Dancing the World into BeingThursday, 07 March 2013 09:53

By Naomi Klein, Yes! Magazine | Interview

Naomi Klein speaks with writer, spoken-word artist, and indigenous academic Leanne Betasamosake Simpson about “extractivism,” why it’s important to talk about memories of the land, and what’s next for Idle No More.

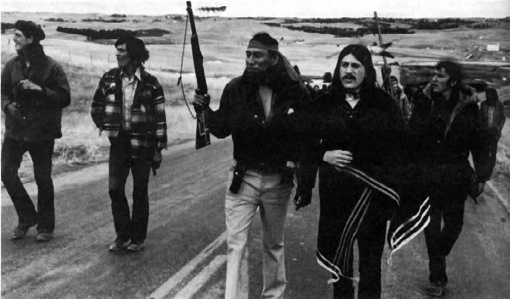

In December 2012, the Indigenous protests known as Idle No More exploded onto the Canadian political scene, with huge round dances taking place in shopping malls, busy intersections, and public spaces across North America, as well as solidarity actions as far away as New Zealand and Gaza. Though sparked by a series of legislative attacks on indigenous sovereignty and environmental protections by the Conservative government of Stephen Harper, the movement quickly became about much more: Canada’s ongoing colonial policies, a transformative vision of decolonization, and the possibilities for a genuine alliance between natives and non-natives, one capable of re-imagining nationhood. Throughout all this, Idle No More had no official leaders or spokespeople. But it did lift up the voices of a few artists and academics whose words and images spoke to the movement's deep aspirations. One of those voices belonged to Leanne Simpson, a multi-talented Mississauga Nishnaabeg writer of poetry, essays, spoken-word pieces, short stories, academic papers, and anthologies. Simpson's books, including Lighting the Eighth Fire: The Liberation, Protection and Resurgence of Indigenous Nations and Dancing on Our Turtle's Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence and a New Emergence, have influenced a new generation of native activists.

At the height of the protests, her essay, Aambe! Maajaadaa! (What #IdleNoMore Means to Me) spread like wildfire on social media and became one of the movement’s central texts. In it she writes: “I support #idlenomore because I believe that we have to stand up anytime our nation’s land base is threatened—whether it is legislation, deforestation, mining prospecting, condo development, pipelines, tar sands or golf courses. I stand up anytime our nation’s land base in threatened because everything we have of meaning comes from the land—our political systems, our intellectual systems, our health care, food security, language and our spiritual sustenance and our moral fortitude.”

On February 15, 2013, I sat down with Leanne Simpson in Toronto to talk about decolonization, ecocide, climate change, and how to turn an uprising into a “punctuated transformation.”

On Extractivism

Naomi Klein: Let’s start with what has brought so much indigenous resistance to a head in recent months. With the tar sands expansion, and all the pipelines, and the Harper government’s race to dig up huge tracts of the north, does it feel like we’re in some kind of final colonial pillage? Or is this more of a continuation of what Canada has always been about?

Leanne Simpson: Over the past 400 years, there has never been a time when indigenous peoples were not resisting colonialism. Idle No More is the latest—visible to the mainstream—resistance and it is part of an ongoing historical and contemporary push to protect our lands, our cultures, our nationhoods, and our languages. To me, it feels like there has been an intensification of colonial pillage, or that’s what the Harper government is preparing for—the hyper-extraction of natural resources on indigenous lands. But really, every single Canadian government has placed that kind of thinking at its core when it comes to indigenous peoples.

Indigenous peoples have lived through environmental collapse on local and regional levels since the beginning of colonialism—the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway, the extermination of the buffalo in Cree and Blackfoot territories and the extinction of salmon in Lake Ontario—these were unnecessary and devastating. At the same time, I know there are a lot of people within the indigenous community that are giving the economy, this system, 10 more years, 20 more years, that are saying “Yeah, we’re going to see the collapse of this in our lifetimes.”

