SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 04, 2018

Reasons for becoming obsessed by the Banks Islands

I regularly bother my friends with my obsessions. I sent this e mail to Paul Janman recently.

Hi Paul,

let me just take up an aspect of our phone conversation and explain - as brusquely as possible, since you are busy and I am engulfed by kids - why I am fascinated by the Banks Islands.

For obvious reasons, we tend, in New Zealand, to contrast European and Polynesian culture. There was, after all, a confrontation between these cultures in the 19th century, a confrontation which has shaped our society, a confrontation that in many ways continues today. And, to be sure, there are real and significant differences between the cultures of Britain and other northern European countries on the one hand and Aotearoa and Tonga and Samoa and other Polynesian societies on the other: differences in the ownership of land, in attitudes toward history and the environment, in the balance of power between the individual and the collective, and so on.

But I think that if we turn our eyes to Melanesia (a region which I'll define here as extending from the northern half of Vanuatu through the Solomons, Bougainville and Papua New Guinea, sans their Polynesian outliers, and continuing into West Papua, Maluku and the eastern fringes of Timor-Leste), then we can get a new perspective on the European-Polynesian dichotomy. We can see that, despite all their differences, there are seminal similarities between the European and Polynesian civilisations.

Consider, for example, the extraordinary ability of both the Polynesian and the British to spread over vast areas of the world and plant and reproduce their culture there. Consider the homogenity of Polynesian civilisation, despite its vast reach: the fact that the language of Rapa Nui in the far east is so closely linked to that of Hawai'i in the far north, Aotearoa in the far south, and Nukuoro in the extreme west. Consider the gods and culture heroes - Maui, Tangaloa, and the rest - who have planted themselves on island after island. Consider the durability of the institution of hereditary chieftainship, in virtually every Polynesian possession. Consider the success of Polynesians in bringing their culture to the southern islands of Vanuatu, to Fiji, and to Kiribati in the last thousand years, despite the different cultures that the peoples of these places once practiced.

Patrick Vinton Kirch argues, of course, that the similarities between the various Polynesian societies can be explained by the fact that those societies had their origins in a single 'ancestral Polynesian culture', which was practiced by a discrete and very finite group of voyagers. And it is true that the Lapita ancestors of Polynesians only arrived in Tonga and Samoa and the other old parts of the civilisation three and a half thousand years ago. Polynesia doesn't, then, have the time depth of, say, Aboriginal Australian civilisation, or most Papuan societies.

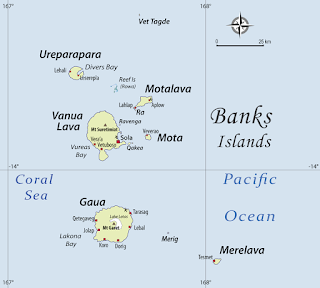

But let us consider for a moment the fact that the complicated series of archipelagos we call Vanuatu were only settled three and a half years ago by the same Lapita people who became Polynesians. Where the Polynesians established what is essentially the same culture across their vast domain, the ni-Vanuatu speak, even today, one hundred and thirty mutually incomprehensible languages, and maintain at least as many cultures. In the Banks Islands, in the far north of Vanuatu, this diversity is at its most extreme: ten thousand people speak seventeen languages. In the 19th century they spoke at least thirty-five tongues.

The Lapita culture seems to have been relatively hierarchical, and to have been administered, like its Polynesian descendants, by hereditary chiefs. But in the Banks Islands and in other parts of northern Vanuatu, hereditary chiefs are hard to find, and societies often tend to be acephalous, headless. The hereditary chiefs who dominate southern Vanuatu are the result of Polynesian influence over the last thousand years.

Why have the descendants of the same monolithic Lapita culture developed in such different ways in northern Vanuatu and in Polynesia? What can explain the incredible diversity of the Banks Islands? The linguist Alexandre Francois, who has spent his career documenting the languages of the Banks, argues that there exists in the group a 'powerful social bias towards differentiation and egalitarianism'.

None of the teeming societies of the Banks has been able or willing to impose itself on another; the average islander has been obliged to speak half a dozen tongues. The linguistic and cultural innovations - idiosyncratic pronunciations of words, neologisms, iconoclasms in dance and design - that might be suppressed in other societies are praised in the Banks.

Let's talk about this later!

S

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.com/2018 ... banks.html