Fascism and the Future, Part One: Up From NewspeakOver the nearly eight years that I’ve been posting these weekly essays on the shape of the deindustrial future, I’ve found that certain questions come up as reliably as daffodils in April or airport food on a rough flight. Some of those fixate on topics I’ve discussed here recently, such as the vaporware du jour that’s allegedly certain to save industrial civilization and the cataclysm du jour that’s just as allegedly certain to annihilate it. Still, I’m glad to say that not all the recurring questions are as useless as these.

One of these latter deserves a good deal more attention than I’ve given it so far: whether the Long Descent of industrial society will be troubled by a revival of fascism. It’s a reasonable question to ask, since the fascist movements of the not so distant past were given their shot at power by the political failure and economic implosion of Europe after the First World War, and “political failure and economic implosion” is a tolerably good description of the current state of affairs in the United States and much of Europe these days. For that matter, movements uncomfortably close to the fascist parties of the 1920s and 1930s already exist in a number of European countries. Those who dismiss them as a political irrelevancy might want to take a closer look at history, for that same mistake was made quite regularly by politicians and pundits most of a century ago, too.

Nonetheless, with one exception—a critique some years back of talk in the peak oil scene about the so-called “feudal-fascist” society the rich were supposedly planning to ram down our throats—I’ve done my best to avoid the issue so far. This isn’t because it’s not important. It’s because the entire subject is so cluttered with doubletalk and distortions of historical fact that communication on the subject has become all but impossible. It’s going to take an entire post just to shovel away some of the manure that’s piled up in this Augean stable of our collective imagination, and even then I’m confident that many of the people who read this will manage to misunderstand every single word I say.

There’s a massive irony in that situation. When George Orwell wrote his tremendous satire on totalitarian politics, 1984, one of the core themes he explored was the debasement of language for political advantage. That habit found its lasting emblem in Orwell’s invented language Newspeak, which was deliberately designed to get in the way of clear thinking. Newspeak remains fictional—well, more or less—but the entire subject of fascism, and indeed the word itself, has gotten tangled up in a net of debased language and incoherent thinking as extreme as anything Orwell put in his novel.

These days, to be more precise, the word “fascism” mostly functions as what S.I. Hayakawa used to call a snarl word—a content-free verbal noise that expresses angry emotions and nothing else. One of my readers last week commented that for all practical purposes, the word “fascism” could be replaced in everyday use with “Oogyboogymanism,” and of course he’s quite correct; Aldous Huxley pointed out many years ago that already in his time, the word “fascism” meant no more than “something of which one ought to disapprove.” When activists on the leftward end of today’s political spectrum insist that the current US government is a fascist regime, they thus mean exactly what their equivalents on the rightward end of the same spectrum mean when they call the current US government a socialist regime: “I hate you.” It’s a fine example of the way that political discourse nowadays has largely collapsed into verbal noises linked to heated emotional states that drowns out any more useful form of communication.