Our elders have been warning us about this for generations now—they saw the unsustainability of settler society immediately. Societies based on conquest cannot be sustained, so yes, I do think we’re getting closer to that breaking point for sure. We’re running out of time. We’re losing the opportunity to turn this thing around. We don’t have time for this massive slow transformation into something that’s sustainable and alternative. I do feel like I’m getting pushed up against the wall. Maybe my ancestors felt that 200 years ago or 400 years ago. But I don’t think it matters. I think that the impetus to act and to change and to transform, for me, exists whether or not this is the end of the world. If a river is threatened, it’s the end of the world for those fish. It’s been the end of the world for somebody all along. And I think the sadness and the trauma of that is reason enough for me to act.

Naomi: Let’s talk about extraction because it strikes me that if there is one word that encapsulates the dominant economic vision, that is it. The Harper government sees its role as facilitating the extraction of natural wealth from the ground and into the market. They are not interested in added value. They’ve decimated the manufacturing sector because of the high dollar. They don’t care, because they look north and they see lots more pristine territory that they can rip up.

And of course that’s why they’re so frantic about both the environmental movement and First Nations rights because those are the barriers to their economic vision. But extraction isn’t just about mining and drilling, it’s a mindset—it’s an approach to nature, to ideas, to people. What does it mean to you?

Leanne: Extraction and assimilation go together. Colonialism and capitalism are based on extracting and assimilating. My land is seen as a resource. My relatives in the plant and animal worlds are seen as resources. My culture and knowledge is a resource. My body is a resource and my children are a resource because they are the potential to grow, maintain, and uphold the extraction-assimilation system. The act of extraction removes all of the relationships that give whatever is being extracted meaning. Extracting is taking. Actually, extracting is stealing—it is taking without consent, without thought, care or even knowledge of the impacts that extraction has on the other living things in that environment. That’s always been a part of colonialism and conquest. Colonialism has always extracted the indigenous—extraction of indigenous knowledge, indigenous women, indigenous peoples.

Naomi: Children from parents.

Leanne: Children from parents. Children from families. Children from the land. Children from our political system and our system of governance. Children—our most precious gift. In this kind of thinking, every part of our culture that is seemingly useful to the extractivist mindset gets extracted. The canoe, the kayak, any technology that we had that was useful was extracted and assimilated into the culture of the settlers without regard for the people and the knowledge that created it.

When there was a push to bring traditional knowledge into environmental thinking after Our Common Future, [a report issued by the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development] in the late 1980s, it was a very extractivist approach: “Let’s take whatever teachings you might have that would help us right out of your context, right away from your knowledge holders, right out of your language, and integrate them into this assimilatory mindset.” It’s the idea that traditional knowledge and indigenous peoples have some sort of secret of how to live on the land in an non-exploitive way that broader society needs to appropriate. But the extractivist mindset isn’t about having a conversation and having a dialogue and bringing in indigenous knowledge on the terms of indigenous peoples. It is very much about extracting whatever ideas scientists or environmentalists thought were good and assimilating it.

Naomi: Like I’ll just take the idea of “the seventh generation” and…

Leanne: …put it onto toilet paper and sell it to people. There’s an intellectual extraction, a cognitive extraction, as well as a physical one. The machine around promoting extractivism is huge in terms of TV, movies, and popular culture.

Naomi: If extractivism is a mindset, a way of looking at the world, what is the alternative?

Leanne: Responsibility. Because I think when people extract things, they’re taking and they’re running and they’re using it for just their own good. What’s missing is the responsibility. If you’re not developing relationships with the people, you’re not giving back, you’re not sticking around to see the impact of the extraction. You’re moving to someplace else.

The alternative is deep reciprocity. It’s respect, it’s relationship, it’s responsibility, and it’s local. If you’re forced to stay in your 50-mile radius, then you very much are going to experience the impacts of extractivist behavior. The only way you can shield yourself from that is when you get your food from around the world or from someplace else. So the more distance and the more globalization then the more shielded I am from the negative impacts of extractivist behavior.

On Idle No More

Naomi: With Idle No More, there was this moment in December and January where there was the beginning of an attempt to articulate an alternative agenda for the country that was rooted in a different relationship with nature. And I think of lot of people were drawn to it because it did seem to provide that possibility of a vision for the land that is not just digging holes and polluting rivers and laying pipelines.

