Manafort’s man in KievThe Trump campaign chairman’s closeness to a Russian Army-trained linguist turned Ukrainian political operative is raising questions, concerns.

Jack Shafer08/18/2016 09:27 PM EDT

In an effort to collect previously undisclosed millions of dollars he’s owed by an oligarch-backed Ukrainian political party, Donald Trump’s campaign chairman Paul Manafort has been relying on a trusted protégé whose links to Russia and its Ukrainian allies have prompted concerns among Manafort associates, according to people who worked with both men.

The protégé, Konstantin Kilimnik, has had conversations with fellow operatives in Kiev about collecting unpaid fees owed to Manafort’s company by a Russia-friendly political party called Opposition Bloc, according to operatives who work in Ukraine.

A Russian Army-trained linguist who has told a previous employer of a background with Russian intelligence, Kilimnik started working for Manafort in 2005 when Manafort was representing Ukrainian oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, a gig that morphed into a long-term contract with Viktor Yanukovych, the Kremlin-aligned hard-liner who became president of Ukraine.

Kilimnik eventually became “Manafort’s Manafort” in Kiev, and he continued to lead Manafort’s office there after Yanukovych fled the country for Russia in 2014, according to Ukrainian business records and interviews with several political operatives who have worked in Ukraine’s capital. Kilimnik and Manafort then teamed up to help promote Opposition Bloc, which rose from the ashes of Yanukovych’s regime. The party is funded by oligarchs who previously backed Yanukovych, including at least one who the Ukrainian operatives say is close to both Kilimnik and Manafort.

Kilimnik has continued advising Opposition Bloc, which opposes Ukraine’s teetering pro-Western government, even as the party stopped fully paying Manafort’s firm, leaving it unable to pay some of its employees and rent, according to people familiar with the firm and its relationship to Opposition Bloc.

All the while, Kilimnik has told people that he remains in touch with his old mentor. He told several people that he traveled to the United States and met with Manafort this spring. The trip and alleged meeting came at a time when Manafort was immersed in helping guide Trump’s campaign through the bitter Republican presidential primaries, and was trying to distance himself from his work in Ukraine.

Russia and its relationship with Ukraine have emerged as a major issue in the race as have Manafort’s connections in the region. Allies of Trump’s Democratic rival Hillary Clinton have sought to use Trump’s stances on, and ties to, Russia to cast him as the preferred candidate of one of the U.S.’ top geopolitical foes.

That criticism intensified last month after a series of events. First, Trump’s campaign gutted a proposed amendment to the Republican Party platform that called for the U.S. to provide “lethal defensive weapons” for Ukraine to defend itself against Russian incursion, backers of the measure charged. The move defied a strong GOP consensus on the issue. Then, the U.S. government blamed Russia for a politically damaging hack of the Democratic National Committee, and finally Trump called for Russia to hack Clinton’s emails, though he later said he was “being sarcastic.”

Joking aside, Trump has demonstrated more interest in Russia’s affairs than in perhaps any other area of foreign policy. And his laissez faire approach toward Russia’s confrontational relations with its neighbors, combined with his open admiration of its authoritarian President Vladimir Putin and his employment of Manafort, have led experts from across the political spectrum to predict that a Trump presidency would augur to the Kremlin’s benefit.

With Trump receiving his first classified security briefings, and concerns about him spiking in the intelligence community, talk of Kilimnik’s connections to Russian intelligence — combined with his affiliation with the Russia-allied Opposition Bloc — could become a liability for Trump, predict associates of Manafort and Kilimnik.

That’s quite a turnabout from Manafort’s work in Ukraine, where Kilimnik’s Russian military background was seen as an advantage in working for the pro-Russian Yanukovych.

“There was a time that that didn’t bother us because our interests converged, but then at the end when Yanukovych was going down the wrong path, our interests diverged, and for whatever reasons, Paul kept him on,” one operative close to Manafort said of Kilimnik.

**

Kilimnik, a short man who goes by “Kostya” or sometimes “KK,” was born in the sprawling industrial city of Kriviy Rikh, Ukraine, in 1970, back when Ukraine was still a part of the Soviet Union.

Kilimnik attended a Soviet military school where he learned to speak fluent Swedish and English, which complemented the Russian and Ukrainian he already spoke. He joined the Russian Army as a translator, work that closely aligned him with the army’s intelligence services — an account pieced together from a handful of people who worked with him or were briefed on his background, including a former senior CIA official with direct knowledge of Kilimnik’s activities.