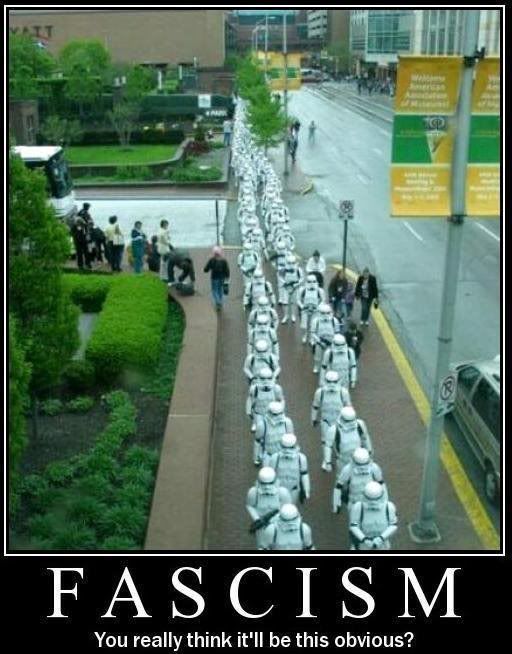

The debasement of our political language quite often goes to absurd lengths. Back in the 1990s, for example, when I lived in Seattle, somebody unknown to me went around spraypainting “(expletive) FACISM” on an assortment of walls in a couple of Seattle’s hip neighborhoods. My wife and I used to while away spare time at bus stops discussing just what “facism” might be. (Her theory was that it’s the prejudice that makes businessmen think that employees in front office jobs should be hired for their pretty faces rather than their job skills; mine, recalling the self-righteous declaration of a vegetarian cousin that she would never eat anything with a face, was that it’s the belief that the moral value of a living thing depends on whether it has a face humans recognize as such.) Beyond such amusements, though, lay a real question: what on earth did the graffitist think he was accomplishing by splashing that phrase around oh-so-liberal Seattle? Did he perhaps think that members of the American Fascist Party who happened to be goose-stepping through town would see the slogan and quail?

To get past such stupidities, it’s going to be necessary to take the time to rise up out of the swamp of Newspeak that surrounds the subject of fascism—to reconnect words with their meanings, and political movements with their historical contexts. Let’s start in the obvious place. What exactly does the word “fascism” mean, and how did it get from there to its current status as a snarl word?

That takes us back to southern Italy in 1893. In that year, a socialist movement among peasant farmers took to rioting and other extralegal actions to try to break the hold of the old feudal gentry on the economy of the region; the armed groups fielded by this movement were called fasci, which might best be translated “group” or “band.” Various other groups in the troubled Italian political scene borrowed the label thereafter, and it was also used for special units of shock troops in the First World War—Fasci di Combattimento, “combat groups,” were the exact equivalent of the Imperial German Army’s Sturmabteilungen, “storm troops.”

After the war, in 1919, an army veteran and former Socialist newspaperman named Benito Mussolini borrowed the label Fasci di Combattimento for his new political movement, about the same time that another veteran on the other side of the Alps was borrowing the term Sturmabteilung for his party’s brown-shirted bullies. The movement quickly morphed into a political party and adapted its name accordingly, becoming the Fascist Party, and the near-total paralysis of the Italian political system allowed Mussolini to seize power with the March on Rome in 1922. The secondhand ideology Mussolini’s aides cobbled together for their new regime accordingly became known as Fascism—“Groupism,” again, is a decent translation, and yes, it was about as coherent as that sounds. Later on, in an attempt to hijack the prestige of the Roman Empire, Mussolini identified Fascism with another meaning of the word fasci—the bundle of sticks around an axe that Roman lictors carried as an emblem of their authority—and that became the emblem of the Fascist Party in its latter years.

Of all the totalitarian regimes of 20th century Europe, it has to be said, Mussolini’s was far from the most bloodthirsty. The Fascist regime in Italy carried out maybe two thousand political executions in its entire lifespan; Hitler’s regime committed that many political killings, on average, every single day the Twelve-Year Reich was in power, and when it comes to political murder, Hitler was a piker compared to Josef Stalin or Mao Zedong. For that matter, political killings in some officially democratic regimes exceed Italian Fascism’s total quite handily. Why, then, is “fascist” the buzzword of choice to this day for anybody who wants to denounce a political system? More to the point, why do most Americans say “fascist,” mean “Nazi,” and then display the most invincible ignorance about both movements?

There’s a reason for that, and it comes out of the twists of radical politics in 1920s and 1930s Europe.

The founding of the Third International in Moscow in 1919 forced radical parties elsewhere in Europe to take sides for or against the Soviet regime. Those parties that joined the International were expected to obey Moscow’s orders without question, even when those orders clearly had much more to do with Russia’s expansionist foreign policy than they did with the glorious cause of proletarian revolution; at the same time, many idealists still thought the Soviet regime, for all its flaws, was the best hope for the future. The result in most countries was the emergence of competing Marxist parties, a Communist party obedient to Moscow and a Socialist party independent of it.