But I think that may have been lost a little when we starting hearing some chiefs casting it all as a fight over resources sharing: “OK, Harper wants to extract $650 billion worth of resources, and how are we going to have a fair share of that?” That’s a fair question given the enormous poverty and the fact that these resources are on indigenous lands. But it’s not questioning the underlying imperative of tearing up the land for wealth.

Leanne: No, it’s not, and that is exactly what our traditional leaders, elders, and many grassroots people are saying as well. Part of the issue is about leadership. Indian Act chiefs and councils—while there are some very good people involved doing some good work—they are ultimately accountable to the Canadian government and not to our people. The Indian Act system is an imposed system—it is not our political system based on our values or ways of governing.

Indigenous communities, particularly in places where there is significant pressure to develop natural resources, face tremendous imposed economic poverty. Billions of dollars of natural resources have been extracted from their territories, without their permission and without compensation. That’s the reality. We have not had the right to say no to development, because ultimately those communities are not seen as people, they are seen as resources.

Rather than interacting with indigenous peoples through our treaties, successive federal governments chose to control us through the Indian Act, precisely so they can continue to build the Canadian economy on the exploitation of natural resources without regard for indigenous peoples or the environment. This is deliberate. This is also where the real fight will be, because these are the most pristine indigenous homelands. There are communities standing up and saying no to the idea of tearing up the land for wealth. What I think these communities want is our solidarity and a large network of mobilized people willing to stand with them when they say no.

These same communities are also continually shamed in the mainstream media and by state governments and by Canadian society for being poor. Shaming the victim is part of that extractivist thinking. We need to understand why these communities are economically poor in the first place—and they are poor so that Canadians can enjoy the standard of living they do. I say “economically poor” because while these communities have less material wealth, they are rich in other ways—they have their homelands, their languages, their cultures, and relationships with each other that make their communities strong and resilient.

I always get asked, “Why do your communities partner with these multinationals to exploit their land?” It is because it is presented as the only way out of crushing economic poverty. Industry and government are very invested in the “jobs versus the environment” discussion. These communities are under tremendous pressure from provincial governments, federal governments, and industry to partner in the destruction of natural resources. Industry and government have no problem with presenting large-scale environmental destruction by corporations as the only way out of poverty because it is in their best interest to do so.

There is a huge need to clearly articulate alternative visions of how to build healthy, sustainable, local indigenous economies that benefit indigenous communities and respect our fundamental philosophies and values. The hyper-exploitation of natural resources is not the only approach. The first step to that is to stop seeing indigenous peoples and our homelands as free resources to be used at will however colonial society sees fit.

If Canada is not interested in dismantling the system that forces poverty onto indigenous peoples, then I’m not sure Canadians, who directly benefit from indigenous poverty, get to judge the decisions indigenous peoples make, particularly when very few alternatives are present. Indigenous peoples do not have control over our homelands. We do not have the ability to say no to development on our homelands. At the same time, I think that partnering with large resource extraction industries for the destruction of our homelands does not bring about the kinds of changes and solutions our people are looking for, and putting people in the position of having to chose between feeding their kids and destroying their land is simply wrong.

Ultimately we’re not talking about a getting a bigger piece of the pie—as Winona LaDuke says—we’re talking about a different pie. People within the Idle No More movement who are talking about indigenous nationhood are talking about a massive transformation, a massive decolonization. A resurgence of indigenous political thought that is very, very much land-based and very, very much tied to that intimate and close relationship to the land, which to me means a revitalization of sustainable local indigenous economies that benefit local people. So I think there’s a pretty broad agreement around that, but there are a lot of different views around strategy because we have tremendous poverty in our communities.

On Promoting Life

Naomi: One of the reasons I wanted to speak with you is that in your writing and speaking, I feel like you are articulating a clear alternative. In a speech you gave recently at the University of Victoria, you said: “Our systems are designed to promote more life” and you talked about achieving this through “resisting, renewing, and regeneration”—all themes in Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back.