But the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, when Kilimnik was only 21, and it’s unclear whether he spent much time in active service. After the dissolution of the Communist-controlled country, Kilimnik bounced around a bit, doing freelance translating, until eventually landing a job in 1995 in the Moscow office of the International Republican Institute. The nonprofit group, which has branches around the world, works with political parties and candidates to bolster the democratic process — a mission viewed with suspicion in post-Communist Russia.

Kilimnik did not hide his military past from his new employer. In fact, when he was asked how he learned to speak such fluent English, he responded “Russian military intelligence,” according to one IRI official, who quipped, “I never called [the Russian military intelligence agency] GRU headquarters for a reference.”

It soon became an article of faith in IRI circles that Kilimnik had been in the intelligence service, according to five people who worked in and around the group in Moscow, who said Kilimnik never sought to correct that impression.

“It was like ‘Kostya, the guy from the GRU’ — that’s how we talked about him,” said a political operative who worked in Moscow at the time. “The institute was informed that he was GRU, but it didn’t matter at the time because they weren’t doing anything sensitive.”

IRI spokeswoman Julia Sibley confirmed that Kilimnik worked at IRI but wouldn’t comment on his background, explaining “Mr. Kilimnik hasn’t worked with IRI in over a decade and has no affiliation with us.”

Kilimnik — presented with a series of questions about his background, his relationship with Manafort and his current work — declined to comment.

People who worked with Kilimnik at IRI and in subsequent jobs describe him as an easygoing person and a brilliant linguist who was not prone to braggadocio, at least early in his career. They also say he was largely non-ideological or, if he was driven by any particular ideology, it was not easily detectable. For instance, they say he didn’t come across as opposed to the democratization of Russia, but nor did he appear to be an ardent reformer.

“He took the job at IRI for the money, not because he believed in the mission,” said another former IRI official. “When there was better more lucrative employment, he took that.”

In fact, Kilimnik, while still employed by IRI, did accept a second, higher-paying job translating and interpreting for a Manafort team that was working for the pro-Russian Ukrainian oligarch — and leading Yanukovych backer — Akhmetov in early 2005, according to four people who worked in or around IRI at the time.

Kilimnik “was always smart enough to get close to the money, and there was good money working for Akhmetov,” said a fellow Russian who was a longtime acquaintance.

At the time, Akhmetov was assembling a team of consultants to burnish the reputation of his business. It was facing regulatory action from a new government that had taken over when Yanukovych, who had been prime minister, lost his hold on power after his party tried to rig an October 2004 election to make him president.

Kilimnik was recruited to join Manafort’s team by a former IRI official named Philip M. Griffin, who had worked with Kilimnik at the institute. When IRI officials found out, they asked Kilimnik to resign for violating the nonprofit’s moonlighting prohibition. Several people around IRI say they suspected the institute regarded Kilimnik as too closely allied with Russia — even before he went to work for Akhmetov.

Whatever the reason, IRI employees were warned not to associate with Kilimnik after his resignation in April 2005, even though he continued to travel in the same circles as the group’s officials, according to one former IRI employee.

“I was advised that this is not a person that I want to be having a conversation with — that he could not be trusted,” the former employee said.

By the time Kilimnik left IRI, he had a wife and two children living in a modest house near Moscow’s Sheremetyevo International Airport.

He started spending more time in Kiev and apart from his family, and he eventually started adopting a flashier lifestyle. He hung out with the political movers and shakers in the city’s Hyatt hotel and was ferried around town by a chauffeur in European luxury sedans. He started wearing expensive suits and began living in a lavish mansion with a pool.

The lifestyle was sort of a JV version of the jet-setting existence of his boss, Manafort. Kilimnik and Manafort would work closely together over the next decade, traveling together and developing a bond that associates say continues to this day.

**

Manafort, now 67, made his name helping Republican presidents Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan in the 1970s and 1980s. But he spent most of the past three decades carving out a lucrative niche as a globe-trotting consultant to deep-pocketed foreign politicians and businessmen often looking to buff away stains on their reputations from allegations of corruption, plundering or human rights abuses. Among the boldfaced names in his client portfolio were Angolan guerilla army leader Jonas Savimbi, and former presidents Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines and Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire.