In the bare-knuckle propaganda brawl that followed, Mussolini’s regime was a godsend to Moscow. Since Mussolini was a former socialist who had abandoned Marx in the course of his rise to power, parties that belonged to the Third International came to use the label “fascist” for those parties that refused to join it; that was their way of claiming that the latter weren’t really socialist, and could be counted on to sell out the proletariat as Mussolini was accused of doing. Later on, when the Soviet Union ended up on the same side of the Second World War as its longtime enemies Britain and the United States, the habit of using “fascist” as an all-purpose term of abuse spread throughout the left in the latter two countries. From there, its current status as a universal snarl word was a very short step.

What made “fascist” so useful long after the collapse of Mussolini’s regime was the sheer emptiness of the word. Even in Italian, “Groupism” doesn’t mean much, and in other languages, it’s just a noise; this facilitated its evolution into an epithet that could be applied to anybody. The term “Nazi” had most of the same advantages: in most languages, it sounds nasty and doesn’t mean a thing, so it can be flung freely at any target without risk of embarrassment. The same can’t be said about the actual name of the German political movement headed by Adolf Hitler, which is one reason why next to nobody outside of specialist historical works ever mentions national socialism by its proper name.

That name isn’t simply a buzzword coined by Hitler’s flacks, by the way. The first national socialist party I’ve been able to trace was founded in 1898 in what’s now the Czech Republic, and the second was launched in France in 1903. National socialism was a recognized position in the political and economic controversies of early 20th century Europe. Fail to grasp that and it’s impossible to make any sense of why fascism appealed to so many people in the bitter years between the wars. To grasp that, though, it’s necessary to get out from under one of the enduring intellectual burdens of the Cold War.

After 1945, as the United States and the Soviet Union circled each other like rival dogs contending for the same bone, it was in the interest of both sides to prevent anyone from setting up a third option. Some of the nastier details of postwar politics unfolded from that shared interest, and so did certain lasting impacts on political and economic thought. Up to that point, political economy in the western world embraced many schools of thought. Afterwards, on both sides of the Iron Curtain, the existence of alternatives to representative-democracy-plus-capitalism, on the one hand, and bureaucratic state socialism on the other, became a taboo subject, and remains so in America to this day.

You can gain some sense of what was erased by learning a little bit about the politics in European countries between the wars, when the diversity of ideas was at its height. Then as now, most political parties existed to support the interests of specific social classes, but in those days nobody pretended otherwise. Conservative parties, for example, promoted the interests of the old aristocracy and rural landowners; they supported trade barriers, low property taxes, and an economy biased toward agriculture. Liberal parties furthered the interests of the bourgeoisie—that is, the urban industrial and managerial classes; they supported free trade, high property taxes, military spending, and colonial expansion, because those were the policies that increased bourgeios wealth and power.

The working classes had their choice of several political movements. There were syndicalist parties, which sought to give workers direct ownership of the firms for which they worked; depending on local taste, that might involve anything from stock ownership programs for employees to cooperatives and other worker-owned enterprises. Syndicalism was also called corporatism; “corporation” and its cognates in most European languages could refer to any organization with a government charter, including craft guilds and cooperatives. It was in that sense that Mussolini’s regime, which borrowed some syndicalist elements for its eclectic ideology, liked to refer to itself as a corporatist system. (Those radicals who insist that this meant fascism was a tool of big corporations in the modern sense are thus hopelessly misinformed—a point I’ll cover in much more detail next week.)

There were also socialist parties, which generally sought to place firms under government control; this might amount to anything from government regulation, through stock purchases giving the state a controlling interest in big firms, to outright expropriation and bureaucratic management. Standing apart from the socialist parties were communist parties, which (after 1919) spouted whatever Moscow’s party line happened to be that week; and there were a variety of other, smaller movements—distributism, social credit, and many more—all of which had their own followings and their own proposed answers to the political and economic problems of the day.