I want to explore the idea of life-promoting systems with you because it seems to me that they are the antithesis of the extractivist mindset, which is ultimately about exhausting and extinguishing life without renewing or replenishing.

Leanne: I first started to think about that probably 20 years ago, and it was through some of Winona LaDuke’s work and through working with elders out on the land that I started to really think about this. Winona took a concept that’s very fundamental to Anishinaabeg society, called mino bimaadiziwin. It often gets translated as “the good life,” but the deeper kind of cultural, conceptual meaning is something that she really brought into my mind, and she translated it as “continuous rebirth.” So, the purpose of life then is this continuous rebirth, it’s to promote more life. In Anishinaabeg society, our economic systems, our education systems, our systems of governance, and our political systems were designed with that basic tenet at their core.

I think that sort of fundamental teaching gives direction to individuals on how to interact with each other and family, how to interact with your children, how to interact with the land. And then as communities of people form, it gives direction on how those communities and how those nations should also interact. In terms of the economy, it meant a very, very localized economy where there was a tremendous amount of accountability and reciprocity. And so those kinds of things start with individuals and families and communities and then they sort of spiral outwards into how communities and how nations interact with each other.

I also think it’s about the fertility of ideas and it’s the fertility of alternatives. One of the things birds do in our creation stories is they plant seeds and they bring forth new ideas and they grow those ideas. Seeds are the encapsulation of wisdom and potential and the birds carry those seeds around the earth and grew this earth. And I think we all have that responsibility to find those seeds, to plant those seeds, to give birth to these new ideas. Because people think up an idea but then don’t articulate it, or don’t tell anybody about it, and don’t build a community around it, and don’t do it.

So in Anishinaabeg philosophy, if you have a dream, if you have a vision, you share that with your community, and then you have a responsibility for bringing that dream forth, or that vision forth into a reality. That’s the process of regeneration. That’s the process of bringing forth more life—getting the seed and planting and nurturing it. It can be a physical seed, it can be a child, or it can be an idea. But if you’re not continually engaged in that process then it doesn’t happen.

Naomi: What has the principle of regeneration meant in your own life?

Leanne: In my own life, I try to foster that with my own children and in my own family, because I have a lot of control over what happens in my own family and I don’t have a lot of control over what happens in the broader nation and broader society. But, enabling them, giving them opportunities to develop a meaningful relationship with our land, with the water, with the plants and animals. Giving them opportunities to develop meaningful relationships with elders and with people in our community so that they’re growing up in a very, very strong community with a number of different adults that they can go to when they have problems.

One of the stories I tell in my book is of working with an elder who’s passed on now, Robin Greene from Shoal Lake in Winnipeg, in an environmental education program with First Nations youth. And we were talking about sustainable development, and I was explaining that term from the Western perspective to the students. And I asked him if there was a similar concept in Anishinaabeg philosophy that would be the same as sustainable development. And he thought for a very long time. And he said no. And I was sort of shocked at the “no” because I was expecting there to be something similar. And he said the concept is backwards. You don’t develop as much as Mother Earth can handle. For us it’s the opposite. You think about how much you can give up to promote more life. Every decision that you make is based on: Do you really need to be doing that?

If I look at how my ancestors even 200 years ago, they didn’t spend a lot of time banking capital, they didn’t rely on material wealth for their well-being and economic stability. They put energy into meaningful and authentic relationships. So their food security and economic security was based on how good and how resilient their relationships were—their relationships with clans that lived nearby, with communities that lived nearby, so that in hard times they would rely on people, not the money they saved in the bank. I think that extended to how they found meaning in life. It was the quality of those relationships—not how much they had, not how much they consumed—that was the basis of their happiness. So I think that that’s very oppositional to colonial society and settler society and how we’re taught to live in that.

Naomi: One system takes things out of their relationships; the other continuously builds relationships.