But those jobs would pale — both in terms of financial reward and degree of difficulty — to the gig to which Akhmetov referred Manafort and his team: returning Yanukovych to power.

A former trucking official who had been convicted and incarcerated as a teenager for serious crimes, Yanukovych had become a popular symbol of the corruption that plagues Ukraine after his team tried to rig the 2004 presidential election. A series of protests, which became known as the Orange Revolution, forced a re-vote, which Yanukovych lost.

While Manafort initially protested that Yanukovych was too deeply flawed to revive, Akhmetov eventually prevailed upon his American consultant to help Yanukovych and his political party, the Party of Regions, try to make a comeback in the 2006 parliamentary elections.

Manafort and his team, including Kilimnik, set about to recast Yanukovych as an inspiring leader who could work with the West. Under Manafort’s guidance, Yanukovych began studying English, and communicated in Ukrainian with the pro-European western part of the country, while using Russian to push pro-Russian themes in the east, which is linguistically, culturally and religiously aligned with Russia.

Manafort also implemented polling, micro-targeting and get-out-the-vote strategies that are de rigueur in American politics, but which Yanukovych had not previously used. Manafort even coached Yanukovych on his appearance, reportedly urging him to start blow-drying his hair, though one Manafort associate called the blow-drying claim a myth that was “total bullshit.”

Remarking on the transformation, a U.S. diplomat, in a hacked cable posted on WikiLeaks, wrote that the “Party of Regions is working to change its image from that of a haven for mobsters into that of a legitimate political party. Tapping the deep pockets of [Akhmetov], Regions has hired veteran K Street political help for its ‘extreme makeover’ effort … [Manafort’s firm] is among the political consultants that have been hired to do the nipping and tucking.”

Kilimnik was key to this effort, according to several people who worked with the team.

“The language was so important because you wanted to capture the nuances,” said one operative who worked with Manafort for the Party of Regions. “And because Paul doesn’t speak Russian or Ukrainian, he always had to have someone like that with him in meetings, so KK was with him all the time. He was very close to Paul and very trusted.”

The Party of Regions won the most seats in the 2006 parliamentary elections, and again in 2007 elections, paving the way for Yanukovych’s re-ascension as prime minister.

Manafort’s team began parlaying their connections into business ventures in the region, with Manafort and Rick Gates, who is now Manafort’s right-hand man on the Trump campaign, in late 2006 creating a private-equity fund in the Cayman Islands. The fund, called Pericles, used millions of dollars contributed by the Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska to purchase a Ukrainian cable and internet company.

But the venture soon collapsed. And, in a Cayman Islands legal filing to recoup Deripaska’s cash, lawyers named Kilimnik as one of seven “key individuals” involved in the partnership along with Manafort, Gates, and a handful of then-associates. Gates declined to comment.

A lawyer involved in the effort to recoup the investment didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Manafort entered into other ventures with other oligarchs, as well. And the operative who worked with Manafort’s team said, “These guys had a lot of stuff going on outside the campaign context, and KK was involved in all of that as well.”