The tendency of most of these parties to further the interests of a single class became a matter of concern by the end of the 19th century, and one result was the emergence of parties that pursued, or claimed to pursue, policies of benefit to the entire nation. Many of them tacked the adjective “national” onto their moniker to indicate this shift in orientation. Thus national conservative parties argued that trade barriers and economic policies focused on the agricultural sector would benefit everyone; national liberal parties argued that free trade and colonial expansion was the best option for everyone; national syndicalist parties argued that giving workers a stake in the firms for which they worked would benefit everyone, and so on. There were no national communist parties, because Moscow’s party line didn’t allow it, but there were national bolshevist parties—in Europe between the wars, a bolshevist was someone who supported the Russian Revolution but insisted that Lenin and Stalin had betrayed it in order to impose a personal dictatorship—which argued that violent revolution against the existing order really was in everyone’s best interests.

National socialism was another position along the same lines. National socialist parties argued that business firms should be made subject to government regulation and coordination in order to keep them from acting against the interests of society as a whole, and that the working classes ought to receive a range of government benefits paid for by taxes on corporate income and the well-to-do. Those points were central to the program of the National Socialist German Workers Party from the time it got that name—it was founded as the German Workers Party, and got the rest of the moniker at the urging of a little man with a Charlie Chaplin mustache who became the party’s leader not long after its founding—and those were the policies that the same party enacted when it took power in Germany in 1933.

If those policies sound familiar, dear reader, they should. That’s the other reason why next to nobody outside of specialist historical works mentions national socialism by name: the Western nations that defeated national socialism in Germany promptly adopted its core economic policies, the main source of its mass appeal, to forestall any attempt to revive it in the postwar world. Strictly speaking, in terms of the meaning that the phrase had before the beginning of the Second World War, national socialism is one of the two standard political flavors of political economy nowadays. The other is liberalism, and it’s another irony of history that in the United States, the party that hates the word “liberal” is a picture-perfect example of a liberal party, as that term was understood back in the day.

Now of course when people think of the National Socialist German Workers Party nowadays, they don’t think of government regulation of industry and free vacations for factory workers, even though those were significant factors in German public life after 1933. They think of such other habits of Hitler’s regime as declaring war on most of the world, slaughtering political opponents en masse, and exterminating whole ethnic groups. Those are realities, and they need to be recalled. It’s crucial, though, to remember that when Germany’s National Socialists were out there canvassing for votes in the years before 1933, they weren’t marching proudly behind banners saying VOTE FOR HITLER SO FIFTY MILLION WILL DIE! When those same National Socialists trotted out their antisemitic rhetoric, for that matter, they weren’t saying anything the average German found offensive or even unusual; to borrow a highly useful German word, antisemitism in those days was salonfähig, “the kind of thing you can bring into the living room.” (To be fair, it was just as socially acceptable in England, the United States, and the rest of the western world at that same time.)

For that matter, when people talked about fascism in the 1920s and 1930s, unless they were doctrinaire Marxists, they didn’t use it as a snarl word. It was the official title of Italy’s ruling party, and a great many people—including people of good will—were impressed by some of the programs enacted by Mussolini’s regime, and hoped to see similar policies put in place in their own countries. Fascism was salonfähig in most industrial countries. It didn’t lose that status until the Second World War and the Cold War reshaped the political landscape of the western world—and when that happened, the complex reality of early 20th century authoritarian politics vanished behind a vast and distorted shadow that could be, and was, cast subsequently onto anything you care to name.

The downsides to this distortion aren’t limited to a failure of historical understanding. If a full-blown fascist movement of what was once the standard type were to appear in America today, it’s a safe bet that nobody except a few historians would recognize it for what it is. What’s more, it’s just as safe a bet that many of those people who think they oppose fascism—even, or especially, those who think they’ve achieved something by spraypainting “(expletive) FACISM” on a concrete wall—would be among the first to cheer on such a movement and fall in line behind its banners. How and why that could happen will be the subject of the next two posts.

Posted by John Michael Greer at 5:39 PM