Leanne: Right. Again, going back to my ancestors, they weren’t consumers. They were producers and they made everything. Everybody had to know how to make everything. Even if I look at my mom’s generation, which is not 200 years ago, she knew how to make and create the basic necessities that we needed. So even that generation, my grandmother’s generation, they knew how to make clothes, they knew how to make shelter, they knew how to make the same food that they would grow in their own gardens or harvest from the land in the summer through the winter to a much greater degree than my generation does. When you have really localized food systems and localized political systems, people have to be engaged in a higher level—not just consuming it, but producing it and making it. Then that self-sufficiency builds itself into the system.

My ancestors tended to look very far into the future in terms of planning, look at that seven generations forward. So I think they foresaw that there were going to be some big problems. I think through those original treaties and our diplomatic traditions, that’s really what they were trying to reconcile. They were trying to protect large tracts of land where indigenous peoples could continue their way of life and continue our own economies and continue our own political systems, I think with the hope that the settler society would sort of modify their way into something that was more parallel or more congruent to indigenous societies.

On Loving the Wounded

Naomi: You often start your public presentations by describing what your territory used to look like. And it strikes me that what you are saying is very different from traditional green environmental discourse, which usually focuses on imminent ecological collapse, the collapse that will happen if we don’t do X and Y. But you are basically saying that the collapse has already happened.

Leanne: I’m not sure focusing on imminent ecological collapse is motivating Canadians to change if you look at the spectrum of climate change denial across society. It is spawning a lot of apocalypse movies, but I think it is so overwhelming and traumatic to think about, that perhaps people shut down to cope. That’s why clearly articulated visions of alternatives are so important.

In my own work, I started to talk about what the land used to look like because very few people remember. Very early on, where I’m from, on the north shore of Lake Ontario, you saw the collapse of the salmon population in Lake Ontario by 1840. They used to migrate all the way up to Stony Lake—it was a huge deal for our nation. And then the eel population crashing with the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway and the Trent-Severn Waterway. So I think again, in a really local way, indigenous peoples have seen and lived through this environmental disaster where entire parts of their world collapsed really early on.

But it cycles, and the collapses are getting bigger and bigger and bigger. It’s getting to the point where I describe what my land used to look like because no one knows. No one remembers what southern Ontario looked like 200 years ago, which to me is really scary. How do we envision our way out of this when we don’t even remember what this natural environment is supposed to look like?

Naomi: I’ve spent the past two years living in British Columbia, where my family is, and I’ve been pretty involved in the fights against the tar sands pipelines. And of course the situation is so different there. There is still so much pristine wilderness, and people feel connected and protective of it. And I think for everyone, the fights against the pipelines have really been about falling more deeply in love with the land. It’s not an “anti” movement—it’s not about “I hate you.” It’s about “We love this place too much to let you desecrate it.” So it has a different feeling than any movement I’ve been a part of before. And of course the anti-pipeline movement on the West Coast is indigenous-led, and it’s also forged amazing coalitions of indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. I wonder how much those fights have contributed to the emergence of Idle No More—the fact of having these incredible coalitions and First Nations saying no to Harper, working together…

Leanne: But also because the Yinka Dene Alliance based their resistance on indigenous law. I remember feeling really proud when Yinka Dene Alliance did the train ride to the east. I was actually in Alberta at the time but we need to build on that because if you look in the financial sections of the papers for the last few years, there are these little indications that the pipelines are coming here too. And it’s becoming more so, with this refinery in Fredericton. So there needs to be a similar movement around pipelines as we’ve seen in British Columbia. But central Canada is behind.

Naomi: I think a lot of it has to do with the state the land is in. Because in B.C., that was the outrage over the Northern Gateway routing—“You want to build a pipeline through that part of B.C.? Are you nuts?” It was almost a gift to movement-building because they weren’t talking about building it through urban areas, they were talking about building it through some of the most pristine wilderness in the province. But we have such a harder job here, because there needs to be a process not just of protecting the land, but as you were saying, of finding the land in order to protect it. Whereas in B.C., it’s just so damn pretty.