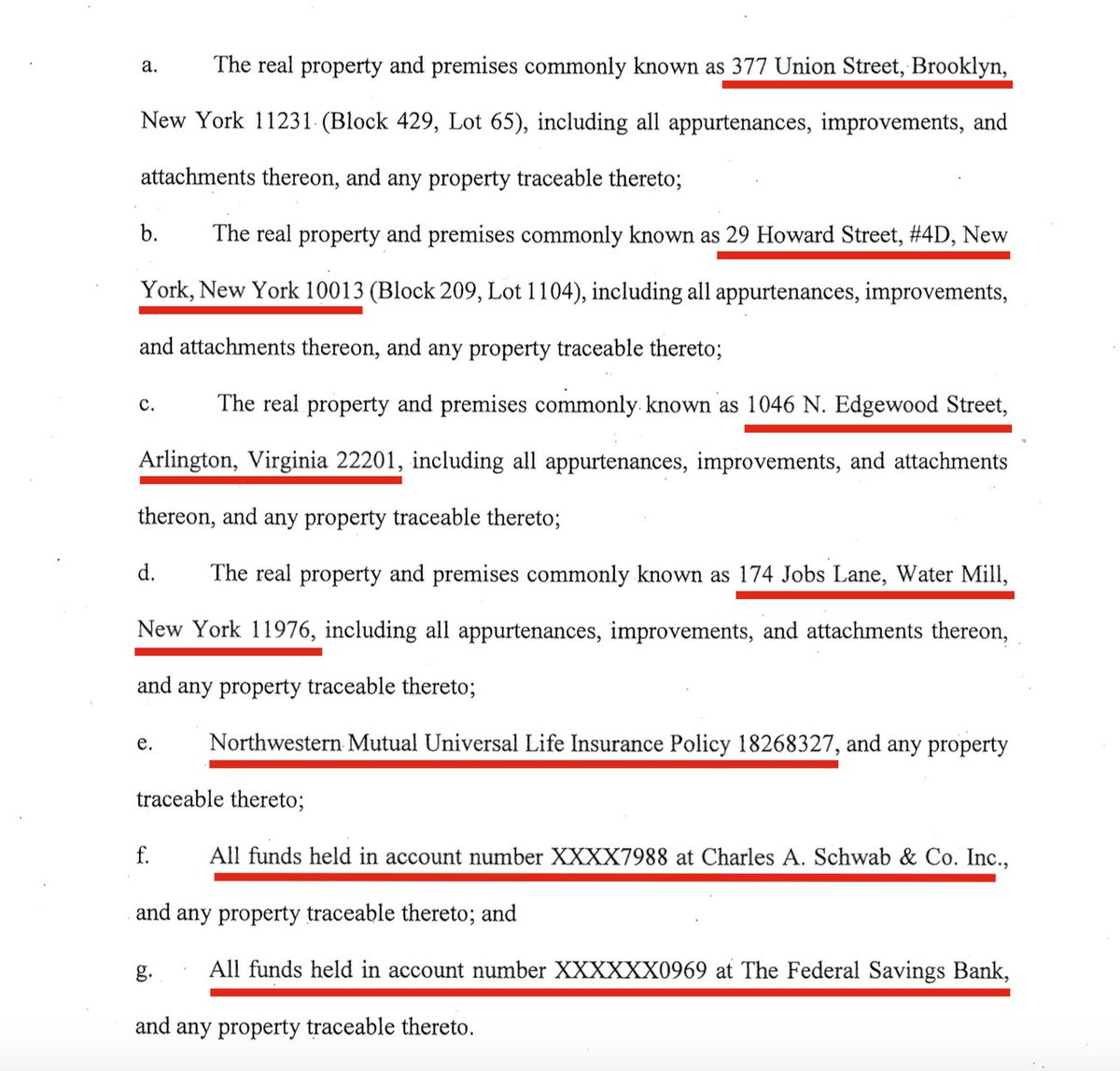

In 2009, Yanukovych declared his candidacy for president in the following year’s elections. Manafort beefed up the operation running out of his Kiev office, and Kilimnik began playing a bigger part, orchestrating key campaign logistics in a way that transcended his initial role as translator and interpreter.

Throughout the Yanukovych campaigns, the operative said, “There was no secret that [Kilimnik] had been in the intelligence services back in the Soviet Union. He would talk about it. Others on the campaign — Paul, Phil Griffin, Rick Gates — they were pretty open about his background.” But the operative added, “The view was that they were all in the Soviet Union at one point in time, and now they’re Ukrainian and they’re trying to get something going in their own country.”

When Yanukovych finally won the presidency in 2010, he shelved his promises about adopting a more open, pro-Western government. He moved to exert increased control over the media, as well as the legislative and judicial branches of government, the latter of which prosecuted, convicted and jailed his vanquished 2010 election rival. He backed away from a commitment to the European Union, and moved closer to Russia, eventually accepting a $15-billion aid package from the Kremlin.

Some on Manafort’s team began raising concerns about Kilimnik’s background in the Russian military and rumored affiliation with the country’s intelligence service.

Griffin, who did not respond to a request for comment, had been serving as Manafort’s deputy, but he left the team for another consulting gig in 2011. Kilimnik assumed many of his duties, taking charge of Manafort’s Kiev office and running the operation while Manafort was out of the country, which was much of the time, according to people who worked with and around Manafort’s firm.

Unrest was spreading in Ukraine as activists alleged rampant corruption and plundering by Yanukovych’s regime and demanded closer ties with Europe, while Russia sought to exert more control.

