actually be the thing where you can add the most value. You can say that’s an escapist impulse of sorts, or an anti-political impulse, but maybe it is also the best way you can actually help things in this country.”

Unlike many Silicon Valley boosters, Thiel knows that, as he puts it, thirty miles to the east most people are not doing well, and that this problem is more important than the next social-media company. He also knows that the establishment has been coasting for a long time and is out of answers. “The failure of the establishment points, maybe, to Marxism,” he said. “Maybe it points to libertarianism. It sort of suggests that we’ll get something outside the establishment, but it’s going to be this increasingly volatile trajectory of figuring out what that’s going to be.”

Thiel is never happier than when others scoff at his ventures, but he’s prone to the mistaken belief that the contrarian view is always right. He defended the indefensible after the Rabois incident, in part, because it was a case of one against all. His dislike of George W. Bush didn’t soften until his poll numbers hit rock bottom, and the same is now true for Barack Obama. During the financial crisis, Thiel lost billions of dollars because he refused to behave like the rest of the world. If artificial intelligence and seasteading are our only hope, it isn’t because politicians and professors mock and fear them. Nor is it at all clear how much hope Thiel’s utopian projects really offer.

The theory of an innovation gap as the main cause of economic decline has a lot of explanatory power, but it’s far from axiomatic. Trains and planes have scarcely improved since the seventies, and neither have median wages. What is the exact relation between the two? The middle class has eroded during the same years when the productivity of American workers has increased. (“I don’t believe the productivity numbers,” Thiel said flatly, defying reams of evidence. “We tend to just measure input, not output.”) Why, then, should breakthroughs in robotics and artificial intelligence reverse this trend? “Yes, a robotics revolution would basically have the effect of people losing their jobs, as you need fewer workers to do the same things,” Thiel said. “And it would have the benefit of freeing people up to do many other things. There would be social-dislocation problems, but I don’t think those are the ones we’ve been having. We’ve had a globalization problem.”

But, if the production of silicon chips can be outsourced, wouldn’t the same thing happen with anti-aging pills? And, in a deregulated market, what will guarantee an equitable distribution of those pills? Technological breakthroughs don’t always lessen inequality, and can sometimes increase it. Life extension is a vivid example: as Thiel said, “Probably the most extreme form of inequality is between people who are alive and people who are dead.” Most likely, the first people to live to a hundred and twenty will be rich.

No technological change would have more effect on the living standards of struggling Americans than improvements in energy and food, which dominate the economy and drive up prices. “That’s not one I focus on as much,” Thiel admitted. “It is very heavily politically linked, and my instinct is to stay away from that stuff.” Such oversights are telling. In Thiel’s techno-utopia, a few thousand Americans might own robot-driven cars and live to a hundred and fifty, while millions of others lose their jobs to computers that are far smarter than they are, then perish at sixty.

The next great technology revolution might be around the corner, but it won’t automatically improve most people’s lives. That will depend on politics, which is indeed ugly, but also inescapable. The libertarian worship of individual freedom, and contempt for social convention, comes easiest to people who have never really had to grow up. An appetite for disruption and risk—two of Thiel’s favorite words—reflects, in part, a sense of immunity to the normal heartbreak and defeats that a deadening job, money trouble, and unhappy children deal out to the “unthinking herd.” Thiel and his circle in Silicon Valley may be able to imagine a future that would never occur to other people precisely because they’ve refused to leave that stage of youthful wonder which life forces most human beings to outgrow. Everyone finds justification for his or her views in logic and analysis, but a personal philosophy often emerges from some archaic part of the mind, an early idea of how the world should be. Thiel is no different. He wants to live forever, have the option to escape to outer space or an oceanic city-state, and play chess against a robot that can discuss Tolkien, because these were the fantasies that filled his childhood imagination.

At least Thiel’s fantasies are aimed at improving the world. “It seems like we’ve not been thinking about the right issues for a long time,” he said. “I actually think it is a big step just to ask the question ‘What does one need to do to make the U.S. a better place?’ That’s where I’m weirdly hopeful, in spite of the fact that a lot of things aren’t going perfectly these days. There is a very cathartic crisis that’s gone on, and it’s not clear where it’s going to go. But at least everyone knows things are rotten. We’re in a much better place than when things were rotten and everyone thought things were great.” ♦