Leanne: I think for me, it’s always been a struggle because I’ve always wanted to live in B.C. or the north, because the land is pristine. It’s easier emotionally for me. But I’ve chosen to live in my territory and I’ve chosen to be a witness of this. And I think that’s where, in the politics of indigenous women, and traditional indigenous politics, it is a politics based on love. That was the difference with Idle No More because there were so many women that were standing up. Because of colonialism, we were excluded for a long time from that Indian Act chief and council governing system. Women initially were not allowed to run for office, and it’s still a bastion of patriarchy. But that in some ways is a gift because all of our organizing around governance and politics and this continuous rebirth has been outside of that system and been based on that politics of love.

So when I think of the land as my mother or if I think of it as a familial relationship, I don’t hate my mother because she’s sick, or because she’s been abused. I don’t stop visiting her because she’s been in an abusive relationship and she has scars and bruises. If anything, you need to intensify that relationship because it’s a relationship of nurturing and caring. And so I think in my own territory I try to have that intimate relationship, that relationship of love—even though I can see the damage—to try to see that there is still beauty there. There’s still a lot of beauty in Lake Ontario. It’s one of those threatened lakes and it’s dying and no one wants to eat the fish. But there is a lot of beauty still in that lake. There is a lot of love still in that lake. And I think that Mother Earth as my first mother. Mothers have a tremendous amount of resilience. They have a tremendous amount of healing power. But I think this idea that you abandon it when something has been damaged is something we can’t afford to do in Southern Ontario.

Naomi: Exactly. But it’s such a different political project, right? Because the first stage is establishing that there’s something left to love. My husband talks about how growing up beside a lake you can’t swim in shapes your relationship with nature. You think nature is somewhere else. I think a lot of people don’t believe this part of the world is worth saving because they think it’s already destroyed, so you may as well abuse it some more. There aren’t enough people who are articulating what it means to build an authentic relationship with non-pristine nature. And it’s a different kind of environmental voice that can speak to the wounded, as opposed to just the perfect and pretty.

Leanne: If you can’t swim in it, canoe across it. Find a way to connect to it. When the lake is too ruined to swim or to eat from it, then that’s where the healing ceremonies come in, because you can still do ceremonies with it. In Peterborough, I wrote a spoken word piece around salmon in which I imagined myself as being the first salmon back into Lake Ontario and coming back to our territory. The lift-locks were gone. And I learned the route that the salmon would have gone in our language. And so that was one of the ways I was trying to connect my community back to that story and back to that river system, through this performance. People did get more interested in the salmon. The kids did get more interested because they were part of the dance work.

On Climate Change and Transformation

Naomi: In the book I’m currently writing I’m trying to understand why we are failing so spectacularly to deal with the climate crisis. And there are lots of reasons—ideological, material, and so on. But there are also powerful psychological and cultural reasons where we—and I’m talking in the “settler” we, I suppose—have been colonized by the logic of capitalism, and that has left us uniquely ill-equipped to deal with this particular crisis.

Leanne: In order to make these changes, in order to make this punctuated transformation, it means lower standards of living, for that 1 percent and for the middle class. At the end of the day, that’s what it means. And I think in the absence of having a meaningful life outside of capital and outside of material wealth, that’s really scary.

Naomi: Essentially, it’s saying: your life is going to end because consumerism is how we construct our identities in this culture. The role of consumption has changed in our lives just in the past 30 years. It’s so much more entwined in the creation of self. So when someone says, “To fight climate change you have to shop less,” it is heard as, “You have to be less.” The reaction is often one of pure panic.

On the other hand, if you have a rich community life, if your relationships feed you, if you have a meaningful relationship with the natural world, then I think contraction isn’t as terrifying. But if your life is almost exclusively consumption, which I think is what it is for a great many people in this culture, then we need to understand the depth of the threat this crisis represents. That’s why the transformation that we have to make is so profound—we have to relearn how to derive happiness and satisfaction from other things than shopping, or we’re all screwed.

Leanne: I see the transformation as: Your life isn’t going to be worse, it’s not going to be over. Your life is going to be better. The transition is going to be hard, but from my perspective, from our perspective, having a rich community life and deriving happiness out of authentic relationships with the land and people around you is wonderful. I think where Idle No More did pick up on it is with the round dances and with the expression of the joy. “Let’s make this fun.” It was women that brought that joy.