But Manafort continued working for the Party of Regions, and he and Kilimnik continued traveling the country together. The pair flew aboard a private jet to Crimea for a day in mid-2013, according to Ukrainian border control records and a flight manifest.

The Party of Regions paid Manafort’s firm millions of dollars a year, multiple sources said.

Ukraine’s anti-corruption agency obtained documents showing that from 2007 through 2012, Yanukovych’s party had earmarked $12.7 million in off-books cash payments for Manafort, The New York Times revealed this week.

Manafort, who’s been criticized by some former colleagues for prioritizing cash over principles, rejected the report. He asserted in a statement that “the suggestion that I accepted cash payments is unfounded, silly, and nonsensical.”

The statement stressed that in his domestic and overseas campaign work, “all of the political payments directed to me were for my entire political team: campaign staff (local and international), polling and research, election integrity and television advertising.”

**

Yanukovych’s reign came to an abrupt end in early 2014, when widespread protests over corruption and a demand for more integration with Europe prompted him to step down and flee to Russia under Putin’s protection.

But Yanukovych’s exile wasn’t the end for Manafort and Kilimnik. They began working for Opposition Bloc, which won some seats in Parliament during an October 2014 election.

Manafort this week issued a statement declaring that his “work in Ukraine ceased following the country’s parliamentary elections in October 2014.” But his trips to Ukraine continued, according to entry data reviewed by POLITICO and interviews with people who worked with or around Manafort in the country; Manafort traveled to Kiev several times after that election, all the way through late 2015. And one Russian-language media report indicated that he offered advice to Opposition Bloc politicians in late 2015.

Asked about the report and whether his travels to Ukraine last year contradicted his claim that he ceased working in Ukraine after the 2014 elections, Manafort told POLITICO via text message: “I had no contract and did no business after 2014 elections.”

He did not respond to questions about his relationship with Kilimnik, the unpaid bills from Opposition Bloc or whether his protégé’s background was a cause for concern.

The Trump campaign did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Opposition Bloc.

Ukrainian political insiders say that Kilimnik did continue working for Opposition Bloc after the 2014 parliamentary elections.

Kilimnik has represented Opposition Bloc in meetings with international diplomats, according to several people in the international business and diplomat community in Kiev, where Kilimnik is regarded as an important liaison both to Opposition Bloc and to an influential oligarch who is playing a leading role in the party. “From 2013, he was the face of the organization here,” said one operative in Kiev.

At some point, Opposition Bloc had stopped paying what it had owed Manafort’s firm, according to people familiar with the situation. They said that the party still owes Manafort’s company a significant amount of money.

One person with direct knowledge of the unpaid bills wouldn’t say how much was owed to Manafort, but said, “It’s an amount you would definitely want it in your bank account.” Another person who has discussed the unpaid bills with people close to Manafort said the amount was in the “millions” of dollars.

When the party stopped paying its bills, Manafort’s Kiev office, which was being run by Kilimnik, began running late on its rent and employees’ salaries, according to several people familiar with the situation.

“They didn’t pay the Ukrainian office. They didn’t pay rent or salary for people,” said a person who worked in the office.

Another former team member said “KK is averse to conflict, so when the money wasn’t coming in, he just went dark and that pissed a lot of people off.” The former team member recalled that when Manafort traveled to Kiev in 2015 to try to secure the cash he was owed, he was “ambushed” in the lobby of the city’s Hyatt hotel by the landlord for his office demanding back rent.

Some U.S. foreign policy types see Kilimnik as a reasonable representative of an oligarch who can be reasoned with, and they discount talk about his ties to Russian intelligence.

“I always understood that he was in the Russian Army intelligence for a couple years,” said an international political consultant, who has worked with Kilimnik, and who stressed that, at the time, all Russian men were required to serve in the military. But the consultant added, “I don’t think it was as big a deal as people made it out to be.”

Bill Browder, an American-born investor whose business in Russia led to him being blacklisted by Putin’s regime as a national security threat, differed. “It’s not like you can say, 'I used to work for [Russian intelligence].' It’s a permanent affiliation. There is no such thing as a former [Russian intelligence] officer.”

David Stern, Bryan Bender, Michael Crowley, Josh Gerstein and Nahal Toosi contributed to this report.

CORRECTION: This article was updated to correct a reference to Rinat Akhmetov, who is Ukrainian, not Russian.

https://www.politico.com/story/2016/08/ ... nik-227181