Naomi: Another barrier to really facing up to the climate crisis has to do with another one of your strong themes, which is the importance of having a relationship to the land. Because climate change is playing out on the land, and in order to see those early signs, you have to be in some kind of communication with it. Because the changes are subtle—until they’re not.

Leanne: I always take my kids to the sugar bush in March and we make maple syrup with them. And what’s happened over the last 20 years is every year our season is shorter. Last year was a near disaster because we had that week of summer weather in the middle of March. You need a very specific temperature range for making maple sugar. So it sort of dawned on me last year: I’m spending all of this time with my kids in the sugar bush and in 20 years, when it’s their term to run it, they’re going to have to move. Who knows? It’s not going to be in my territory anymore. That’s something that my generation, my family, is going to witness the death of. And that is tremendously sad and painful for us.

It’s things like the sugar bush that are the stories, the teachings, that’s really our system of governance, where children learn about that. It’s another piece of the puzzle that we’re trying to put back together that’s about to go missing. It’s happening at an incredibly fast rate, it’s changing. Indigenous peoples have always been able to adapt, and we’ve had a resilience. But the speed of this—our stories and our culture and our oral tradition doesn’t keep up, can’t keep up.

Naomi: One of the things that’s so difficult, when one immerses oneself in the climate science and comes to grips with just how little time we have left to turn things around, is that we know that real hard political work takes time. You can’t rush it. And a sense of urgency can even be dangerous, it can be used to say, “We don’t have time to deal with those complicated issues like colonialism and racism and inequality.” There is a history in the environmental movement of doing that, of using urgency to belittle all issues besides human survival. But on the other hand, we really are in this moment where small steps won’t do. We need a leap.

Leanne: This is one of the ways the environmental movement has to change. Colonial thought brought us climate change. We need a new approach because the environmental movement has been fighting climate change for more than two decades and we’re not seeing the change we need. I think groups like Defenders of the Land and the Indigenous Environmental Network hold a lot of answers for the mainstream environmental movement because they are talking about large-scale transformation. If we are not, as peoples of the earth, willing to counter colonialism, we have no hope of surviving climate change. Individual choices aren’t going to get us out of this mess. We need a systemic change. Manulani Aluli Meyer was just in Peterborough—she’s a Hawaiian scholar and activist—and she was talking about punctuated transformation. A punctuated transformation [means] we don’t have time to do the whole steps and time shift, it’s got to be much quicker than that.

That’s the hopefulness and inspiration for me that’s coming out of Idle No More. It was small groups of women around a kitchen table that got together and said, “We’re not going to sit here and plan this and analyze this, we’re going to do something.” And then three more women, and then two more women, and a whole bunch of people and then men got together and did it, and it wasn’t like there was a whole lot of planning and strategy and analyzing. It was people standing up and saying “Enough is enough, and I’m going to use my voice and I’m going to speak out and I’m going to see what happens.” And I think because it was still emergent and there were no single leaders and there was no institution or organization it became this very powerful thing.

On Next Steps

Naomi: What do you think the next phase will be?

Leanne: I think within the movement, we’re in the next phase. There’s a lot of teaching that’s happening right now in our community and with public teach-ins, there’s a lot of that internal work, a lot of educating and planning happening right now. There is a lot of internal nation-building work. It’s difficult to say where the movement will go because it is so beautifully diverse. I see perhaps a second phase that is going to be on the land. It’s going to be local and it’s going to be people standing up and opposing these large-scale industrial development projects that threaten our existence as indigenous peoples—in the Ring of Fire [region in Northern Ontario], tar sands, fracking, mining, deforestation… But where they might have done that through policy or through the Environmental Assessment Act or through legal means in the past, now it may be through direct action. Time will tell.

Naomi: I want to come back to what you said earlier about knowledge extraction. How do we balance the dangers of cultural appropriation with the fact that the dominant culture really does need to learn these lessons about reciprocity and interdependence? Some people say it’s a question of everybody finding their own inner indigenousness. Is that it, or is there a way of recognizing indigenous knowledge and leadership that avoids the hit-and-run approach?

Leanne: I think Idle No More is an example because I think there is an opportunity for the environmental movement, for social-justice groups, and for mainstream Canadians to stand with us. There was a segment of Canadian society, once they had the information, that was willing to stand with us. And that was helpful and inspiring to me as well. So I think it’s a shift in mindset from seeing indigenous people as a resource to extract to seeing us as intelligent, articulate, relevant, living, breathing peoples and nations. I think that requires individuals and communities and people to develop fair and meaningful and authentic relationships with us.

We have a lot of ideas about how to live gently within our territory in a way where we have separate jurisdictions and separate nations but over a shared territory. I think there’s a responsibility on the part of mainstream community and society to figure out a way of living more sustainably and extracting themselves from extractivist thinking. And taking on their own work and own responsibility to figure out how to live responsibly and be accountable to the next seven generations of people. To me, that’s a shift that Canadian society needs to take on, that’s their responsibility. Our responsibility is to continue to recover that knowledge, recover those practices, recover the stories and philosophies, and rebuild our nations from the inside out. If each group was doing their work in a responsible way then I think we wouldn’t be stuck in these boxes.

There are lots of opportunities for Canadians, especially in urban areas, to develop relationships with indigenous people. Now more than ever, there are opportunities for Canadians to learn. Just in the last 10 years, there’s been an explosion of indigenous writing. That’s why me coming into the city today is important, because these are the kinds of conversations where you see ways out of the box, where you get those little glimmers, those threads that you follow and you nurture, and the more you nurture them, the bigger they grow.

Naomi: Can you tell me a little bit about the name of your book, Dancing On Our Turtle’s Back, and what it means in this moment?

Leanne: I’ve heard Elder Edna Manitowabi tell one of our creation stories about a muskrat and a turtle for years now. In this story, there’s been some sort of environmental crisis. Because within Anishinaabeg cosmology, this isn’t the First World, maybe this is the Fourth World that we’re on. And whenever there’s an imbalance and the imbalance isn’t addressed, then over time there’s a crisis. This time, there was a big flood that covered the entire world. Nanabush, one of our sacred beings, ends up trapped on a log with many of the other animals. They are floating in this vast sea of water with no land in sight. To me, that feels like where we are right now. I’m on a very crowded log, the world my ancestors knew and lived in is gone, and me and my community need to come up with a solution even though we are all feeling overwhelmed and irritated. It’s an intense situation and no one knows what to do, no one knows how to make a new world.

So the animals end up taking turns diving down and searching for a pawful of dirt or earth to use to start to make a new world. The strong animals go first, and when they come up with nothing, the smaller animals take a turn. Finally, muskrat is successful and brings her pawfull of dirt up to the surface. Turtle volunteers to have the earth placed on her back. Nanibush prays and breaths life into that earth. All of the animals sing and dance on the turtle’s back in a circle, and as they do this, the turtle’s back grows. It grows and grows until it becomes the world we know. This is why Anishinaabeg call North America Mikinakong—the place of the turtle.

When Edna tells this story, she says that we’re all that muskrat, and that we all have that responsibility to get off the log and dive down no matter how hard it is and search around for that dirt. And that to me was profound and transformative, because we can’t wait for somebody else to come up with the idea. The whole point, the way we’re going to make this better, is by everybody engaging in their own being, in their own gifts, and embody this movement, embody this transformation.

And so that was a transformative story for me in my life and seemed to me very relevant in terms of climate change, in terms of indigenous resurgence, in terms of rebuilding the Anishinaabeg Nation. And so when people started round dancing all over the turtle’s back in December and January, it made me insanely happy. Watching the transformative nature of those acts, made me realize that it’s the embodiment, we have to embody the transformation.

Naomi: What did it feel like to you when it was happening?

Leanne: Love. On an emotional, a physical level, on a spiritual level. Yeah, it was love. It was an intimate, deep love. Like the love that I have for my children or the love that I have for the land. It was that kind of authentic, not romantic kind of fleeting love. It was a grounded love.

Naomi: And it can even be felt in a shopping mall.

Leanne: Even in a shopping mall. And how shocking is that?